Crisscrossing Sri Lanka from Colombo to Trincomalee, Kandy to Hambantota, Badulla to Kinniya, Dr. Ronit Ricci, armed with a camera, is on a quest. It is a quest that takes her not only into the parlours but also to the backrooms and nooks and crannies of homes in search of the elusive written word which turns back the pages of time.

This scholar now teaching in Australia is “targeting” the written word of none other community than the Malays of Sri Lanka who number not more than 50-60,000.

The quest began in October 2009, when 44-year-old Dr. Ricci secured a fellowship from the American Institute of Sri Lankan Studies to turn the spotlight on Malay writing in Sri Lanka. Later, this year, she won a grant from the British Library’s Endangered Archive Programme to survey and document books, poetry, texts with charts or diagrams, all written in any form of Sri Lankan Malay.

|

| Dr. Ricci: On a quest. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara |

“Some of them may be written in Gundul/Arabic script, others may be Romanized Malay or Malay written using the Tamil or Sinhala scripts,” says Dr. Ricci who is a Lecturer at the School of Culture, History and Language, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra.

The ultimate objective is to preserve these fragile and endangered documents which have a high cultural value, the Sunday Times understands. The Endangered Archive Programme offers a number of grants every year to individual researchers world-wide to locate vulnerable archival collections, to arrange their transfer wherever possible to a suitable local archival home and to deliver copies into the international research domain via the British Library, it is learnt.

With the spread of Islam from west to east, Arabic infiltrated the cultures of the east, with people who became Moslem utilizing the Arabic script. So Dr. Ricci began by looking at different kinds of writing and texts in Javanese, Malay and Tamil and thinking about how stories contributed to the conservation of Moslem culture over the centuries. The next obvious question was how do such stories get translated?

It was when Dr. Ricci was researching Muslim literature in South and Southeast Asia in Chennai, South India, for six months and Yogyakarta, Indonesia for one year in 2002-03 that she came across the fact that there were Malays in Sri Lanka, whetting her curiosity about their language.

However, she had to rein in that yearning until she completed her research and her findings in the form of a book, ‘Islam Translated’ in April 2011, the “result of many years of dedicated work” was published by the University of Chicago.

There were also other matters on her mind before she could finally venture out to Sri Lanka for she had a young family back home in Australia -- three children, two sons and a daughter, ranging in age from 13 to 5 years.

By this time she had also read two pioneering books on the Malays of Sri Lanka including the well-known ‘Lost Cousins’ by Dr. B.A. Hussainmiya.

Dipping into history, Dr. Ricci reveals the “fascinating story” of how the Malays came to Sri Lanka.

“The early Malays were banished to Ceylon as political exiles by the Dutch,” she says, explaining that although they were also sent to islands closer to their homeland, Ceylon was a prime destination. They were a diverse group, members of the royal family and important people in their respective societies, from Java, Madura, Sulewesi, Bali, Sumatra and Batavia.

They probably spoke different languages depending on where they came from. “There was no single common language. So Malay came to occupy the role of a lingua franca,” she says.

It was later that soldiers and servants arrived not only from Dutch-occupied Indonesia but also Malaya governed by the British, serving as the ‘Malay Regiment’ in the colonial army and when disbanded going into the Fire Brigade and the Police.

So by the time Dr. Ricci completed her doctorate, she was “very excited” because on her mind were the Sri Lankan Malays. Dr. Hussainmiya, very kindly, showed her the path, giving her names and phone numbers, from which she developed a contact base in Sri Lanka and slowly and surely got into the Malay community network.

|

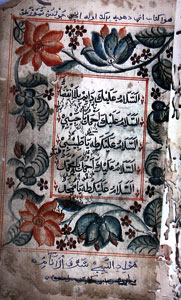

| Kitab Maulud Sharaf al-Anam, 1891– Arabic with interlinear Malay translation. (Courtesy of Thaliph and Jayarine Iyne) |

With her focus on the contents of old books and how they had weathered the lengthy circulation of time, she had to find yellowed, dust-covered and dog-eared material.

During her recent visit to Sri Lanka, she met many people, travelling far and wide to conduct an initial survey of what still survives and document every letter, book, manuscript, journal, deed et al in Malay.

“Some people have private collections, others have a single book handed down by their grandparents and treasured as a family heirloom while the National Archives has a collection on microfilm,” she says.

Sometimes her hunt for material didn’t yield results but people were always very gracious, welcoming a stranger into their midst and thinking long and hard and putting her in touch with a distant uncle or cousin whom they thought might have a document.

During her forays into Malay homes, not only did they allow her to photograph whatever material they had, they also gathered around her and took photos with her. Their hospitality was amazing, spreading sumptuous meals before her, she says, as she savours the “dodol” which has left a lingering taste. “Well fed, I am,” she smiles.

Getting back to Malay language material some of which is “invaluable”, Dr. Ricci reveals that stories or Hikayat were used as the Malay genre of narration in the early period of Islam. The stories were translated and adapted in Malay, according to this scholar. Poetry in the form of Pantun booklets was popular in Sri Lanka and she has unearthed printed copies from the 1920s.

She talks of “interlinear translations” in which every Arabic line is followed by a word-for-word translation into Malay appearing beneath it. This was necessary as when practising Islam, the Malays would have read Arabic but could not always understand the language. They, however, kept repeating their prayers in Arabic as it was sacred and the sanctity of the language had to be preserved.

Understanding of Arabic would have come with repetition and study and interlinear translations would have been used to pass on the knowledge of Arabic and likely as a model for teaching, she points out.

There are books from the collection of Baba Ounus Saldin who -- way back in 1869–launched ‘Alamat Lankapuri’, the first Malay newspaper in the world in Sri Lanka.

Yes, Dr. Ricci did see some of the books passed down by Saldin to his descendants. She is grateful that Thaliph and Jayarine Sukanti Iyne welcomed her with open arms into their home in Colombo to show her these books inherited from him.

She had also been able to capture on camera some handwritten material from homes in Colombo and Trincomalee with much potential from hill-country areas like Kandy and Badulla.

Hambantota and Kirinde where she went on whistle-stop tours yielded no written or printed material, only an oral tradition. “There is no evident remembrance of the written word there,” she says.

As she heads home to Australia with many photographs, what next for Dr. Ricci?

Once she comes up with a list of surviving material, the next stage would be to take digital photographs and set up a digital archive with open access on the British Library website.

Many people who may have valuable material may be inclined to destroy them due to the effects of humidity and insect-infestation. They may discard these materials not understanding their value because they cannot read them, says Dr. Ricci, explaining that her objective is to preserve what is still left, with the collaboration of the Director of the Sri Lankan National Archives, Dr. Saroja Wettasinghe, who is her counterpart on this project.

“We’ll keep a master copy at my university and put it online to preserve for posterity these documents from the past. This will not only help foster Sri Lankan Malay culture and language but also be available to scholars for further study,” she says.

Dr. Ricci will be back next year, hopefully having secured a bit more funding from the British Library to buy a sophisticated digital camera to continue the next phase of her project.

By March 2012, Dr. Ricci will know whether she has accomplished the first part of her mission successfully and is eligible to launch the second and final round.

Have you got any info?

Dr. Ronit Ricci is urgently requesting anyone who has information relevant to Malay writing in Sri Lanka (using any script type) to please contact her on ronit.ricci@anu.edu.au or Ms. Tinaz Amit on phone 0777067921 or teen102angel@yahoo.com |