|

15th November 1998 |

Front Page| |

Buddhism: ancient links with CambodiaBy Dr. Hema Goonatilake. (The writer is Senior Advisor to The Buddhist Institute Cambodia)Trade and marriage alliances strengthened religious ties between Sri Lanka and countries in South East Asia in ancient times. Kings of Burma and Cambodia were especially eager to marry Sri Lankan princesses. It was then a prestige symbol to marry a princess from Sri Lanka, the Holy Land of Theravada Buddhism. The Sinhalese chronicles record that Parakramabahu the 1st maintained close links with countries in the region. The Sinhalese envoys at the Burmese court were maintained by the Burmese king while the Burmese envoys in Sri Lanka received similar treatment. Sinhalese chronicles also mention that Parakramabahu the 1st had close relations with the Cambodian kings, Dharanindravarman the 2nd and Yasovarman the 2nd. Parakramabahu sent a princess for marriage to a Cambodian prince whose name is not mentioned. This princess was seized on the way by the King of Burma. (The land routes from Sri Lanka to the South East Asian region were always through Burma.)

They together formed a Sinhala sect in Burma which later spread to Siam and Cambodia. According to Burmese sources, Tamalinda did not return to Cambodia, but died in Burma. During the same period, there appears to have been a special residential quarter for Cambodians in Polonnaruwa, referred to as 'Kamboja vasala' (gateway to a Cambodian street) in the inscriptions of Nissankamalla. Nissankamalla has been identified by Prof. Mendis Rohanadeera as a prince from Singburi near Lopburi (present day Thailand) which was then under the Cambodian empire. Potgulvehera at Polonnaruwa and the fortress of Yapahuwa seem to have been influenced by Cambodian architecture. Sri Lankan monks as Dhamma teachersBy the 13th century, Sri Lankan monks were held in high esteem as Dhamma teachers and propagators. They introduced monastic education to Cambodia. They were also the religious advisers to the Cambodian royalty. They led the royal mission that introduced Buddhism to the neighbouring country, Laos. This trend continued in the later centuries. By that time, Pali had become the lingua franca of the region. The use of Pali words in Sanskrit inscriptions as well as the appearance of inscriptions written in Pali and Khmer show the growth of the Sri Lankan form of Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia by the beginning of the fourteenth century. The first inscription, written partly in Pali, and partly in Khmer appeared in 1306. A 15th century Khmer-Pali inscription specifically refers to a Sinhala monk by the name of Lanka .... Sri Yasa who taught the dhamma to Cambodian princes. Lanka Vihara

