| Anagarika

Dharmapala and Sinhala Buddhist ideology

Today, September 17 is the 142nd birth

anniversary of the late Anagarika Dharmapala. The following

are extracts of a speech made by Home Affairs Minister

Sarath Amunugama to a UNESCO conference in Paris and

recently edited for publication in the 2550 Buddha Jayanti

felicitation volume launched by the London Buddhist

Vihara yesterday.

|

| Dharmapala's rationale for the

defence of the Sinhala nation lay precisely in its

historical custodianship of the Buddha's teachings.

His anti-imperialism did not spring basically from

a political or economic critique of imperialism.

To him imperialism had to be resisted since it threatened

the survival and integrity of the traditional Sinhala

way of life which had preserved the Buddha's teaching.

|

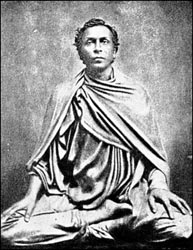

Anagarika Dharmapala, founder of the

London Buddhist Vihara, which celebrates its 80th anniversary

this year, was the outstanding ideologue of the Sinhala

Buddhist revival in Sri Lanka. He provided the conceptual

framework within which the Sinhala Buddhist movement

found expression. Later revivalists like Harischandra

Walisinghe, Piyadasa Sirisena and John de Silva adopted

and worked within Dharmapala's ideological framework.

Dharmapala was a prolific writer and

speaker and has left behind a clear record of his observations

on the plight of the Sinhala Buddhists of his time and

his vision of their historic role. In a life of fifty

years of agitation and exhortation he fashioned a philosophy

which, while drawing from traditional heritage, was

contemporary in that it enabled the Sinhalese to confront

existing realities.

In sum, Dharmapala attempted to redefine

the new identity of the Sinhala Buddhists within a pluralistic,

colonial society. From the middle of the nineteenth

century, the Sinhala Buddhists had made tentative efforts

(religious disputations, a "save the Bo tree"

campaign, anti-Christian pamphleteering) at halting

the missionary advance. It was Dharmapala who finally

channelled these ad hoc responses into a powerful and

effective oppositional platform, which was open to all

Sinhala Buddhists, irrespective of their primary caste,

class and regional affiliations. Indeed, this platform

was open to everybody who identified himself with the

interests of Sinhala Buddhists. Many of the earlier

workers and benefactors of Dharmapala's missions were

Westerners and Indians who sympathised with his philosophy.

A critique of colonial rule

Dharmapala began with an analysis

of the realities of colonial rule: the Sinhala Buddhists

were politically impotent. The Kandyan treaty of 1815,

whereby the chieftains ceded their kingdom to the British

on written guarantees, was a dead letter. In the economic

sphere, Buddhist lands were expropriated, capital was

mainly in the hands of non-Buddhists, and demographic

changes induced by capitalism were to their disadvantage.

The majority of the Sinhala Buddhists were reduced to

the position of consumers of foreign trade goods. Culturally,

their traditional institutions were threatened by the

spread of missionary activity.

Central to Dharmapala's critique of

colonialism was his refutation of the imperialist-missionary

ideology. The sine qua non of colonial ideology in Ceylon

was the rejection of the claims of the Sinhalese regarding

the merits of their religion and culture. As the missionaries

informed Dharmapala in his schooldays, Buddhists were

worshippers of clay idols and false gods, while the

ancient culture of the Sinhalese was symbolised by old-world

customs and the ruins of temples.

Dharmapala launched a frontal attack

on the concept of English superiority. He reversed the

existing relationship and contrasted the past of English

civilisation with that of the Sinhalese.

In place of the imperialist stereotype

of the coloured man as a savage and heathen, Dharmapala,

with a sense of mass psychology, substituted his own

stereotype of the Englishman as a barbarian.

In contrast, the Sinhalese were portrayed

as the heirs to a magnificent civilisation:

“What other nation on earth

is there which could boast of a history of the island,

a history of the great line of kings, a history of religion,

a history of sacred architectural shrines, a history

of the sacred tree, a history of the sacred relics?

“Under the influence of the

Tathagatha's religion of righteousness, the people flourished.

Kings spent all their wealth in building temples, public

baths, dagobas, libraries, monasteries, rest houses,

hospitals for man and beast, schools, tanks, seven-storied

mansions, waterworks and beautified the city of Anuradhapura,

whose fame reached Egypt, Greece, Rome, China, India

and other countries.” (Righteousness, p. 481)

This grandiose view of ancient Sri

Lanka as the centre of a great Buddhist civilisation

was made into an article of faith by the Buddhists --

as compensation for their impotence in colonial times.

It reinforced the view that Sinhalese polity must essentially

be Buddhist.

Dharmapala's rationale for the defence

of the Sinhala nation lay precisely in its historical

custodianship of the Buddha's teachings. His anti-imperialism

did not spring basically from a political or economic

critique of imperialism. To him imperialism had to be

resisted since it threatened the survival and integrity

of the traditional Sinhala way of life which had preserved

the Buddha's teaching.

In doing so, Dharmapala gave contemporary

meaning to two fundamental concerns which are evident

in the history of the Sinhalese. The first is the fear

that the Sinhalese are a "beleaguered nation";

a numerically small community surrounded by hostile

alien races. The classic utterance of the youthful Dutugemunu

-- the epic hero of the Sinhalese -- that he sleeps

huddled up because he is constricted by the sea on one

side and the Tamils on the other, which is part of a

predominant Sinhalese myth, encapsulates this historic

concern. The chronicles of the Sinhalese reinforce this

view of isolation and vulnerability: the Aryan Sinhalese

are threatened by the Dravidian Tamils. The other concern

related to the first, is the need for the Sinhalese

to overcome -- be it by the use of force -- these hostile

and restrictive forces since theirs is a historic mission,

the safeguarding of Buddhism.

