News/Comment|

Plus| Business| Sports|

Mirror Magazine

Crushing the revolt

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi and Renuka Sadanandan

April 5, 1971: Attack on Wellawaya Police Station at dawn, 5.20 a.m. But

what was planned at that secret meeting of the JVP high command at the

Vidyodaya University Sangaramaya on April 2 was not a dawn strike. Something

had gone wrong. The Wellawaya cadres, had literally, jumped the gun. All

police stations were to be attacked on the eve of April 5 and by that one

mistimed move, the JVP's plans to overthrow the government came undone.

But

what was planned at that secret meeting of the JVP high command at the

Vidyodaya University Sangaramaya on April 2 was not a dawn strike. Something

had gone wrong. The Wellawaya cadres, had literally, jumped the gun. All

police stations were to be attacked on the eve of April 5 and by that one

mistimed move, the JVP's plans to overthrow the government came undone.

Two policemen were killed in Wellawaya and the government moved swiftly to clamp a curfew.

A few hours later in far-away Kegalle, the radio room at the district Police headquarters was abuzz. As soon as Government Agent K.H.J. Wijedasa and Superintendent of Police Ana Seneviratne heard of the Wellawaya attack, they put into action their secret contingency plans. All petrol stations in the Kegalle district were sealed to conserve fuel and police guards deployed at water supply stations, electrical sub-stations and the telecom exchange.

But the JVPers were one step ahead. They felled trees across the power lines, plunging whole areas into darkness. Cycle chains were thrown over high tension wires to cause short-circuits. Phone lines were cut and roads blocked with uprooted trees and lamp posts.

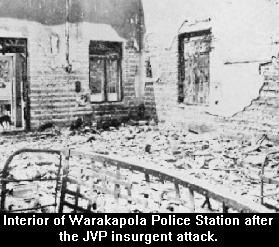

After the mistimed Wellawaya attack, Police stations around the country were placed on alert but in many instances they were ill-equipped to face the sudden onslaught. Justice A.C. Alles in his book, 'The JVP 1969-1989' details the mass-scale attacks. Overall, 92 police stations across the country were attacked and five, Deniyaya, Uragaha, Rajangane, Kataragama and Warakapola overrun by the insurgents and 43 abandoned by the police for "strategic reasons". Fifty-seven police stations were damaged.

Meanwhile in Kegalle, the situation was worsening. The GA's residency was adjoining a large forest reserve which the insurgents used as a hideout, and every evening, GA Wijedasa, his wife and their domestic help would take their dinner packets and stealthily walk across to the HQ, which by now was like a fortress. They would spend the night on the benches there.

"By midnight on April 5, there was a total blackout in the district. There was no transport, no communication, no vehicles on the roads, and no water. Kegalle was deserted," says Mr. Wijedasa.

Within the district, all 14 police stations had fallen. "There was minimal resistance by the Police. The cops just vanished." At the main police station, the police radio was their only link with the outside world.

Tholangamuwa Central College, located some five miles from Warakapola on the Kegalle road was the JVP headquarters. A bulldozer was parked across the entrance to the school so that no one could storm them.

For the officials at Kegalle, it had been like sitting on a powder keg. From January 1971, the signs had been evident. Information flowed in from two sources: Police intelligence and also the spy network floated by SP Seneviratne with the special vote of Rs. 50,000 he had. Reports were received of "various" things happening in the countryside.

Small groups of youth meeting in secret in lonely places. The 'desana paha' (five lectures) being delivered. Collection, manufacture and storage of weapons. Jungle training of fighting cadres. Testing of devices in the jungle. Shooting practice. Strange explosions.

"There were also reports brought in by grama sevakas, DROs and informants such as school principals of young boys going 'missing' from home for days. Tailors in the area told us how orders for a large number of uniforms had been placed," GA Wijedasa said.

"As a professional cop, I was able to interpret the signs and symptoms. Little incidents were brought to my notice. Six-foot lengths of barbed wire were being removed from fences. These were subsequently cut into 1-1 1/2" pieces and used in anti-personnel bombs," says SP Seneviratne.

JVP cadres were also collecting fused bulbs and jam bottles, tins and similar-sized containers to make bombs and Molotov cocktails. The containers were filled with kerosene or petrol and had a fuse. "That was what saved us. Kegalle is a wet area and they couldn't light the fuse, because the boxes of matches they carried were damp."

Often at night, when the SP and GA met for dinner in the Residency, they would hear the tell-tale 'clink-clink' of the insurgents making their way through the forest. They were carrying 'Molotov cocktails' in their haversacks and as they walked over the uneven terrain, stumbling over rocks and roots, the bottles and cans would knock against each other.

What would also give them away was the sound of the dogs barking. As they walked past a house, the 'game-ballo' would sound the alarm.

