8th April 2001

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business|

Sports| Mirror Magazine

Different moods

The current group ex- hibition at the Havelock Place Gallery displays the work of three Sri Lankan artists - from Kelaniya University (who are now art teachers in their professional life) - and an Australian

artist with Sri Lankan roots.

Australian

artist with Sri Lankan roots.

Coming from Dehiattakandiya, in the north-east Lasantha Chandan Kumara grew up in a village where he developed his love for art. As a symbol of his work, the 'Atta Magala' (Kamath Chakkraya) or paddy threshing field, relates the artistry he sees inherent in everyday village life. Taking this 'folk' concept to the modern realm, Lasantha Kumara aims to bring about a better appreciation of his heritage.

Premanath Kottage has participated in several group exhibitions at the National Art Gallery in Colombo and has won awards for his work. His paintings are about politics and violence.

Sisira Kumara is intrigued by the human face. "I am using it as a basis for abstraction or as a 'jumping off place'.

"Expression manifests foremost in the face and including humanistic forms can speak to the audience," he says.

Australian-born with Sri Lankan and European roots Sam Carew-Reid has been surrounded by artists in his family. "All my work is based strictly on channelled energy from another source. I am merely a puppet on strings. My goal is for people to receive a healing of some sort each time they look at my work," he says.

The Exhibition will continue upto May 18, at The Havelock Place Gallery,

6 and 8 Havelock Place, Colombo 5.

Dance and verse move in poetic expression

This first book of po- ems, after which Khulsum Edirisinghe stopped writing poetry altogether, was written between the ages of 17 and 22. It is sensitive and exploratory reaching out to a whole range of experiences and emotions.

Two eminent educationists - her grandmother, Clara Motwani and her mother

Goolbai Gunasekera  were

part of her childhood. They were undoubtedly important influences in her

formative years.

were

part of her childhood. They were undoubtedly important influences in her

formative years.

College life in India was followed by the completion of graduate studies in English and Dance at the University of North Carolina in the United States. On her return Khulsum ran a Ballet School in Colombo. She married Janaka Edirisinghe when she was 20, and has two children, a daughter, Tahire aged 15 and a son, Rahul, aged nine. The Moonchild and Other Poems is dedicated to them.

Khulsum's involvement with the arts has given her a fertile base for the blossoming of her poetry.

Her voice is distinctly individual. Rhythms from both dance and verse move in her poetic expression.

The title poem The Moonchild is a surrealistic journey beginning with a calm and dreamy encounter.

"As the sun goes down

She rises to the occasion

With the moon.

She runs about, sylph-like

On a bleached sea-shore

To touch the silver upon the surface."

Now the choreography of the poem changes its tempo and characters.

"She rides high on the crest

Which laps her with its rabid tongue

with a lunatic frenzy.......

Startled canines howl like teething infants

At a distance................."

But the Moonchild does not stay to continue her adventure.

She "Flees the night"

A tinge of cynicism runs through the intellectual intent that pervades On Reading the Gospels, at Easter. Khulsum deplores the hollowness with which people celebrate this event:

"....................... If that was your intent to see

Wrong righted by regret

I can see why, after the first uneasy hours.

You rained the heavens to soothe their sores.................

But in forgetfulness we go about our days.

And easter eggs in mocha shells

Resuscitate the waning appetite of our day."

The language of the dance, wedded to the philosophy of understanding change between time past and time present, as in Improvisation.

"Let me

Recreate your ambience.

Forget the warmth you sit on.

Transport yourself on mercurial wings

To the corner of this room.

................. The mirror awards

A whitened state

Upon which we'll be free

To love until death"

The lyric, To Janaka portrays both the desolation of absence and the wholesomeness and fulfilment of togetherness:.

Now I know that a month can seem like a lifetime,

Two, eternity and three, beyond vision.

I also know now that revealing oneself

Can make you laugh with joy and cry with confusion.

Your acceptance of me, in spite of myself.

Is a flood of warmth and well being......"

