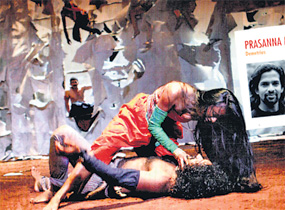

A dynamic unity from a babble of tongues"... for theatrical excitement and fresh insight, this vivid Indian Dream, first seen in New Delhi and subsequently at Stratford last summer, strikes me as being in a class of its own. There is a constant feeling of Shakespeare being minted anew, of a company of superbly committed, versatile and highly individual performers getting straight to the heart of the play without having to plough through accreted layers of tradition. Everything seems fresh, spontaneous and positively throbbing with sensuality." I was at the Sydney Theatre at the end of March to celebrate the appearance by the Sri Lankan actor Prasanna Mahagamage at this principal performance space in my city. Mahagamage, a product of the Somalatha Subasinghe school of theatre in Colombo gave an energetic and attractive south Asian style performance, as Demetrius in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in the Sinhala language.

Hs mother tongue worked in so seamlessly with the different ones of all his other Indian cousins that as the play moved on I got a feeling that all the Indo –Sri Lankan languages interflow in harmony. Interestingly this included the so called separate Dravidian ones, Malayalam and Tamil, in this multi language production which used English as well. The story in the Book of Genesis about God’s dispersal of people from the single Tower of Babel, into a thousand different confounding languages came to mind when experiencing this Indo- British creation, but for opposite reasons. There is no confusion here in the dispersed languages brought together to talk to each other. It would almost seem that the scribe of Genesis had forgotten that an all-knowing God would surely have known that bodies can communicate too, in a universal language. Because the action and plot were propelled forward by the non verbal, things coming out of the mouth became physical elements too. The huge success of the performance was also due to the adroit fusion of realistic acting (what the Indians call Lokadharmi) with dance theatre (what the Indians call Natyadharmi) At the beginning of the play the wealthy Tamil- speaking Egeus insists that his daughter Hermia marry the Sinhala- speaking Demetrius. But Hermia is in love with the Bangla -speaking Lysander. So, the Tamil- speaking Egeus appeals to the Malayalam- speaking Duke Theseus to apply an ancient Athenian law forcing a daughter to marry the man of the parent’s choice. The number of languages in this Indo- Sri Lankan wondrous jungle, full of Vedda like fairies and Panchikawatte like mechanics and street vendors, increases to embrace, Hindi, Marathi and Sanskrit as well. From this artistic idea that treated the entire region as one, what registered with me strongly, but unexpectedly, as drama sometimes does, was something political. How much more significant is each entity in the region when seen collectively than the single entity separately. Mahagamage’s further theatre education I noted had been at the National School of Drama, New Delhi. India’s new cricket league may soon create the same effect, and the gradual post colonial return of the island towards its giant cultural parent for reasons both current and age old, also passed through my mind. Apart from Mahagamage, Archana Ramaswamy (also pictured above), doubling as Hippolita and Titania stood out in a cast that left little room for differentiation. Archana was the Natyasastra ideal of dancer and actor, where one form cannot be separated from the other; where dance cannot be identified as the principal vehicle, as in Barathanatayam, because here Lokadharmi blends in without being noticed, with Natyadharmi. As for languages, in Shakespeare’s own words these were all “accents yet unknown” to him. And certainly “states unborn” in their form today, were India and Sri Lanka at his time. And yet, his prophetic words, in Julius Caesar, though literally interpreted as referring to political assassination - “How many ages hence - can in retrospect be used to embrace with love, this highly imaginative germ of an idea of the British Council, the tremendous energy, great creative power and fine relationship with foreign cultures of Tim Supple its British Director and the collective artistic infusion of the Indian creative team got together by Supple.

In real life the arousal of the emotions can lead to active uncontrolled, unpredictable results. In the Elizabethan Shakespearean theatre, these same emotions were art- controlled to result in passive yet dynamic enjoyment. By what means? By the artistic intervention of music, poetry, song, stylized movement, dance all in the envelopment of a stage as simply an acting space and not as an illusion of a real place. On the evening when I experienced this production I had it confirmed that the Elizabethan Shakespearean theatre can meet its counterpart of India in natural union. The ancient Sanskrit theatre of India is physically discoverable now, only in the folk forms which carry some of its means and values, in some of the various classical dance forms, in the museum- like preserved Kuttiyattam of Kerala and in the sensual temple sculptures of Hindu India. But the complete theoretical basis of classical Indian drama is found in the Natyasastra of circa two centuries before the birth of Christ. And if you read it in translation today, you would sense it helps to understand Shakespeare’s Elizabethan theatre too, of about one thousand eight hundred years later, the Bard unknowing of the predecessor’s existence. The skills and techniques, as Sydney’s leading reviewer noted, are rare in Western theatre; they are very Indian in a hybrid of the folk and the classical Natyasastra. Particularly, the Sutra-like demonstrations of Kama by the various lovers in action. And yet, the meeting ground of Elizabethan Shakespearean and Natyasastra /folk Indian is the physical, musical and visual communication of theatre, which is the secret of this Indo- British creation. Predictably the now well blunted dart thrown at European directors of using Indian theatre as exotica was pointlessly aimed again by some Indian directors like Chetan Datar who ignored or was unaware of Elizabethan theatre techniques. As Indian critics pointed out , in the towering urban metropolises of India today, folk and traditional forms would seem as exotic as they would be in New York or Los Angeles This wonder of the theatre has already been seen by thousands of Indians, and has toured Britain, where in London it was the hottest ticket to get. It is on its way to France, Germany, the USA and Canada. It struck me in a lighter moment that the other Sinhala speaking performers who gift their precious mother language to crowds in other lands are the likes of Sangakkara, Jayasuriya and Malinga, and their charity begins at home. But even so the pearls they carry to distant grounds would only be a few urgent exhortations like “udabalapang”, “allapang” and “dhuwapang”. So, it was with disappointment I learnt that Prasanna Mahagamage would not be able, even to turn that old adage the other way around, and get the satisfaction that “Charity ends at home”. Costs, I was told would prevent it from coming to Sri Lanka. And that is the reason for this piece which is not in the form of a customary review. It is an appeal to Colombo’s business houses and the British Council to meet and talk. It is also a suggestion to the British Council that if all fails in finances they explore the possibilities of Ely Landau’s American Film Theatre method which has preserved so many classics, in the form of theatre, through the medium of film. This product can then be shown across Sri Lanka. |

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |