10th October 1999

Front Page|

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business|

Sports | Sports

Plus| Mirror Magazine

![]()

Contents

- Taking pot luck?

- Can't do things overnight

- Puppies in search of owners

- Breathtaking romp with Moliere

- Why not to miss Knots

- Lighting a candle for Lylie

- Vasantha will not let you down

- Roll call 40 years on

- Another reunion

- Watte, watte everywhere…

- Booming billions

- Ananda made him and he made Ananda

- Three parts bitter…

- 'We are addressing it'

- A heart to heal

- AIDS is a problem

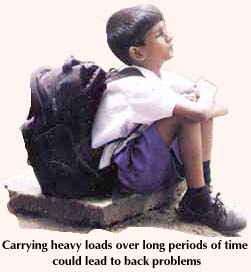

- Oh so heavy!

- Gone is the green

- For fruit project

- Honouring this mighty man

- Creating her woman

- Letters to the editor

Taking pot luck?

Do the educational reforms introduced this year meet the aspirations of the students? Kumudini Hettiarachchi reports

Ten months into the much vaunted education reforms. What is the situation in our schools today? Have the reforms worked towards bettering the lot of the students or increased the frustration among all — the students, parents and teachers? Will the reforms, with their ambitious plans for activity rooms, spotting the latent talents of the students early and making them work with the resources available in the area, create a bigger gap between the "good" schools and the schools with little or no facilities?

Yes, that is the fear among the principals, teachers, students and parents in the remote areas. And the fears seemed justified, when we heard their views, while on information-gathering trips far out of Colombo recently. We visited schools and spoke to people, not only in the Puttalam and Polonnaruwa districts, which lack many facilities, but also in the far corners of the Colombo district.

"Will Royal College produce masons and carpenters, under these reforms and my school doctors and computer specialists?" asked a Principal serving in the Puttalam district, taking me on a tour of the school premises. As I looked at the facilities, or in reality the lack of them, I had to concede that the prospect of this poor school producing a doctor or even a graduate was very remote. And the situation was more or less the same in many schools, except those located in the towns.

In Habarana, life is harsh, like in many parts of the country. The men, women and children survive through chena cultivations or cutting firewood, and selling these bundles at the roadside. In the nights, their homes are attacked by elephants. Life is difficult and many are the school drop-outs, as in the struggle for survival there is no time for lessons.

We spoke to the Principal of a remote mixed school with about 300 students. They have classes from Grade 1 to 11 and need 17 teachers, but have only 10 including the Principal. Who are the teachers they need? We knew the answer, before he replied. Yes, they didn't have teachers for maths, English, agriculture and art.

The non-facilities seemed like a long shopping list, which the school would never be able to get — no electricity, no library, there is what is called a "mini-lab" with practically nothing, the teachers don't have a staff room.

The students are expected to read newspapers and watch television to get an "amathara denuma" (extra knowledge), but they don't have any money to eat, so how can we tell them to buy a paper, the Principal said. There is no electricity and they study with the "kuppi lampuva" (bottle lamp), so how can they watch TV? he asks.

The conditions in the school are so pathetic that of the 18 students who sat the G.C.E. (Ordinary Level) examination last year, only two passed and were able to go onto their Advanced Level, which they have to do in another school.

He laughs when we ask about "vocational training". The idea is good and the area could be uplifted if small industries such as weaving, carpentry and masonry are taught and factories set up. The girls who drop-out of school could be taught cloth weaving, but it will be a long time before it sees the light of day.

Another Principal in a school with 1,200 children and classes from Grade 1 to 13 said they didn't have a science stream because there was no lab. There were 46 teachers on the staff. They haven't had a dancing teacher for four years. There was also no art teacher, so how could the children do their aesthetic studies?

With specific reference to the reforms, she said it was impossible to have activity rooms for the Grade 6 children, when the school lacked so many facilities, including basic requirements like toilets and water. For all 1,200 students there were just eight toilets, four for boys and four for girls. There was of course no water and the children had to draw water from the well in the schoolyard and cart it to the toilets.

The boys didn't have toilets, only urinals. The teachers too had only one lavatory. Most teachers who were transferred to the school were awaiting an opportunity to "flee" because they didn't have a chummery.

"There are about 48 children in each class and about three or four classes in one large hall," she said, as I closed my eyes and imagined one teacher shouting herself hoarse on English, another teaching maths and the third Sinhala. What kind of lessons would the children hear — a sentence of English, a little bit of maths and part of a Sinhala essay. The sum total being gibberish.

Of the 85 students, who sat for the OLs last year, less than half, 35, passed six or more subjects. Most of the others leave school and take to the selling of lotteries or "go behind tourists", the Principal said. All this is due to the lack of facilities. Those who get through the OLs have to seek AL lessons in other schools and only one student, who started her school career at this relatively "big" school, gained entry to university.