Auditions with which Khulsum is so familiar as student dancer and teacher in the Ballet School she ran for eight years, is captured in a poem by that name.

It sums up the hopes and fears, nervousness and excitement that auditions offer to young hopefuls, waiting in line not knowing what their fate would be:

"When the jaded figures file in

Through the open door,

The invitation to dance is almost irresistible.

Warming up to it,

These serialized movers

Stand to face the wand

Of the fairy

Who will either cloak them in glory

Or not."

Khulsum has a gift for creating atmosphere and drawing the reader into the poem. and she does this so deftly in Come in from the Rain

"................. Crusty roaches play

Hopscotch on the terrazzo,

And the intermezzo

Plays on in house next door.................

Geckoes in skin - tights

Leave caudal delights

Squirming for hours

On the floor.

Night has fallen with the hailstones again.

And all the lurking fears

Have come in from the rain"

Khulsum, who presently heads the Department of Value Education at the Asian International School, has let her poetic sensibilities be fallow for a long season.

One sincerely hopes that with her talent, sensitivity and long exposure

to the study of dance, literature and philosophy, she will return to the

Muse whose poems await her.

Hobson-Jobson and all things Sri Lankan

Sustaining the British Empire in the Indian subcontinent took many forms.

The administrative training of recruits to the East India Company was one

of obvious importance. Another form - not so well understood but nevertheless

important - was the compilation of a lexicon of the thousands of  Anglo-Indian

words vital to communication and the furtherance of imperialism on the

subcontinent.

Anglo-Indian

words vital to communication and the furtherance of imperialism on the

subcontinent.

Twenty-odd works of this nature were published during the nineteenth century - including several from Ceylon - the majority of which covered words used in official correspondence. H. H. Wilson's Glossary of Judicial and Revenue Terms (London, 1855) became a standard work. However, by far the most comprehensive and useful to the typical British resident in India was the enigmatically titled Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive (London, 1886).

Hobson-Jobson was chiefly compiled by Colonel Henry Yule, a product of the East India Company's Military College at Addiscombe, Surrey. Although Yule's career as an engineer was mostly concerned with railways, bridges and irrigation canals, his special interest was in mediaeval travellers to the East, as is evinced in his Cathay and the Way Thither (1886). In the task of compiling Hobson-Jobson, Yule was assisted by A. C. Burnell, an eminent Indian scholar of the Madras Civil Service. As Yule was then living in Palermo, their extraordinary collaboration was carried out solely through correspondence.

Unfortunately Burnell died four years before the publication of the glossary, and so his contribution was truncated. Perhaps this is why many writers mention only Yule's name in connection with the compilation of Hobson-Jobson. Yet Yule acknowledged his co-compiler's input in the following words: "Burnell contributed so much of value, so much of the essential."

In his illuminating Introduction to Hobson-Jobson, Yule sketches the history of Anglo-Indian words in the English language and goes on to comment on the significant role that members of the East India Company played in the dispersion of such words.

"Words of Indian origin have been insinuating themselves into English ever since the end of the reign of Elizabeth and the beginning of that of King James, when such terms as calico, chintz, and gingham had already effected a lodgment in English warehouses and shops, and were lying in wait for entrance into English literature," he writes. "Such outlandish guests grew more frequent 120 years ago, when the numbers of Englishmen in the Indian services, civil and military, expanded with the great acquisition of dominion then made by the Company; and we meet them in vastly greater abundance now."

More than a century later, many of these "outlandish guests" - some examples being bangle, bungalow, catamaran, cheroot, curry, dinghy, guru, khaki, loot, mango, musk, pepper, pundit, pyjama, shampoo, sugar and thug - have become firmly ensconced in the English language worldwide. Yule remarks that this process began with the return of Anglo-Indians to the British Isles. They brought with them not only their Indian curios but language oddities as well, and were responsible for the propagation of such words in select social circles.

