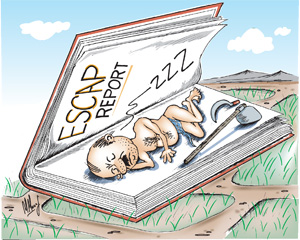

Inflation, public debt and agricultural neglectThe high rate of inflation, large public debt and the slow progress in agriculture are among three of the key areas highlighted in the Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific, Report for 2008. The UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far Eat (ESCAP) warned of rising inflationary pressures, the large public debt burden and slow progress in agriculture. These are three areas that this column has focused on often. Yet, as we have said before, advice on these falls on deaf ears. The ESCAP report is another warning of the dire consequences of these poor economic indicators.

The ESCAP Report points out that in Sri Lanka the inflationary pressures in 2007 led to an annual average increase in prices of 15.8 per cent, “substantially up from 10.0 per cent in 2006.” The current situation is much worse with inflation reaching 28 percent in March according to one index and 26 percent according to another. This is an unacceptably high rate of inflation indeed. ESCAP states that the main price pressures came from state-mandated hikes in fuel prices, supply shortages in domestic food crops due to poor weather and “sharply rising” demand-induced inflationary pressures. It appears to down play the role of high oil prices and of essential food imports. A tighter monetary policy by the government however raised concerns over the impact higher interest rates would have on the country’s public debt situation. The tight money policy adopted by the Central Bank may achieve its targets in controlling credit creation, yet the salient question is whether it would also cripple private industry. The ESCAP advises that “Sri Lanka needs to balance its concern with inflation against the rising cost of public debt servicing that has accompanied higher interest rates,” ESCAP Report states tactfully. It is also clear that even the attainment of the Central Bank’s monetary targets has not resulted in the weakening of inflationary pressures. In fact inflation is on the rise. A vital prerequisite for long term economic growth and sustainability of the growth momentum is the reduction of the debt servicing costs. It is therefore appropriate that the ESCAP report draws attention to the issue of rising public debt and its increasing debt servicing costs. It states that public debt remained “a serious problem” that needed to be addressed saying that “Excessive reliance on debt, whether domestic or external, carries macroeconomic risks that can hinder economic and social development. High domestic public debt pushes up interest rates and crowds out private investment, which is much needed to promote economic growth,” This in a nutshell is the dangerous consequences of the country’s rising public debt. The ESCAP Report noted that in 2006, public debt in Sri Lanka stood at 93 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), “as a result of the years of high fiscal deficits following the intensification of the civil conflict from the mid-1980s.” The latest “good” news is that public debt to GDP ratio has declined in 2007. This is due to the bloated GDP figure rather than a decrease in the debt as in fact public debt has risen significantly in 2007. A key to reducing the debt servicing costs is an increase in revenue. However it has to be a double-pronged strategy of also reducing expenditure. In as far as increasing government revenue is concerned there has been some progress. As ESCAP has noted: “The total revenue-to-GDP ratio in 2007 rose for the third consecutive year, benefiting from measures to broaden the tax base, rationalise tax rates and strengthen tax administration,”. Yet the country’s direct tax base is weak and subject to much tax evasion and avoidance. Although the government has announced its intent to bring down the deficit over the years this has proved unrealisable. The ESCAP Report notes that while there was a slight easing in the budget deficit, to 7.2 per cent of GDP from 8.1 per cent a year earlier, the figure “remains large.” According to ESCAP this is “partly because of Sri Lanka’s large public debt.” The government’s target is to bring the budget deficit down to seven per cent of GDP in 2008. The continuing increase in public expenditure exceeding increases in revenue collection may make this a pipe dream. In its Survey of Asia and the Pacific, ESCAP notes that public debt is a serious issue for Sri Lanka and South Asia. ESCAP warns that to avoid the threat of debt traps, Sri Lanka and other South Asian countries should pursue “vigorous macroeconomic policies to contain public debt, including domestic public debt before they become totally unmanageable.” This is a particularly significant warning that a government concerned about the future should take seriously. The third focus of the Report is on the revitalisation of agriculture that it considers a key to reducing poverty. ESCAP, in a wider view of the Asia Pacific region, said efforts to reduce poverty especially in the rural areas required the promotion of productivity in the agriculture as the rural poor account for some 70 per cent of the poor in the Asia-Pacific region. In Sri Lanka too poverty reduction in rural areas has been inadequate. While urban poverty has been halved between 1990 and 2005, rural poverty reduction has been modest. Twenty three percent of the rural population was deemed poor in 2005, compared to only 8 percent in urban areas. The report remarks that: “Agriculture appears to be neglected, even though it still provides jobs for 60 per cent of the working population and generates about a quarter of the region’s gross domestic product”. It points out that growth and productivity in the agricultural sector have slowed down. “In South Asia, growth in agriculture dropped from 3.6 per cent in the 1980s to three per cent in 2002-2003,” ESCAP noted. During the period 1990 to 2005 agricultural growth in Sri Lanka was only 1.5 percent. ESCAP argues that by raising the average agricultural productivity across the region some 218 million, a third of the region’s poor, could be taken out of poverty. It also noted that “large gains in poverty are also possible through comprehensive liberalisation of global agricultural trade, which could lift a further 48 million people out of poverty in the region.” Increases in agricultural productivity could raise incomes of Sri Lankan farmers and make a significant contribution to the reduction of poverty in rural areas and reduce urban rural income differentials. The ESCAP Report contends that the policy focus needs to be on revitalising agriculture. It requires connecting the poor to markets through improvements to rural infrastructure, the availability and management of water, agricultural technology, increasing the capacity to adapt technologies, and speeding up diversification and commercialisation. Besides this, it contends that improving land distribution and access to credit and extension are also important, as well as making macroeconomic policy “friendlier to agriculture, all enabling the poor to make a dent on poverty by themselves.” These lessons are very applicable to Sri Lanka, where the extravagant rhetoric for the improvement of agriculture has not been backed by action. Agriculture has been inadequately funded; poor rural infrastructure remains an obstacle to effective marketing and institutional credit and extension inadequate and ineffective. The control of inflation by reducing the public debt servicing costs is the most important policy change for ensuring greater stability in the value of the currency and fostering growth. Agriculture can contribute towards economic growth only if it is adequately funded and rural infrastructure developed. |

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |