I set off from our quarters situated opposite the Tissamaharama Rest House on the road to Kataragama with the first light of dawn. The view from the bund of the Tissa tank early in the morning is unbelievable. On the right is the water spread of the tank. Darters and cormorants are already busy. Sometimes there are teal as well, both whistlers and cotton. Towards the end of the bund before the road descends to join the main road to Hambantota, a huge Mara trees spreads its branches over the water. Torque and langur monkeys are awake, some with newborn babies safe in their belly pockets.

On the left, downstream from the bund is the expanse of paddy fields irrigated by the tank. The shade of green varies with the age of the paddy. When the wind blows through the ripening stalks of golden grain, the sound is a song. If it is harvest time there is actual singing.

The most breathtaking sight is the pure white stupa of the Tissamaharama Vihara standing serenely amidst the glittering green. I stop for a few minutes midway on the bund and just gaze. Some days there is no other human being to be seen. The scene is soothing.

Next, the village of Pannegamuwa is reached in 15 or 20 minutes of riding through patches of paddy and little houses. Ellagala Anicut (diversion structure) built by the British across the Kirindi Oya is of elegant cut-stone masonry. It was routine to leave the bicycle just off the road and walk along the narrow three foot wide path to the gauge post on the bank of the river. The gauge reader lived at Pannegamuwa. Most days I went with him to check the readings recorded by him. Occasionally I went alone and read the gauge so that accuracy of readings submitted weekly to the office could be verified.

Periodically a colleague who was a good friend, came from the Hydrology Branch in Colombo to take river flow measurements. This involved taking cross sections of the river and measuring the velocity of flow. He came on his B S A 350cc motor cycle. I usually joined him to assist and immensely enjoyed the ride. At 70 mph it felt like flying!

After inspecting the gauge station, one returns to the main road and the bicycle. Breakfast at the gauge reader's was fresh boiled manioc with coconut and hot sambol followed by ginger tea. The village of Pahala Mattala was about 11/2 miles west of the main road. The repairs to the sluice of the tank was inspected to ensure progress. Returning to the main road it was about an hour's ride to Tanamalwila Rest House for a delicious lunch.

Sometime in 1954, we had to do a full investigation survey of an abandoned tank named Diulwewa, situated close to Tanamalwila between the main road and the right bank of the Kirindi Oya. It was a small tank that had been abandoned perhaps for 100 years, now completely overgrown. The tank bed area was full of woodapple trees which gave the tank its name.

The empty shells of the woodapple fruits excreted almost whole by elephants that fed on ripening fruit, lay everywhere. The survey took two or three days. We did not see or meet any elephants perhaps because the fruits were not ripe that time of year.From Tanamalwila, turning left westwards along the road to Hambegamuwa, the first village was Bodagama.

The village tank referred to in the DAC priority list as Bodagama Ara Maha Wewa was due for improvements. The little village of Anukkangala with 30 or 35 families was about 11/2 miles south of the road. I spent a night with the school master of Anukkangala before proceeding to Mahagal Wewa about seven miles away in the Malala Ara catchment. The school was a single long building. The school room occupied most of it. The teacher's living quarters was at the rear. A store room and kitchen was attached. The toilet was detached. The only teacher was principal as well.

As my visits were not notified in advance I had to be fortunate to have wild boar or venison for dinner. Otherwise, it was invariably dried fish, dhal and curry of chena vegetables or drumstick from the school garden. He was in his thirties, unmarried at the time and good company.

On one of these tours, an abandoned tank named Getakumbuk Wewa had to be surveyed. I came by car to Tanamalwila with three trained survey workers from Tissamaharama. The car was left at the RH. We walked to Anukkangala, about seven miles away carrying the instruments. It was holiday time for the schoolchildren. The friendly school master was kind enough to accommodate the workers in the school hall. I had a camp bed inside with a mosquito net. The school room had only half walls and there were plenty of mosquitoes. The workers protected themselves with a few bonfires around the building and burnt raw gliricidia leaves. The resulting smoke kept the mosquitos away! They covered themselves head to toe, with their sarongs and towels!

We awoke very early, packed some of the previous night's rice in banana leaf parcels and left soon after daybreak along the stream bed five to six feet wide, about three miles downstream from Anukkangala. It was the dry season in July/August. The tank had only a little water mainly used by animals. The stream bed was completely dry and formed the easiest access to reach the breached bund. Four men were hired from the village to clear the survey lines and assist the trained workers who handled the instruments.

The area was home to a herd of elephants about ten in number. The branches cut in clearing the survey lines were normally pushed onto the sides, so that there would be a clear view for the instruments. The elephants made it a habit of using the cleared lines and feeding on the cut branches. They fed either the previous evening after we had gone or early in the morning before we arrived. Sometimes, the village workers went in front shouting to chase away the elephants. Thereafter time was spent removing the branches from the survey lines. We were never troubled by these elephants probably because we made their food more easily gettable. Perhaps more grateful than some human beings who harm the hand that feeds them!