"This effect," Yule continues, "has been still more promoted by the currency of a vast mass of literature, of all qualities and for all ages, dealing with Indian subjects; as well as by the regular appearance, for many years past, of Indian correspondence in English newspapers, insomuch as that a considerable number of the expressions in question have not only become familiar in sound to English ears, but have become naturalised in the English language, and are meeting with ample recognition in the great dictionary edited by Dr. Murray at Oxford."

Yule's reference to James Murray, editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is noteworthy. Yule and Burnell commenced their labours in the mid-1870s, just a few years before Murray and the OED team commenced theirs. Indeed, the period from 1879, when the so-called 'big dictionary' project was resurrected under Murray's leadership, to 1886, when Hobson-Jobson was published, was one of direct overlap where the compilations were concerned. This was not merely a general overlap of time, but a specific overlap of word entries as well.

Furthermore, as the initial late nineteenth century users of Hobson-Jobson and the OED discovered, both works displayed a similar lexicographical approach, which differed to previous English dictionaries. This was exemplified by the employment of illustrative quotations to trace the history and usage of words. One obvious difference between them, however, is that the word entries in the former work - which in any case number only a few thousand - are generally more extensive than the hundreds of thousands of entries in the latter work. This is hardly surprising, though, since many Anglo-Indian words have convoluted derivations.

Due to the overlap of the two projects, Yule was in contact with Murray and the OED team regarding identical areas of research. The OED Archivist informs me that many letters written by Yule have been found so far during the current revision programme, which will eventually lead to the third edition of the dictionary. These letters cover a list of predominantly Anglo-Indian words, such as abada, agrum, ambarrah, amuck, amildar, araba, bablah, bamboo, banana, boabab, booty, caystock, chappow and china.

The communication between Yule and Murray lead to a common use of illustrative quotations in both works - a fact acknowledged by both parties. For instance, the Preface to the first fascicle of the OED states: "Colonel Yule was good enough to put at our disposal the proofs of his Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Terms, as it was passing through the press. Quotations thence supplied are marked (Y)." Then again in the 'Prefatory Note to Part II' (1885): "Colonel Yule has generously allowed us the use of his proofs of his Discursive Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Terms, an important work now in the press, which has often been of service in helping to complete the history of such of these words as fall within our province."

Yule, in his preface, writes of Murray in a similar, respectful manner: "The editor of the great English Dictionary has also been most kind and courteous in the interchange of communications, a circumstance which will account for a few cases in which the passages cited in both works are the same."

Like most researchers, I use the revised second edition of Hobson-Jobson published in 1903, 14 years after Yule's death. This was edited by William Crooke, who reveals in the preface that the eminent Ceylon scholar, Donald Ferguson, aided him. Although Ferguson is not as well known as other Ceylon-based British researchers of the period, he played an important role in the study of the Portuguese and Dutch periods of the island's history. Furthermore, he was a Sinhala scholar, described by the respected etymologist, W. W. Skeat, as being "intimately acquainted with Cingalese."

Not for these reasons alone was Ferguson ideally suited to assist Crooke. In addition he had already written a study titled Anglo-Indianisms, which appeared in the Ceylon Literary Register (Vol. 1 Nos. 28 & 29) of February 11 and 18, 1887. This was a general review of the first edition of Hobson-Jobson combined with a more specific commentary on the entries for words of Sinhala or other origin associated with the island.

"Those who have studied the pages of Hobson-Jobson have agreed in classing it as unique among similar works of reference, a volume which combines interest and amusement with instruction, in a manner which few other dictionaries, if any, have done," Crooke writes of the glossary. At the beginning of the twenty-first century Crooke's assessment still holds true. No doubt it was this uniqueness that lead to a reprint of the second edition of Hobson-Jobson in England in 1986, the year of its centenary, and the publication of a new edition in 1994. It was also reprinted in India during the 1990s and has spawned a recent pair of pale imitations, Sahibs, Nabobs and Boxwallahs (1991) and Hanklyn-Janklin (1992).

