24th June 2001

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business|

Sports| Mirror Magazine

- Crossing Barriers

- Under the moon, under the stars

- A brush with life-drawing

- I was once a griffin

- Community concern

- Appreciations

- Curbing the demon at home

- Every coin has two sides

- He loved to live, he loved to act

- A life dedicated to preaching Dhamma

- Pancreatic reverse action

- Prostate gland: a large issue

- Medical diary:

- Secrets of a good night's sleep

- Physician heal thyself

- Doctors - the endangered species!

- That perfect wedding memento

- Letters to the editor

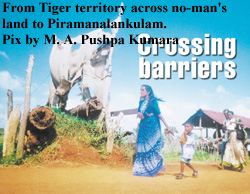

Crossing Barriers

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Music blaring from the vehicle speakers, we are bumping along the Vavuniya-Mannar Road. Every inch of the 26-seater Mitsubishi Rosa is packed, jam-packed really. Every tiny space including that which is meant for the legs has been stuffed with packages. A plastic can filled with kerosene, shapeless parcels wrapped with newspaper, a cycle tyre wedged between seats........and weary men, women

and children ready for a long haul.

women

and children ready for a long haul.

A baby screams and is hushed by its mother. The five-year-old next to me is wracked by a phlegmy cough. As a journalist, a seat had been 'reserved' for me. Embarrassed, I agree to take the seat on condition that I can keep a little boy, relishing an ice cream cone, on my lap. I have climbed over people and seats to get to the privileged seat, the corner one at the left, right at the front, in the very first bus in a convoy of 10.

We are on a 15-mile journey, a short one for me, but the beginning of a very long one for the others. Heading out of Vavuniya town, we pass beautiful birds and pastoral scenery. A peacock crosses our path, but those on the bus don't seem to notice. There's no conversation for they are weighed down by worries, each deep in his or her own thoughts.

As we move out of the town, we encounter fewer and fewer people, but

more and more army camps. Rolls and rolls of barbed wire, concertina as

they are called, glint in the sun. There are large army camps and also

small detachments along the way. Fresh-faced young soldiers, most probably

in  their

teens, man sandbagged and camouflaged bunkers. There is a quiet efficiency

about them, as if they know they have a job to do. The ones close to the

road look up as the convoy passes, some smile.

their

teens, man sandbagged and camouflaged bunkers. There is a quiet efficiency

about them, as if they know they have a job to do. The ones close to the

road look up as the convoy passes, some smile.

We are heading towards the "Crossing" at the Forward Defence Line (FDL) this Tuesday morning.

From five in the morning more than 800 people had gathered outside the gates of the Vavuniya kachcheri, with their bags and baggages. Kerosene oil, coconut oil, cycle tubes and tyres, bottles of coloured aerated water, a child's wooden rocking horse, a tricycle, brightly coloured plastic chairs are strewn along the road. A majority of the people have emerged from numerous 'lodges' that have mushroomed, from the few 'hotels' the town boasts of or from the homes of relatives and friends. In the lodges they have slept on mats in large halls, sharing a common toilet. The more affluent have stayed in the few 'hotels' with the barest of facilities.

Some have spent as much as a week awaiting the 'OK' to start this journey. The journey from the 'cleared' area of Vavuniya to the 'uncleared' areas of the Wanni including Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi. The crossing is through Piramanalankulam. This route had been opened in December 1999, after the "confrontational situation" north of Mankulam, which curbed the movement to the uncleared areas along the Kandy-Jaffna Road.

Getting clearance seems simple on paper. Anyone who wants to visit the uncleared areas fills a form and hands it over with a photocopy of the identity card to the kachcheri and is issued a 'temporary card'. The forms thus collected by the kachcheri are then sent to the army for clearance. Once clearance is given by the army, a list is put up in the kachcheri, people check it out and get a small card with a number. This is their 'passport' to the other side. Passenger traffic between the cleared and uncleared areas takes place on Tuesday and Friday, while food and medicine lorries are sent out on Monday, Wednesday and Thursday and if necessary on Saturday.

When the people gather at the kachcheri gates in the morning like last Tuesday, not-so-polite policemen permit entry only on production of the 'passport'. Then they are herded into sheds in the kachcheri premises and made to queue up _ the first line being for government servants and the sick and the rest for the others. Each one is allowed to carry 40 kilos, with restrictions on certain items.

People complain about the clearance and also 'pass system' that is in force in Vavuniya itself, where anyone including the residents, entering or leaving Vavuniya must carry a pass. Now there are around 15 different types of passes, for various categories of people.But for the army it is also a question of security and protecting innocent people from infiltrators and suicide bombers.

A woman Registered Medical Officer (RMO) at the head of the government

servants' queue laments that the procedure is arduous. Her family _ husband

and two children, one of whom is a mentally retarded son _ is in Colombo

as her husband works at the Fisheries Corporation. "My transfer was approved

a year ago, but the people in Akrankulam in the Kilinochchi area have not

released me  because

there is a lack of staff."

because

there is a lack of staff."

Life has been like this for the past eight years. Her husband who has accompanied her to Vavuniya to see her off, gets back to Colombo and lives in worry until she reaches her workplace in Tiger-controlled territory and sends him a letter that she's okay. She will reach Akrankulam only at 3 a.m. the next day and the mail is irregular so he does not know when he will hear from her again.

When they reached Vavuniya this time, they had got an urgent call that her mother had died in Colombo. By the time they underwent the pass agony and went back to Colombo, her brother had come to Sri Lanka from England for the funeral. "It was easier to come to Colombo from abroad, than from Vavuniya," says the RMO's husband bitterly.

As the queues in the kachcheri lengthen, the noise levels increase. Squabbles ensue between people as to who came first to the queue. Hawkers selling apples, murukku and other what- nots make an easy buck.

For Kumaradasan, 36, this is a 'routine' trip for he is a sick man and needs treatment at the Vavuniya Hospital every month. A father of three, this time he is not only accompanied by his mother, but also by his five-year-old daughter. He is suffering from Parkinson's disease and stays in a lodge while getting treatment. He spends about Rs. 10,000 each time, what with having to pay for accommodation and food here and also the long and arduous journey in the uncleared area.

There are also small business people, who come across to take the things which are in short supply in the uncleared areas.

Around 7.30 a.m. the buses roll into the kachcheri premises and there is a sense of expectancy. Loading begins at about 8. Now the army comes on the scene, with a soldier taking his place at the head of each queue, along with a kachcheri official, both armed with lists of names. A weighing scale hangs on a bar close by. Each person's name is checked against the list, his or her belongings weighed to ensure that only 40 kilos are being taken. The large bags tied on to the bus roof. Rs. 30 is collected as fare for an adult, Rs. 15 for a child and Rs. 30 for each piece of baggage.

Finally by about 9.30 the convoy begins the first stage of its journey to Pirimanalankulam, with a soldier on each vehicle to prevent being stopped at the checkpoints. The mother of the child who is sitting on my lap has come to see relatives in Vavuniya, leaving behind her farmer husband. She has spent a month and is going back home with her two small children. The children seem able to take the journey in their stride though they are only three and five years old.

"We will reach our home in Kilinochchi only on Thursday," she tells me, with one or two government servants on the bus acting as interpreters, while I try to overcome my frustration at the inability to communicate with my own countrymen.

At the turn off to the crossing at Piramanalankulam there comes another delay.

For, by now people who have followed the same procedure in the uncleared areas, are slowly wending their way along a long straight gravel road, towards the army checkpoint at the crossing. Coming from Tiger land, they have got clearance not from the army but from the LTTE. The old, the feeble, the young, assisted by the ICRC make their way to the army checkpoint. Their bags are not as heavy as those heading for the uncleared areas. They bring only a few clothes, treacle, dried fish, arecanut and in a few cases squawking home-bred chickens in cardboard boxes. They cross no-man's land to the FDL, undergo body checks and show documents from the Grama Sevaka .

Then they too are directed to sheds to await thorough bag checks for prohibited items. Army intelligence also questions some of them in small cubicles. There are big water tanks where they could have a drink and cadjan-thatched canteens run by soldiers. There are makeshift toilets too.

The inbound people will wait for the buses which have brought the outbound to unload, and take them to Vavuniya town.

At Piramanalankulam, along the crossing in the middle of no man's land cadjan huts cluster. A white flag with a red cross flies in the dry wind of the Wanni. A few ICRC vehicles are parked along the route. In the distance, at the other end, we can see the Tigers, like tiny midgets, moving around with the ICRC.

We want to take pictures of the people coming along this dusty road. We talk to the ICRC person and he says he would check with the other side as a matter of courtesy. He does so with his phone set and says it's okay. "It's just a matter of courtesy to keep them informed," he repeats.

"No weapons are allowed beyond this point," explains Lt. Milton Tissera pointing to the barricade. "We accept 700 people from there and send out 700 from here. This is also where we accept prisoners and the bodies of dead soldiers."

At five o'clock sharp in the evening the gate made of sticks and barbed wire is closed. However, as dusk falls families seeking refuge on the cleared side and also LTTE surrendees approach the checkpoint. "My soldiers have greeted those who have come to surrender. They come generally under cover of darkness. They throw their cyanide capsule down and we ask them to take off their outer clothing to see whether they are armed. Then we give them to eat if they've not had anything. It's the same with the families who creep along the jungle and seek refuge on this side, with a white flag. About two families come a week," says Lt. Tissera.

Last Tuesday, R. Mugam from Malavi was on his way to Vavuniya Hospital because he had brought his son 10 days before, after being bitten by a dog. He has paid Rs. 200 to the LTTE for a five-day pass.

Others crossover to take international phone calls _ as communication links have broken down in the Wanni - asking relatives to send money. They stay in lodges till the money is sent and cross back again. Some of them have to pay part of it to the LTTE, a few conceded.

Fr. Arulraja had crossed over to attend his brother's wedding at the Mulankavil church. "The people on that side are suffering because of the embargo. Prices of essentials are very high. There's no work and no money. Basic things are not available. People are longing for peace. Therefore, those of goodwill must get-together and promote peace. We must implant this in the minds of all," he stresses.

As I watch, a woman attempts to feed her tiny infant with water from a vanilla essence bottle, to which a teat has been fixed. The baby is obviously not satisfied, for she screams in protest.

"See the suffering we go through," says 74-year-old S. Mylvaganam who has two-days' of stubble on his chin. He has gone to see his daughter who is teaching in Mullaitivu. "The situation is very bad. Prices are high. There are no medical facilities. Milkfood is not available."

He has lived in Colombo for 30 years. Job problems created this call for Eelam, he explains. It came only in 1980. "I don't like this division. Those days we went to Sinhala homes in the south and Sinhalese came to our homes in Jaffna to visit places like Nagadipa. But now we are afraid to speak to each other. Politicians are at fault. There's no direct transport in the Wanni. We have to break journey at three points and pay around Rs. 1,200 for transport alone. Those days the train from Colombo to Kodikamam was Rs. 8.50. The 11.30 a.m. train took us there by 8.30 p.m. Now it is easier to go to a foreign country."

We too leave Piramanalankulam with a heavy heart at the suffering of a section of Sri Lanka's people,wondering whether this is indeed one country and one people.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to