| Plus |

|

|||

| Breathing

poison But recent studies have shown that Colombo’s atmosphere is highly polluted with the level of pollutants such as Sulphur Dioxide (SO2), Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), and Particulate Matter up to 10 micrometers in size (PM10) being higher than the recommended levels. If the current trend continues, officials at the Air Resource Management Centre (AirMAC) warn there will be dire consequences to the general public with an increase in respiratory diseases and decreasing life expectancy. Although Ambient Air Quality Standards have been in place since 1994 and several programmes to improve air quality in the city have been documented over the past decade and a half, hardly any have been implemented. So why is it that we appear to be watching a serious threat grow to crisis proportions? Activities and regulations for the improvement of air quality have been put forward-and either postponed or rejected for reasons such as lack of funds, resources and sometimes political influence, say AirMAC officials. Although AirMAC makes policy decisions, it takes the cooperation of other organizations and individuals to accomplish them.

A Vehicle Emission Testing Programme that was to be put into operation in June 2003 is still held up with tentative plans for beginning it in July this year. Under this programme the Annual Revenue Licence will only be issued for vehicles that conform to certain exhaust emission standards. If vehicles fail to meet the standards they will only be able to obtain the licence after the necessary modifications. Two organizations have agreed to set up Emission Testing Centres all over the island but the operation remains entangled in legal red tape. In 2003 a proposal was put forward to ban the use of 2-stroke engines that are used in three-wheelers. These 2-stroke engines emit hydrocarbons and PM10 in addition to SO2, all of which have grave health effects. Alternatives suggested were to bring back the taxi cabs of older times, give tax incentives to make it easier for three-wheel drivers to buy small cars and to improve public transport facilities. However that would indicate large losses to major companies dealing in three-wheelers and the Cabinet Papers were rejected at the last minute. There is also a lack of proper data on air pollution in the country. Currently there is only one functional Air Quality Monitoring Unit in Sri Lanka located in Fort. In a city such as Colombo, where industries are within the city itself and a large number of vehicles commuting there is a serious need for monitoring units in several parts of the city. AirMAC officials say the cost of a monitoring unit is approximately Rs. 30 million and there are no funds available right now for the establishment of such units. Furthermore there is no way of studying the air quality in other parts of the island, such as Kandy, where the situation could be just as grim. Emissions by thermal power stations, which continue to use cheaper, low-quality fuel, have not even been taken into account. The story of air quality management in Sri Lanka goes back to 1998 when lawyer and Executive Director of the Environmental Foundation Ltd., Lalanath De Silva filed a fundamental rights petition in the Supreme Court stating that the Minister of Environmental Affairs had not taken steps to control the air pollution in Colombo and that he and his family were deprived of the basic right to breathe clean air. In his petition he suggested that there must be standards set for emissions from vehicles, improvement of fuel quality and regulations for the standards of imported vehicles. The Supreme Court ordered that the Minister bring in these regulations to effect by June 2000. Although the regulations were gazetted shortly after the set date their implementation in its entirety is yet to be seen. After the awareness created by this case, in 2001 the Urban Air Quality Management Project was implemented under the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources of Sri Lanka through the assistance of the World Bank. Under this project The Air Resource Management Centre (AirMAC) was established in July 2001. Since many organizations are directly or indirectly responsible for air pollution, several stakeholders were brought in such as the Finance Ministry, Central Environmental Authority, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC), and the Department of Motor Traffic. Every new policy was based on decisions that were discussed and agreed upon by all the stakeholders. One

of the major achievements of this organisation was the introduction

of unleaded petrol in July 2003, seven years before the target.

The health effects of lead poisoning are so severe that it could

affect not only the present generation, but also generations to

follow. While the change involved large-scale technological refurbishment

by the CPC, there is still space for improvement, say officials

at AirMAC. The content of sulphur in diesel has also been reduced

from 10,000 ppm (parts per million) to 3,000 ppm by CPC, which targets

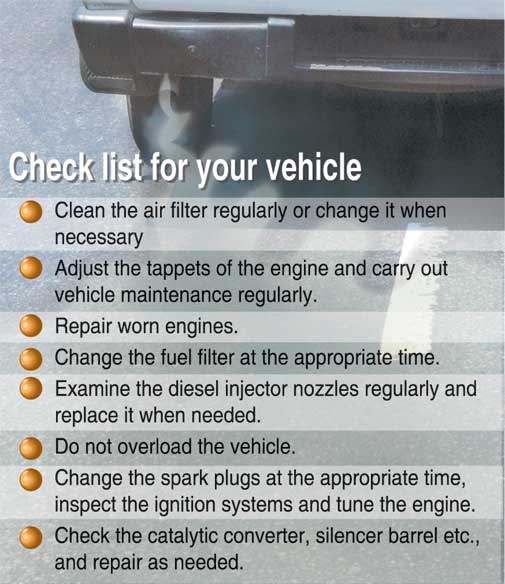

to make it 500 ppm by 2008, which will reduce the emission of SO2. About 63% of the air pollution in Colombo is caused by vehicles and the rest by thermal power stations, factories and the like. Therefore the priority would be to control the pollution caused by vehicle emissions, say officials at AirMAC. This would involve improving fuel quality as well as educating the public on how to maintain their vehicles to increase fuel efficiency. While the proposed

The

lack of air quality monitoring units is obviously a serious lack

in accurately assessing the problem. Why is there only one functional

monitoring unit in Colombo, and how do you hope to remedy the situation? You

say there is a shortage of funds. Why? The

proposed VET (Vehicle Emission Testing Programme) will solve a large

percentage of the air pollution caused by vehicle emissions. Why

has this been continuously delayed? Cabinet

Papers for the banning of 2-stroke engines used in three-wheelers

were rejected. Have you come up with any other solutions to this

problem?

Q: What will happen if air pollution in Colombo goes unchecked? We hope to appeal to donors to fund the placing of more monitoring units as well as mobile emission testing units. We also hope to institutionalise AirMAC, which currently consists of a number of stake holders, into a single separate entity under the Ministry. The set-up may be changed but we must have a stronger mechanism to tackle this problem as it is getting worse. Indoor air pollution is also a serious problem which should be taken into account. Cooking with firewood, usage of mosquito coils, all contribute to indoor air pollution, where mothers and children are the most affected.

|

||||

Copyright © 2001 Wijeya Newspapers

Ltd. All rights reserved. |