Early in 1971, as the unrest in Kegalle escalated, GA Wijedasa activated the District Security Coordinating Committee of which he was chairman. It comprised the SP, the head of any big army unit stationed in the area, the Additional Government Agent and the Headquarters DRO.

Information about the activity in the area was collated and analysed and many reports sent to the government. But nothing happened. Daily despatches were sent through special messengers. But no action was taken. Defence Secretary A.R Ratnavale put them to Premier Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who discussed the intelligence reports at her Cabinet meetings with MPs from the area. But they only reassured her that "our boys" wouldn't do such things. The matter was shelved. Many times.

The Kegalle officials also made recommendations that in case of a massive attack, schools should be converted to detention centres. They were not taken seriously until Nelundeniya.

In March 1971, came the massive blast at Nelundeniya. Five were killed and a 15'X20' pit dug into the kabok with many tunnels snaking it, stored with explosives was unearthed.

"It was an arms dump and quite a 'lead' into what was going on. Then only did the government open its eyes and send an army detachment to the area," GA Wijedasa says.

After a nightmare week of living in fear and tension, the GA sent his wife to the safety of the capital city. She travelled with the Kegalle VOG (Visiting Obstetrician and Gynaecologist), disguised as his servant, managing to escape the stringent JVP checks on all outbound vehicles.

The JVP couldn't hold on to the areas they had captured, including parts of Kegalle, because they lacked popular support, believes GA Wijedasa. "The people were not used to violence. They had last experienced violence and such atrocities only during the 1915 riots. They were not happy about the destruction of public property - buses and government buildings being set ablaze and the disruption of essential services. The JVP's contention that tea and rubber estates should be uprooted and manioc and sweet potato planted instead did not go down well with the common man. The thinking that big houses and bungalows had to be shared by five families was met with disapproval. This may have all been misdirected JVP propaganda or misinformation, but the people opposed that."

In his book "Sri Lanka - A Lost Revolution", author Rohan Gunaratne theorises that the JVP made some crucial errors. "They strongly believed that capturing State power can be done by attacking what they believed was the strongest weapon of the State - the police. The JVP activists believed that a police station in an area was the most powerful and respected machinery of the State.

"Further the JVP activists who managed to control large areas of the country following April 5 did not know the next step.

Politically they stopped after hoisting a red flag over a building they chose as their base and waited until the other areas were also captured instead of consolidating the power they had or marching to other areas with the public and taking over control of the neighbouring towns and cities.

They failed to enlist the support of other leftists and trade unionists. They failed at least in the areas they controlled to set up a new government or a new administration."

By the time that bloody April had ended, GA Wijedasa estimates 15,000 had been killed in Kegalle district. "There was not much burning of bodies, but they were thrown into the Maha Oya."

He backs up his contention from personal experience. In 1970, soon after assuming office as GA he had placed an advertisement to fill the 60 grama sevaka vacancies in the district. There were 740 applications. "Then the insurrection came and the recruitment had to be put on hold. The process was reactivated in July 1971 and letters sent to all 740 applicants. Two hundred letters came back to me with the postal stamp - 'mohu soya gatha nohaka'. They were either missing, killed, taken into custody or being rehabilitated. No one knew."

Kegalle had fallen and likewise some areas of the south. Batapola, Deniyaya and Amabalangoda were under the control of the 'kotang anduwa'. Young revolutionary Sunanda Deshapriya, the District Secretary for Badulla was retreating through the Walapone jungles. But after a starvation diet of murunga kola for days, the 150 cadres under his command began deserting.

Ultimately the group dwindled to 12. They had neither food, nor money. Some days they were lucky if they could dynamite fish. Bitten by leeches, they struggled on, until six decided to go back into the city, others on to Knuckles. Two were captured and killed and the remaining four, including Sunanda went back to Welimada. He travelled from there to Batapola, disguised as a mason.

In areas like Batapola, which they now controlled, the JVP had barricaded themselves with trees and lamp-posts. When he finally reached Batapola, very close to his home, his comrade Sanath, the only JVPer to possess a pistol, was in control.

Sentry points had been set up and big bungalows and walauwas commandeered. Some 300 shotguns had been stockpiled like firewood and a repeater shot-gun reserved for JVP leader Wijeweera, still in the Jaffna prison. The cadres got around on bicycles, with couriers going from one stronghold to another. Villagers were only allowed to leave their homes to find food.

The JVP held Batapola till April 23. Then the army with the help of villagers attacked their camp. Sunanda was arrested at a military checkpoint.

Sanath escaped to Sinharaja with about 100 other rebels. Ultimately he sought refuge in Hiniduma, but was shot dead by the army along with his bodyguards, over tea and biscuits. He had been betrayed by a comrade.

