![]()

It took almost ten hours to reach Madhu Road from Colombo counting of course, the flat tyre on one bus and a checkpoint at Anuradhapura. With two Army soldiers escorting each bus the peace pilgrimage progressed through Vavuniya without a hitch and on to the Mannar road. After the initial few kilometres, the scenery transformed into thick jungles cleared a couple of metres on either side of this recently captured road, now under Army control right upto Mannar, is protected on its northern side by deep trenches and barbed wire fences interspersed by bunkers overlooking the jungles beyond.

It was 5 o clock on Friday evening when we reached the Army check point at Madhu Road. The check point, on that day, was manned by more troops than usual, awaiting the arrival of our group. As the six bus loads tumbled out, baggage and all, daylight was already fading. In a bombed out shack, which was once a petrol shed, the army personnel searched and cleared the 300 people, priests and Catholic nuns who were among the pilgrims.

The Madhu shrine, centuries old and worshipped reverently by Catholics, is seven miles ( approx. 12 kilometres) away from this point. The turn-off would take us through jungle area into 'uncleared' land, which meant that the church was in an area out of army control. Therefore restrictions were imposed on the travellers. We were informed earlier not to carry batteries ( therefore no torches, cameras), candles.

At the check point, the Army restricted the amount of money and medicine going into Madhu. Rs. 200 was allowed per person. Any extra money had to be left with the army to be returned on our way back. Medicines were also limited. Not more than a card of Panadol was allowed.

"Even if you don't give it to them, the Tigers might take the money and medicine from you," the Army explained.

One young woman soldier boarded the bus to check our passes issued by the Army, before we finally left. "I wish I could come with you in civil clothes," she said wistfully. So close to Madhu Church she, a Catholic, had never got an opportunity to visit the shrine. "Please bring me some sacred soil from the Church," she requested one of our crowd.

Half hidden in the scrub, was a faded signboard. It was the Wildlife Department declaration of the Madhu Road Sanctuary and "no shooting was allowed". Several bullet marks punctuated the wording.

By now, it was around 7.30 p.m.and darkness shrouded the scrub jungles that surrounded the area. Everyone was happy to be finally so close to Madhu, but again, wary and some a little frightened of the LTTE checkpoint ahead. When the buses stopped, a breathless hush went through the crowd. Some tried to peer through the windows to catch a glimpse of the Tigers. Others nervously asked them to stay put. Several young men, in dark trousers and white shirt, boarded the bus. "Ayubowan" they said, smiling at the crowd. In halting Sinhala they tried to converse with us. Those pilgrims who could speak Tamil conversed with them.

All were requested to disembark and each identity card was checked with the list of names. One young cadre, in fluent Sinhala was enjoying a hearty chat with a group of girls. The entire clearing process was videoed by the LTTE, a generator mounted on a truck providing the necessary light.

In an old, roofless building, we were served tea and chocolate biscuits by girls in pleated black skirts and white blouses. Afterwards we had to walk to the buses once more and finally drove in to Madhu Church. Our watches read 9 p.m.

But at Madhu it was only 8.30 pm. Here, the recent time changes never caused a ripple since the people didn't adhere to them. At Madhu the old time, half an hour behind our own time, is still used.

Even at that late hour the reception overwhelmed us. Hundreds of children, bare foot thronged us as we got out of the buses. Coming from the refugee camp at Madhu which is within the church compound, these children were totally inquisitive of us, they wanted to hold our hands, touch our clothes... Some had learnt enough Sinhala to ask our names. Some were content just to stand apart and stare, turning away shyly when we smiled at them. A nun at Madhu who was with the children said, "Some of them have never seen a Sinhalese person and they were so curious to see you."

The next day was the first Saturday of October. Traditionally the Feast of the Holy Rosary is celebrated in this church on such a day. After a lapse of many years, the church was holding this feast with a large crowd of Sinhalese in attendance.

High

mass held at 7am, Madhu time, was in both languages, Sinhala and Tamil,

celebrated by the Bishop of Mannar, Dr. Rayappu Joseph and the Bishop of

Ratnapura Dr. Malcolm Ranjith. In an introduction, Fr. Devaraja, former

Administrator of Madhu church and now, head of SEDEC ( Socio Economic

Development Centre) said, "The holy church of Madhu has traditionally been

a meeting point between the Sinhalese and Tamils from all over the country."