Every year, the intake to Grade 1 is 105 students, but in two or three years 10 to 15 drop out due to poverty. The demand for this and that, under the new reforms, which require children to undertake projects, will put off more parents from sending their little ones to Grade 1.

Many parents told The Sunday Times that schools were "unofficially" demanding money ranging from Rs. 10 to Rs. 200 from children to put up all the "work shelves", sinks and "display cupboards" which are an essential part of the education reforms. For parents of children attending schools in Colombo and other affluent schools, Rs. 10 may be "peanuts", but for families which don't know from where their next meal is coming every cent counts.

Having an equipped library in every school is a joke. "Lokka innawa, poth ne" (The big person is there, but there are no books), the Principal succinctly summed up the situation.

The scenario was similar in the Puttalam district. One school had 700 students and classes from Grade 1 to 11. The teacher requirement is 27 of which there are only 14 and understaffing is for the vital subjects of science, maths, art, Tamil, Sinhala and religion. English which needs three teachers, has only one for the whole school. The Principal said the school lacks all facilities. "Reforms are useless if the basic facilities are not there," seemed like an old record I was hearing all over again.

"Take Grade 1 for example. We have two classes with 31 students in each and for the construction of shelves etc. we need Rs. 50,000 for each, totalling Rs. 100,000. The government has allocated Rs. 60,000 and we are expected to find the balance Rs. 40,000."

How and from where? I asked.

"From parents and the school development society," he said. The school development society will also put pressure on the parents. A quick calculation and we came up with the amount of around Rs 645 that each of the students on an average would have to fork out.

The Principal stressed that they would never demand money from parents.

But we as parents know that, when a six-year-old child comes home and asks for money, no parent will refuse. Whether you are a millionaire or a pauper, a parent will beg, borrow or steal and somehow find the money for the child to take to class. And these parents in Puttalam were displaced people, who had fled the war-torn areas of the north and the east, leaving everything behind. They are attempting to put their lives together once again and ward off starvation by working the harsh soil or going out to sea.

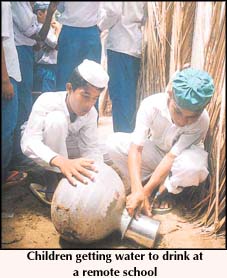

These

700 students have three toilets for the girls and three urinals for the

boys. They were worse off than those schools we visited in the Polonnaruwa

district. Though surrounded by the sea, they don't have drinking water.

The students troop to neighbouring compounds, some even quite far away,

draw water from wells, fill large heavy pots and lug them back to school.

These

700 students have three toilets for the girls and three urinals for the

boys. They were worse off than those schools we visited in the Polonnaruwa

district. Though surrounded by the sea, they don't have drinking water.

The students troop to neighbouring compounds, some even quite far away,

draw water from wells, fill large heavy pots and lug them back to school.

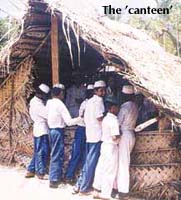

The library is a temporary building without a single book. It had a few newspapers and we did not dare look at the date. Even classrooms are in cadjan huts with their sides open to the wind and the rain. Of the 15 students who manage to struggle up to their OLs, only six barely pass.

What about the dreams of engaging students in various pursuits using the resources of the area? The agriculture plot would have made a person laugh, if it was not so tragic. A few students were attempting to dig the sandy soil, in the harsh noonday sun. I turned away without asking about water.

Of the requirement of two science teachers, the school had only one, while the other was on maternity leave. There was no substitute. The "mini-lab" equipment was a Bunsen burner and bottles filled with coloured liquid. There are sniggers around the office among the teachers when we discuss "equal opportunities" in education.

Moving away from education, we talk of sports. "Yes, we have a playground with absolutely nothing, only the land. That too is half a kilometre away," a teacher says. As we leave we stop at one hall — Grades 7A, 7B and 6A are having lessons. What a distraction. How do the students keep their eyes on the teacher in front of them, and concentrate when another is teaching a completely different subject a few yards away.

The last school we visit on that route has 892 students, and has classes from Grades 1 to 13. "Guru hingaya 17" (We lack 17 teachers), laments the Principal. They need four for English, but have only one. The same for science and maths.

He

explains the school classification to me. The criteria are whether it is

on a main road, has a post-office, bank, water line and electricity. He

mentions an affluent school in the district and says they've been classified

together, but stresses they are "athi dushkarai" (very remote).

"We don't have adequate buildings. There's no staff room."

He

explains the school classification to me. The criteria are whether it is

on a main road, has a post-office, bank, water line and electricity. He

mentions an affluent school in the district and says they've been classified

together, but stresses they are "athi dushkarai" (very remote).

"We don't have adequate buildings. There's no staff room."