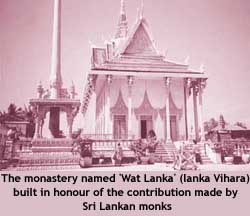

The king also built special kutis for the resident Sri Lanka monks who conducted seminars and discussions on the Dhamma. Later, when their activities became more established, the monastery was named 'Wat Lanka' (Lanka Vihara) in honour of the contribution made by Sri Lankan monks. Since the monastery was heavily damaged during the Pol Pot regime, it was renovated under the sponsorship of King Sihanouk's wife Kosamet, and was called 'Wat Kosamet'. But the Cambodians continued to call it 'Wat Lanka'; so its name was changed back to the original. These interactions continued even up to more recent times. In the 19th century, Sangharaja Pan of Cambodia sent a Buddhist mission to the Sangharaja of Sri Lanka, and received in turn relics of the Buddha and Ananda Thera. The chetiya in Phnom Penh, the capital city that enshrined these relics remains up to now the place where important Buddhist festivals, such as Vesak are celebrated. After several decades, an effort has been made in recent years to revive religious and cultural ties between the two countries. Since 1996, three Sri Lankan Buddhist monks have been teaching Pali and Sanskrit at the Buddhist University and the Buddhist High School. Recent historyThe Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot ruled the country from 1975 to 1979, during which over a million people were killed, many wats (temples) were destroyed. Buddhist texts were burnt or lost. Buddhist monks were killed, or expelled from the wats and were forced to do manual labour. It has been estimated that 50,000 monks (in 1969, 65,062 monks lived in 3,369wats) were either killed, or died of disease or starvation. Only after the Vietnam-backed Communist government took over in January 1979, were steps taken to reinstate Buddhism and Islam. An initial ordination was carried out with the assistance of a delegation from the Theravada Buddhist community in South Vietnam. The present Sangharaja has been in office since then. Buddhism was again made the state religion of the country. Present status of BuddhismToday 46,384 monks live in 3,467 temples. Since up to 1989, only those over 50 years of age were allowed to be ordained, monks today are either in their sixties and seventies or are the young ones who were ordained after 1989. Only a small number of monks are sufficiently proficient in Buddhist learning. Presently, the Ministry of Religious Affairs runs a teaching programme for Buddhist monks through its Buddhist high schools in the main cities and Buddhist elementary schools at provincial and district levels. The Buddhist Institute, the first centre of higher learning and research in Cambodia established in 1921 has recently launched a programme to assist the Ministry of Religious Affairs in revitalising Buddhist education in Cambodia, including the introduction of modern methods of teaching Pali. There are two monastic Orders in Cambodia - Mahanikay and Dhammayutnikay, with more than 90 per cent of monks belonging to the former. The latter was introduced in 1864 from Thailand, and was adopted by royalty and the aristocratic class. It gained prestige due to its adoption by royal and aristocratic families, but its adherents were confined geographically to the Phnom Penh area. A remarkable feature is that wats perform a significant social function. Wats in towns provide free shelter to monks and lay male students and to poor workers from far corners in the country. If not for the wats, these students would not be able to afford a higher education in universities and senior secondary schools that are available only in towns. In rural areas, it is usual for villagers to rush to the wat, in case of personal tragedies. Almost all wats in towns and villages serve as places of refuge to many elderly men and women who have no children to take care of them, or even when their children are married and settled down. These men and women serve the monks by cleaning the wat premises, cooking for the monks and doing such activities. As in other present day Theravada countries, women in Cambodia have no place in the Buddhist hierarchy. Many older women, leaving household life, shave their heads and dress in white robes and live in huts in monastery complexes and observe the eight or ten precepts. They are known as the Donchees. The vast majority of them are widows.. There are a few who have taken to robes at a younger age. A programme was launched last year under the patronage of the Queen of Cambodia to organise the Donchees scattered throughout the country into a Federation of Donchee Associations. |

||

|

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

|

|

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to |

|

In

retaliation to this, Parakramabahu carried out a raid on some of the ports

of Burma. Parakramabahu's victory in this invasion of Burma is referred

to in the Devanagala inscription off Mavanella. Before this event, the

Burmese King Alaungsithu (1112-1167 A.C.), a contemporary of Parakramabahu

the 1st (1110-1153 A.C.) had visited Sri Lanka and married a daughter of

a Sinhalese king, according to Burmese chronicles. The reign of Jayavarman

VII (1181-1215 A.C.) was the most illustrious period of Buddhism in Cambodia.

During this time the Mahayana deities were worshipped along with the practice

of Saivism. Although he was a Mahayana Buddhist who identified himself

with Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara as reflected in religious monuments such

as the Bayon, Tamalinda who is surmised to be his son went to Sri Lanka

to study Buddhism. Tamalinda was one of the four Buddhist monks who excelled

in the study of Tripitaka, among those who went to Burma with Chappata,

a Burmese Buddhist monk.

In

retaliation to this, Parakramabahu carried out a raid on some of the ports

of Burma. Parakramabahu's victory in this invasion of Burma is referred

to in the Devanagala inscription off Mavanella. Before this event, the

Burmese King Alaungsithu (1112-1167 A.C.), a contemporary of Parakramabahu

the 1st (1110-1153 A.C.) had visited Sri Lanka and married a daughter of

a Sinhalese king, according to Burmese chronicles. The reign of Jayavarman

VII (1181-1215 A.C.) was the most illustrious period of Buddhism in Cambodia.

During this time the Mahayana deities were worshipped along with the practice

of Saivism. Although he was a Mahayana Buddhist who identified himself

with Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara as reflected in religious monuments such

as the Bayon, Tamalinda who is surmised to be his son went to Sri Lanka

to study Buddhism. Tamalinda was one of the four Buddhist monks who excelled

in the study of Tripitaka, among those who went to Burma with Chappata,

a Burmese Buddhist monk.  The

first centre of Theravada studies in Cambodia was initiated by Sri Lankan

monks in 1422. This monastery was one of the five oldest monasteries in

Phnom Penh, founded by King Ponhea Yat who moved the capital from Angkor

to Phnom Penh. The principal library of Buddhist teachings in Cambodia

was housed in this monastery under the guidance of Sri Lankan monks.

The

first centre of Theravada studies in Cambodia was initiated by Sri Lankan

monks in 1422. This monastery was one of the five oldest monasteries in

Phnom Penh, founded by King Ponhea Yat who moved the capital from Angkor

to Phnom Penh. The principal library of Buddhist teachings in Cambodia

was housed in this monastery under the guidance of Sri Lankan monks.