Along with the police station attacks, the JVP also failed in certain key plans. Author Gunaratne sums up, "Four important missions which were poorly planned and executed made a significant difference in their drive to capture State power. First, the attack on the Panagoda Army Camp, second, the plan to kill or abduct the Prime Minister and senior Government officials and third, the capture of Colombo and fourth, the rescue of Wijeweera from Jaffna prison. All four missions failed. The reason is clear. The JVP overestimated the strength and capability of the student sector which Wijeweera himself heavily relied on and had once proudly named 'the Red Guard'."

Says Wijedasa, "The revolution was mistimed, miscalculated and misdirected. It was a thoroughly amateurish, childish effort. There was no preparedness. Their organisation was weak. Moreover, they had insufficient fire-power."

In May and June that year, with the backbone of the uprising broken and only mopping up operations in progress, Prime Minster Sirimavo Bandaranaike appealed to the JVP youth to surrender. Thousands of young people came forward. Some 200 state officers were mobilised to question them and record their statements on 'pink' forms for those who had been arrested and 'blue' forms for those who had surrendered.

The Vidyodaya University at Kelaniya, where the insurrection had been hatched with such hope, was where the disillusioned rebels were brought for questioning. A Criminal Justice Commission comprising five judges of the Supreme Court, including Justice Alles was hurriedly set up, dispensing with the normal laws of evidence to deal with the heap of cases.

The human cost of the JVP insurrection was grave. Fifty-three Security Forces personnel had died and 323 were injured. Though the government gave the figure as 1,200 dead, it was estimated that some 8,000 -10,000 JVPers were killed. According to Wijeweera, 15,000 of his cadres had died and twice that number of civilians had lost their lives.

"It was a foolish dream. This insurrection was not cruel or ruthless. It was small and beautiful. Sundara gathiyak thibba," says Victor Ivan, alias 'Podi Athula'.

Sri Lanka's destiny changed forever after the JVP insurrection. The legacy of 1971 has been the politics of violence.

Why so many intelligent, educated youth were willing to risk their lives and take up arms to topple a democratically elected government is a festering question that needs an answer. The roots of the revolution clearly lay in the high level of unemployment, under-employment and caste deprivation that stifled the hopes and aspirations of the rural youth.

Has any successive government addressed these issues even 30 years after?

Or are we still sitting atop a latent volcano of frustration?

Where are the key players?

JVP

leader Rohana Wijeweera alias 'Mahaththaya' who also masterminded a second

insurrection in 1988-'89 was killed by the army on November 13, 1989.

JVP

leader Rohana Wijeweera alias 'Mahaththaya' who also masterminded a second

insurrection in 1988-'89 was killed by the army on November 13, 1989.

Politburo member Wijesena Vitharne alias 'Sanath', was shot dead by the Hiniduma Police in April 1971.

Politburo member K.T. Karunaratne alias 'Karu' now works in a private company.

Politburo member and military wing leader Athula Nimalasiri Jayasinghe alias 'Loku Athula' is a People's Alliance MP for the Gampaha district.

Politburo member Piyathileke Samararatne alias 'Machang' took over his family business and was stabbed to death over a land dispute in 1995.

Politburo member Sunanda Deshapriya alias 'Asoka' is a journalist.

The military wing's Victor Ivan alias 'Podi Athula' is also in journalism and is Editor of the Ravaya.

The brutal side

The 1971 insurrection had its share of brutal killings, both by the JVP and the security forces. Two stand out:

Dr Rex de Costa, a distinguished citizen of Deniyaya with a long record of social service to the people of the area was ruthlessly slain by the insurgents for helping the police to try and repel their attacks. He had not only tried to enlist the help of other planters in this predominantly tea-planting district but also tended to some wounded constables in his bungalow and kept government transmitters in his home. For this he had to die.

On April 9, when Deniyaya fell to the JVP with the police station being burnt down, the insurgents went to Dr. de Costa's home and shot him at point-blank range. His children were hiding in a servant's room and his wife escaped death because an insurgent remembered that she had done some social work in the area.

The other horrific killing was the murder of the Avurudu Kumari of Kataragama, Premawathie Manamperi by the Police. Suspected of JVP involvement, Manamperi, 22, was arrested on April 16 by Kataragama Police and taken to the nearby Army camp where she was allegedly raped.

A day after her arrest despite her anguished pleas, the young woman was stripped and made to walk nude along the main road, repeating the words "I have followed all five classes".

Two security forces personnel escorted her carrying sub-machine guns. After she had walked about 200 yards, she was shot. They left her for dead. Later on hearing she was still alive, she was shot again.

The man who was asked to dig a pit and bury her, reported twice that she was still alive and so she was shot again, this time in the head. Her tormentors were tried before the Supreme Court, convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to