English is the other sore point. The advantage that students of prestigious schools have over their village cousins, the reforms plan to overcome by introducing English as a form of communication to Grade 1 itself. Most Principals and teachers, while acknowledging the importance of the language, lamented that many Grade 1 teachers themselves needed indepth instruction. The idea seems to be good, but implementation has hit snags.

Another major problem that many parents complain about is the assessment of students. They fear that if the child does not curry favour with the teacher by taking presents, the assessment will be biased. "Can the future of my child lie in the hands of one teacher?" a furious parent asked. Numerous were the others who echoed his fears.

From our visits to schools and discussions with those involved in education, one thing becomes very clear. Though the reforms look good on paper, the facilities or their lack hinder implementation and would ultimately cause more frustration among the disadvantaged students, as the gap between them and those of prestigious schools widens. Maybe the first and foremost priority of the government, is to provide the basic facilities needed by these schools without taxing already poor parents to "help out".

With regard to English, the scrapping of which for political reasons was disastrous, maybe the older generation of teachers should be mobilised to train the younger ones who don't even know a word of it, and pass the OLs by applying the "tak, tik, tuk" method or answering the multiple choice questions.

The final analysis by all concerned is: Take a serious look at the educational reforms, in the face of such fears. Provide the basic facilities to all schools across the board, so that there will be a level education field not only for sons of the politician and professional, but also the poor farmer, fisherman and cinnamon peeler.

Can't do things overnight

Conceding that the inequities among schools, which have been existence long before the education reforms, cannot be "eliminated in a hurry", Director-General R.S. Medagama says that development of schools by division is underway.

"We cannot do it overnight, but 300 schools have been selected for development," Mr. Medagama who is in charge of the implementation of education reforms said, stressing that within the last three years Rs. 900 million had been earmarked to provide facilities.

The priority for education is two-pronged, he explained. "One was quality improvement through revision of curricula, training teachers to use the activity-based method, providing equipment and improvement of school management. The other was to provide equity and access to education for all children. Fourteen per cent of children who should be in school are out of education at present."

According to the Director-General, the 10,373 schools — of which 280 are "non-functioning" as they are in the war-torn north and east — are graded thus:

* Type 1 AB — schools where there is science Advanced Level. (there are 591 schools)

* Type 1 C — schools which have arts ALs. (1,888 schools)

* Type 2 — schools which have classes up to the OLs (3,674 schools)

* Type 3 — schools which have only primary classes (3,940 schools)

Mr. Medagama said that in 1994 there were 45 AGA divisions without a single 1 AB school. Children in those areas had to go to some other area to do science. Now schools in those areas were being upgraded.

With regard to the pressure put on children and parents by schools in the implementation of the reforms which stress on "activity-oriented" work and "learning by doing", he said the Ministry of Education was providing the funds, but there were problems in schools, where principals had demanded money from parents. "With the idea of encouraging practical work, activity rooms have to be set up for those in Grade 6. This has been implemented only in 200 schools and the ministry has provided funds to them," he assured.

Defending the school-based assessment (SBA), the Director-General said it was a "sound" education where children will be motivated to study from the beginning and not "cram" just before an examination. It will help parents know what their children are weak in and take remedial action. "There has been a fairly good response from teachers and parents."

The SBA is to regularise tests and assignments and the grades will be entered into a record book. But they won't have any bearing on the examinations. So if there is favouritism, the discrepancy in the exam marks and SBA grades will bring it out, he said.

Mr. Medagama stressed that there won't be "compulsory" streaming at the end of Grade 9, attempting to allay fears of parents and children that if one's father is a fisherman, the child may be forced to take to fishing, nullifying the concept of free education.

On the controversial topic of English, he said all students in the rural areas were very "weak" in the subject due to lack of usage. The poorest area was communication. They feared the language and that was why the Grade 1 teachers have been told to use about 200 words in class.

"Fifty to 60 per cent of the teachers can manage, but yes, 40% were weak. This was a problem which did not seem to have an answer. More training is required."

When asked about the dearth of teachers, Mr. Medagama said it was really a problem with "deployment". There are 188,000 teachers in the country and 4.1 million schoolchildren.

It works out to about one teacher for 21 students which was one of the highest teacher-student ratios in a developing country. Each year, 3,000 teachers pass out of the teacher training colleges and 750 graduates are recruited as teachers. "We have been liberal in our deployment, hereafter we should send new recruits to schools where there is a dearth, and adjust the system."

However, there is a shortage of teachers for main subjects like English and science. But they hope to train more on these subjects and overcome the problem. There was also a dearth of Tamil-medium teachers in the north-east and also the plantations. They hope to recruit about 4,000 over the next few years, he said.

Referring to ambitious plans to assist schools to greet the new millennium, he said around 75 schools including in places like Polonnaruwa and Moneragala have been provided with computer centres. The allocation for this was Rs. 100 million this year and Rs. 200 million next year. Another 1,000 secondary schools will have computer centres in the next three to four years.

More Plus

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports| Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to