With the upgrading of some of the country’s most popular resthouses (like the Tissawewa Resthouse at Anuradhapura becoming The Grand, the Ambepussa Resthouse becoming Heritage Rest and the Tissamaharama Resthouse being transformed into a hotel) I have been looking at the history of resthouses in Sri Lanka.

As places for travellers to rest for the night, they were developed by the British colonial administration by extending the network for travelling officials begun by the Dutch. Resthouses were usually built in superb locations, each within a day’s horse ride from one another.

|

| A picture from the past: Anuradhapura Rest House |

While resthouses now are government or local authority properties, according to Sir James Emerson Tenant writing in his book “Ceylon” of his stay at resthouses in 1845 and 1846, they were “constructed by private liberality along all the highways and forest roads.”

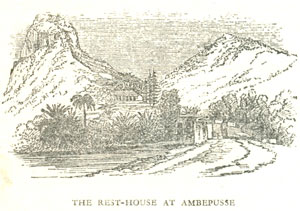

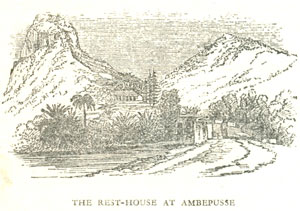

Tenant was particularly impressed with “the picturesque resthouse of Ambepussa,” although he warned of the “treacherously beautiful spot” in which it is located as having “acquired a bad renown from the attractions of the scenery and the pestilent fevers by which the locality is infested.”

The resthouse at Ambepussa is the oldest purpose-built resthouse still in use today. It was constructed during the building (1820-1831) of the road to Kandy under the direction of Captain Dawson, for whom a monument commemorating his “science and skill” in planning the road still towers over Kadugannawa.

The oldest building used as a resthouse today is the Tangalle Resthouse, converted from a Dutch administrator’s residence. Set in stone at the foot of its entrance steps, is the date of its foundation as 1774.

As recently as 60 years ago, resthouses were governed by a strict set of rules. The handbook of the Automobile Association of Ceylon for 1950 decrees “No bed, sofa or couch in the resthouse shall be used for the purpose of sleeping unless a sheet is spread thereon.” The AA used to grade resthouses according to a star system and included notes, such as “meals cannot be obtained without previous warning. Shooting: elephant, deer, leopard, etc.”

|

| A stout traveller sleeping in a broken down planter’s chair : A photograph in Henry W. Cave’s book , “Golden Tips”. |

The AA handbook listed 110 resthouses while the 1986 Ceylon Tourist Board booklet “Accommodation Guide of Resthouses” featured 133 resthouses but omitted some of the most popular today, like Ambepussa and Tissamaharama. Since then of course, many resthouses have closed while others, like the one at Bentota, have become hotels.

The standard of accommodation in a resthouse was variable. In 1929, Clare Rettie, writing in “Things Seen In Ceylon,” was worried by bats, rats and rat snakes in the ceiling of her room. She wrote that resthouses “are usually clean, though by no means luxurious, and the vagaries of the native Resthouse Keeper frequently prove amusing.”

Even in 1974, the author of Handbook for the Ceylon Traveller, thought of advising travellers: “Technically, resthouses supply meals and linen. But in the majority it is tempting providence to hope for a meal without due notice, and foolhardy to count on spotless napery or unragged bed linen.”

The indefatigable reporter of life in Ceylon, Henry W. Cave, recorded in his book “Golden Tips” in 1900, “The resthouses are fully furnished with chairs, tables and beds. We notice that the cane or rush seats are usually in a state of disrepair; but we make the most of such trifling circumstances.” He illustrates his point by including a photograph of a stout traveller sleeping in a planter’s chair where the webbing has collapsed.

There is an illustration in The Graphic, published in England on May 17 1890, about the resthouse experience in this country 120 years ago. The illustrator has named his hero Dr Syntax after the character created by the popular British cartoonist Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827).

With the caption “Dr Syntax in Ceylon” the full page cartoon starts with “Dr Syntax on his journey” riding a sprightly horse. He arrives at an unoccupied and defiantly closed resthouse and, climbing over the padlocked gate “he effects an entrance.”

|

| A sketch of the picturesque setting of

the Ambepussa Resthouse |

He discovers the caretaker sleeping on the floor and kicks him awake so he can “see to his steed.” While the doctor reclines in a planter’s chair complete with extended arms, “mine host” appears looking suitable obsequious. Next there is a sketch of the furniture being dusted and of servants tripping over a pig while chasing chickens. This has the caption “Dinner is preparing.”

Dr Syntax “orders a bath” and watches anxiously while water is poured by a servant from a jar into a wooden bathtub. There is no sketch of him having dinner but one of him in a nightgown and nightcap opening the door to “nocturnal visitors” - cows trying to get into his room.

The final sketches show the doctor, complete with knee high gaiters and frock coat, scrutinising the bill with obvious outrage, while the resthouse keeper, dressed in starched collar, jacket and sarong, claps his hands apprehensively. Then we see the doctor “recording his experience” and, watched by the keeper and groom, trotting off on his horse to continue his journey.

Resthouses may have changed in the past 120 years, but they are still ideally suited for the traveller wanting somewhere simple to stay. |