Hobson-Jobson, incidentally, was the peculiar phrase used by British soldiers in India to describe a "native festal entertainment," otherwise known as a tamasha. This Arabic word meaning 'going about looking for entertainment' is, of course, still very much in use on the Indian subcontinent, including Sri Lanka. What the compilers of the glossary do not reveal is that in nineteenth century Ceylon, Hobson-Jobson appears to have referred to a particular 'native' entertainment, for the Illustrated London News of June 11, 1870, states:

Hobson-Jobson is apparently the English nickname given at Colombo to a grotesque festival performance of the town sweeps exhibited at the Cinghalese feast of the New Year, which falls on April 11. It was, we are told, witnessed by the Prince (Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh) with considerable amusement."

The phrase Hobson-Jobson is an Anglo-Saxon version of the chants of "Ya Hasan! Ya Husayn!" made by Shi'a Muslims as they beat their breasts in the procession of Muharram, held during the first month of the Muslim lunar year. It is an excellent example of the ignorant and imitative manner in which a number of Anglo-Indian words were coined. Another such absurdity recorded in Hobson-Jobson is chopper-cot, which is the abuse of a genuine Hindi term, chhappar khat, meaning 'a bedstead with curtains.' Then there is Jungle-Terry, which is a mutilation of the Hindi Jangal-tardi, a name applied to 'a border-tract between Bengal and Behar.'

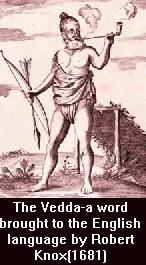

While the majority of words included in Hobson-Jobson are of Indian origin there is evidence of an Anglo-Sri Lankan sub-variety, as Ferguson recognised in 1887. Ferguson, however, does not comment on or list all of these words, so I have endeavoured to identify them. They are as follows:

Adigar, agar-agar, almyra, anaconda, anicut, areca, batta, Berberyn, beriberi, betel, bo-tree, boutique, Burgher, cabook, calamander, Candy, carambola, cat's-eye, Ceylon, Chilaw, coir, Colombo, comboy, corle, cornac, corral, dagoba, devil-bird, dewale, dissave, Dondera Head, Elu, gow, griffin, hackery, hoowa, hopper, horse-radish tree, ipecacuanha, Jafna, jaggery, jargon, Lunka, mamooty, mangelin, modelliar, muckna, musk-rat, Negombo, palmyra, Palmyra Point, pandaram, paranghee, peon, Point de Galle, poon, Putlam, rest-house, sarong, seer-fish, Serendib, Singalese, snake-stone, tailor-bird, talipot, tank, tic-polonga, toddy, tom-tom, Trincomalee, Veddas, vidana, vihara and wanderoo.

Of these 75 words, 52 are common to the second edition of the OED. Several others - adigar and dewale, for example - may be included in the third edition. There are a fair number of place names - 13 to be precise - for Yule justifies: "We judged that it would add to the interest of the work, were we to investigate and make out the pedigree of a variety of geographical names which are or have been in familiar use in books on the Indies."

Some of the words are of Sinhala origin and exclusively associated with the island, such as hoowa, dissave, and tic-polonga, while others, such as anicut, mangelin, and talipot are of sub-continental origin and associated with Sri Lanka and South India. Some words of Sinhala origin have found lodgment in distant lands, such as anaconda and beriberi, while others of distant origin, such as boutique and corral, have found lodgment in Sri Lanka. Of those words exclusively or closely associated with the island, only anaconda, beriberi, bo-tree, calamander, Veddas, and wanderoo have attained international usage during the twentieth century. This is reflected in their inclusion in both concise English and American English dictionaries.

The reviewer of Hobson-Jobson in the Economist of February 1, 1986 remarks that "It is a dictionary in which it is impossible merely to look up a word, since fascinating clutter keeps getting in the way."

This fascinating clutter includes my favourite curiosity, the gruesome sudden death, which was slang for a fowl served as the standing dish at a dawk-bungalow (resthouse). The bird, usually about a month old, was caught in the yard as the traveller entered and was cooked and on the table by the time he had bathed and dressed.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to