Presumably, this long abandoned tank would have been restored and people settled to cultivate fields converted from forest. I wonder what would have become of that herd of elephants.

From Anukkangala which was in the Kirindi Oya catchment area, it was a seven mile trek across the divide to the Malala Ara basin and my work site at Mahagal Wewa. This stretch was just a track used by honey gatherers and hunters from the village and animals of course. The bicycle was pushed most of the way due to the terrain and low overhanging branches. I was never in danger from the elephant, bear and leopard that were plentiful in this forest. I carried only a bread knife in my basket!

I spent a couple of days at Mahagal Wewa to assess the progress of work, measure completed work and enjoy faithful Aranolis's food. Often when the villagers knew that I was there someone would leave a beehive on my door step. Aranolis would squeeze, strain and convert it to honey. Fresh or dried wild meat was also provided free by anonymous donors.

From Mahagal Wewa it is four miles to Ihalakumbuk Wewa and another 11/2 miles to Pahalakumbuk Wewa on the road to Hambantota. A surveyor from Devinuwara was encamped here and if he was in camp invariably a night was spent with him. One day I reached his camp and found the surveyor and his workers away. Only the boy who functioned as his cook was in camp. The boy suggested that I stay to shoot some teal which he would prepare for lunch. To do so we had to walk stealthily around the tank, taking cover at the edge of the forest in order not to disturb to the teal. The boy carried his master's 12 bore shot gun. I had two No 04 cartridges in my pocket. It was necessary to get within 50 feet or so which meant wading in water.

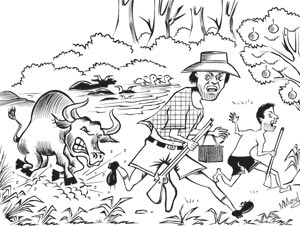

We came out of cover into the open bending low. A herd of village buffalo were wallowing. The teal were just beyond them. When we were about 100 feet away suddenly a wild buffalo which was with the herd came at us. We ran for our lives and I climbed the first tree at the forest edge which happened to be a woodapple tree and hence thorny. I reached a safe height of about 10 feet with the gun in my hand before looking for the boy and the buffalo. The boy himself had climbed another woodapple tree about 30 feet away. The buffalo stopped his charge about 25 feet from us. His majestic head and horns were a fearful sight. He pawed the ground angrily.

Regaining my breath in a few minutes, I wondered whether to use the bird shot but decided against it. In the meantime the boy who had both hands free threw some raw woodapple fruits at the buffalo! They fell short. The buffalo stood his ground for what loked like eternity and finally retreated to join the herd. With the buffalo's back turned the boy and I climbed down and fled back to camp. The whole episode had taken an hour and half. It was 12 noon. We were both hungry and lunched on a hot curry of dried sprats and long beans. Quite good but not as good as teal! Of course, very much better than being impaled on buffalo horn!

On another occasion I had reached Pahalakumbuk Wewa. It was very cloudy and began to rain by the time the surveyor's camp was reached. The rain intensified and became a torrential monsoon downpour. When there is such heavy rain after the ground is saturated and the tanks are already full or nearly full, the runoff is near 100%. The surveyor's camp itself was not inundated, but by nightfall it was water, water everywhere. When it was dark some villagers from Migahajandura came and informed us that the tank was overflowing and a breach was feared. It was not the surveyor's responsibility. But being the only government staff officer (apart from the school teacher or village hospital staff then known as ''apothecary'') connected with the land, they had come.

Since I was there, the villagers and I left to inspect Migahajandura tank bund, about a mile away. The rain continued. The surveyor very kindly lent me one of his men and a 5 cell torch. The road had turned into a river. We walked knee deep with some villagers in front, the surveyor's man just behind me with the torch to light the way. In the muddy water I stepped onto a ''log'' which quickly moved under my foot.

The "log" turned out to be a small crocodile. It was more frightened than I was, surfaced a little ahead and swam away! At Migahajandura, instructions were given to the Vel Vidane to breach the bund at the earmarked ''breaching section'' to prevent serious damage to the main bund by over topping. However, the rain eased off and the water receded is a few days.

When conditions were normal, I would return to Hambantota through Gonnoruwa and stay a night with a friend. Next morning, very early I began the journey back to Tissamaharama. I started off at Pallemalala, a village between Hambantota and the turn-off to Bundala, producing the best buffalo curd perhaps in the whole island. A large pot costing 25 cents could not be consumed even by a dozen adults! After Pallemalala it was ontoWeligatta, Wirawila, Debarawewa and back along the bund of Tissa tank to our quarters.

These journeys over a period of about 2½ years confirmed the need to improve living standards of the people with the least disturbance of the environment. The people were poor yet extraordinarily kind, courteous and hospitable, always ready to share what they had with a visitor. They lived in peace and harmony, amongst themselves and with nature. Human elephant conflicts were very, very rare.

Let us be all Sri Lankans. If we are prepared to share our mother land in a fair and reasonable way with all others and animals in the forest, then conflict would be avoided. The majority do not own this land. The concept of "giving" something to other communities is in my view totally incorrect. |