High

mass held at 7am, Madhu time, was in both languages, Sinhala and Tamil,

celebrated by the Bishop of Mannar, Dr. Rayappu Joseph and the Bishop of

Ratnapura Dr. Malcolm Ranjith. In an introduction, Fr. Devaraja, former

Administrator of Madhu church and now, head of SEDEC ( Socio Economic

Development Centre) said, "The holy church of Madhu has traditionally been

a meeting point between the Sinhalese and Tamils from all over the country."

He said this peace pilgrimage had two main aims. One, obviously to pray to Our Lady of Madhu to bring peace to the country. The second was to initiate contact between people of the south and the thousands of refugees living in camps around the church.

The sermons focused on the need to bring peace to the country and an end to the war. Shortly after the mass was concluded, rain slashed the arid ground. For the people here, living in this parched dusty scrub, the rain was indeed a blessing. For many months Madhu area had not seen rain and faced a problem with water supply.

Later

that evening all 300 of us boarded the buses again, making our way down the

Palampiddi road to a second refuge camp, which accommodates the spill over from

Madhu camp. Here, at Thachinamadu about 3km north of Madhu 6000 refugees were

huddled into huts provided by UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for

Refugees). Again the welcome was stupendous. People, hundreds of children

amongst them, poured out from these huts running towards the buses.

Later

that evening all 300 of us boarded the buses again, making our way down the

Palampiddi road to a second refuge camp, which accommodates the spill over from

Madhu camp. Here, at Thachinamadu about 3km north of Madhu 6000 refugees were

huddled into huts provided by UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for

Refugees). Again the welcome was stupendous. People, hundreds of children

amongst them, poured out from these huts running towards the buses.

We were all led into a large hall, built of tree stumps with a thatched roof. On the earthen floor, a plastic sheet was laid out for us to sit. An LTTE political cadre, a retired government servant who identified himself as 'George' spoke to the crowd on the conditions at the refugee camp and invited more people from the south to come and bear witness to the hardships of the Tamil people living in the Wanni.

The LTTE once again began to serve us tea. As trays of biscuits were brought in by the girls, one pilgrim stood up in protest. "How can we eat your biscuits?," Marie Silva, an Ayurveda doctor from Nelundeniya said, her voice faltering with emotion. "Please take these biscuits and give them to your children. We can't look at their hungry faces and eat."

After discussing it over with George, Bishop Malcolm Ranjith asked the crowd to accept the biscuits but break them into two and give half to the children who were peeping into the hall, some even on trees. We all obliged willingly. Some even passed around their cups of tea.

The success of the mission to establish contact between the north and the south, the Sinhalese pilgrims and the Tamil refugees became obvious during this meeting. The sympathy evoked among the group at the plight of the refugees was not to die a natural death after the dusty Madhu roads were long behind us. Several pilgrims spoke up that afternoon, pledging support to the church's mission for peace. "We cannot close our eyes to this situation. We have an obligation to go back and tell others of the ravages of war, and the need to seek a peaceful solution," one said. Another pleaded with the LTTE to spread the message of peace among their ranks and look towards an equitable solution."You can see the suffering of your own people. Let us all renounce war." The suggestion was applauded by all the visitors.

Freddie Gamage from Negombo said that he with several others was exploring ways to send the refugee children school exercise books. All the visitors felt inadequate. We all wanted to do so much. But there was no money with us. We could not bring rations on the pilgrimage.

It was decided to collect whatever money we could spare to buy school books for the children at mass the next day. The visitors also generously gave their pillows, sheets, plates, clothes, and food to the church to be distributed to the refugees.

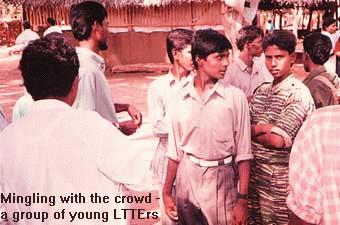

We

were escorted to the refugee camp and back by LTTE cadre. Young boys, mostly

unarmed and in civil clothing rode motorcycles, alongside our buses. A

Tiger-run truck too accompanied the crowd. One uniformed and armed cadre was

walking around close to the church canteen when we asked him if we could take a

photograph. With a violent shake of his head, this young Tiger jumped on his

motor bike and rode off. Women cadre, in their neatly plaited hair tucked into

Tiger striped caps, made an appearance that evening. They acted more aloof,

unfriendly when compared to the men. Sherine Perera, a pilgrim, asked one girl

if she could see her cyanide capsule, which she obliged. But their eyes never

smiled. "We will fight to the death,"one said, when asked if they

would agree to peace. LTTE cadre in civils mingled with us, often requesting

photographs and addresses of the Sinhalese.

We

were escorted to the refugee camp and back by LTTE cadre. Young boys, mostly

unarmed and in civil clothing rode motorcycles, alongside our buses. A

Tiger-run truck too accompanied the crowd. One uniformed and armed cadre was

walking around close to the church canteen when we asked him if we could take a

photograph. With a violent shake of his head, this young Tiger jumped on his

motor bike and rode off. Women cadre, in their neatly plaited hair tucked into

Tiger striped caps, made an appearance that evening. They acted more aloof,

unfriendly when compared to the men. Sherine Perera, a pilgrim, asked one girl

if she could see her cyanide capsule, which she obliged. But their eyes never

smiled. "We will fight to the death,"one said, when asked if they

would agree to peace. LTTE cadre in civils mingled with us, often requesting

photographs and addresses of the Sinhalese.

Rajan is twenty years old. He had joined the LTTE when he was just fourteen, and was already a hardened cadre. But to our lodgings he came in sarong and shirt and squatted there talking to the people in Sinhala. He did not look like a fighter. He was stunted and thin and said he could not reveal where they lived. His friend, a fifteen year old Tiger recruit was also talking to some Sinhala visitors. But the boy obviously felt uncomfortable with the line of questioning, and calling Rajan, quickly fled into the jungles in a kerosene-run motor bike. The LTTE ran a bus service which transported people from villages around to Madhu for the festive mass.

The vehicles sported a registration alien to us. "It is Prabhakaran's registration number," an elderly refugee explained to us in Sinhala and laughed with us. But a cadre who overheard the conversation, quickly reprimanded the man, old enough to be his grandfather, simply because he could not understand any of the exchange except 'Prabhakaran' and the humour that followed.

"This war is creating a generation of warped human beings" the Bishop of Mannar said. "These refugee children, some were even born in the camps. So many soldiers are disabled. The future mothers, so many young women are also in the ranks. The future of the country indeed looks bleak." The next morning a Sinhala mass was held especially for the pilgrims, but it was attended by a number of refugees also. Even as we knelt before the alter and offered prayers for peace, sounds of artillery shelling could be heard at a distance. All through the night our sleep was disturbed by these 'thud' noises in the distance. Later we found out that it was the Army defending their post at Puliyankulam.

Before we left, the LTTE escorted the buses to the Madhu school. Here we were asked to sit down on the benches arranged for us. Armed cadre roamed the area but none were hostile. In fact, here they served all 300 of us with a breakfast of a fried potato roll, murukku and plantain. Some confusion was apparent about the arrangements here. When I asked an English speaking cadre what the delay was, he replied, "We are expecting a high ranking leader to address you. But he will get late. Until then we don't have orders to let you people go."

But the leader never came and at around 10 a.m we were allowed to proceed out of Madhu. Outside church premises, once more we were checked by the cadre. This time our baggage was randomly searched while their video camera captured it all on film.

Back at Madhu road, the Army was awaiting our return. Baggage and bodies were carefully checked and the money confiscated earlier returned. The soldiers were all ears for stories of 'the other side?' They too had a story to tell. Apparently, while the LTTE was all preoccupied with the visitors from the south, around 200 refugees from Madhu had taken the opportunity to flee their control. On the evening of October 4, while we were at Thachinamadu camp, these refugees with bag and baggage had trekked the jungle and come to Mannar road waving white flags at the Army patrol. For these 200 people, our pilgrimage of peace became their ticket to freedom- not so much from the grip of the Tigers as from the pangs of hunger. We, unknowingly afforded them the chance of starting a new life, probably poor, but able to hold up their heads in dignity.

The Madhu Church has a long history. More so, the statue that is so fervently worshipped at Madhu. History has it that the statue of Mary, carrying the Baby Jesus was first found in a church in Mantai, six miles from Mannar.When the Dutch conquered the area and persecuted Catholics, a group of people escaped into the Wanni jungles with the statue. They ended in Marathamadu, deep in the jungles and occupied a customs house owned by the Kandyan king. The year was 1670. They were later joined by a group of some 700 Catholics from Jaffna peninsula. Among these was the daughter of a Portugese captain named Helena who, it is said, built the first church to hold the statue at this very spot.

Continue to Plus page 2 - Book Review

![]()

| HOME PAGE | FRONT PAGE | EDITORIAL/OPINION | NEWS / COMMENT | BUSINESS

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to

info@suntimes.is.lk or to

webmaster@infolabs.is.lk