These two concerns, which always predominated

in the Sinhalese "psyche", were spelt out

and brought into the open by Dharmapala:

“Two things are before us, whether

to be slaves and allow ourselves to be effaced out of

national existence, or make a constitutional struggle

for the preservation of our nation from moral decay.

We have a duty to perform to our religion, to our children

and our children's children, and not allow this holy

land of ours to be exploited by the liquor monopolist

and the whisky dealer.” (Righteousness, p. 509)

Step towards a Buddhist identity

But what were the distinctive steps

taken by the Sinhala Buddhists of this time to reinforce

their identity? Here we find that scholars like Obeyesekere

and Gombrich have tended to emphasise innovations on

the part of the laity (Obeyesekere, 1979, Gombrich,

1982). However the fundamental problem regarding Buddhist

polity does not rest with changes in lay organisation.

Rather, it pertains more to the total Buddhist organisation

which encompasses developments in the Sangha, their

interrelationships with the laity, and the creation

of a complex relationship in which the Sangha and its

protectors -- be it kings or, as it now stands, lay

leaders -- interact with and reinforce each other.

Viewed in this manner, developments

in Sri Lankan Buddhism under colonial rule assume a

certain coherence and continuity. The highlights of

this development were:-

- the growth of new Buddhist fraternities (nikaya),

particularly on the southern seaboard

- the segmentation of such sects

- the isolation of the chief monasteries of Malwatte

and Asgiriya

- the rise of Buddhist scholarship and disputation

among monks on points of Vinaya

- the growth of Vidyodaya and Vidyalankara Pirivenas

as schools of instruction for monks and centres of

learning and discussion

- the proliferation of Pirivenas in other parts of

the country

- the renewal of Buddhist missionary activity

- the growth of the Buddhist Theosophical Society

- the founding of the Mahabodhi Society.

An early step in the revival movement

was to bring monks into the city and endow them with

temples, which were in many cases mansions of the new

elite donated, as by the kings of the past, to the Sangha.

This led to the creation in the cities of a crucial

institution of the Buddhist revival, the Dayaka Sabha.

These were committees of lay-supporters of temples who

assumed responsibility for the maintenance of the temple,

provided food and clothing for the monks and sponsored

activities such as teaching of the Dhamma to schoolchildren,

discussions on religious and cultural issues, and collection

of money for religious activities. These Dayaka Sabhas

were the main instrument of Sangha-laity co-operation

and were eventually to become the basic tier of Sinhala

Buddhist organisation. Activists of the Buddhist revival

were all members of such Dayaka Sabhas spread throughout

the country.

Transformation of the monk's

role

With respect to the clergy, Dharmapala

consistently emphasised its societal function. He spoke

admiringly of the self-sacrifice and dedication of Christian

missionaries who forsake their kith and kin and live

under trying conditions in Africa and Australia. But

"it is a tragedy that our monks think only of their

convenience and do not try to spread the Sasana of the

Buddha in surrounding lands" (Sarasavi Sandaresa,

6 March 1894). He therefore undertook to recruit a number

of Sinhalese monks for missionary work in India and

England, and undertook personally to pay for their travel,

board and lodging (Sarasavi Sandaresa, 6 March 1894).

But this clerical involvement in the

"good of the world" was at the expense of

meditation and striving for salvation. The scale of

sanctity in Buddhism is measured in terms of distance

from mundane, societal activity.

In this paradigm, a Buddhist must

progress from the 5 precepts observed by the layman

to the 227 precepts (sanvara silaya) which are prescribed

for the Upasampada Sangha. In real life Buddhists would,

to greater or lesser extent, traverse a section of the

continuum.

In modern times the observation of

sila became a highly visible aspect of a monk's vocation.

With the commitment of the monk to live in urban society

this became a primary index to a Buddhist's prestige

rather than meditation, which is the basic aspect of

ascetic salvation-striving. Progressively, the Buddhist

monk's role in society as a disciplined, benevolent

activist was emphasised at the expense of salvation-striving.

The changing role of the layman

If the role of the monk was being

transformed, so was the role of the Buddhist layman.

According to pristine Buddhism, the layman plays only

a peripheral role in the striving for nirvana. He is

too weak to pursue the path of salvation as he is not

willing to shed his societal attachments. For him, the

Buddha propounded a social ethic which Weber characterised

as "an insufficiency ethic of the weak" (Weber,

1962, p. 215).

In terms of popular religion, the

layman looked on the observation of the lay ethic as

a means of merit-making (pin) which enhanced his favourable

kamma, preparing the way for a more rigorous salvation

—striving in a future birth. Another object of

such merit-making was to ensure rebirth at the time

of Maitreya Buddha's appearance on earth so that his

personal intervention could be obtained in salvation-seeking.

Dharmapala's objective at this point

was to build a tightly knit, well-disciplined Buddhist

congregation with a common corpus of belief and awareness

of its strength as a politico-religious group. In this,

he was continuing the work begun by the Theosophists.

For this purpose several changes in traditional Buddhist

lay practice and belief had to be effected. First, an

effort was made to separate canonical teachings from

popular religious practices. Many of these rituals which

did not have a direct scriptural rationale were dismissed

as "excrescences", survivals of Hindu practices

which were antithetical, or at least irrelevant, to

Buddhism. The best statement of such fundamentalist

Buddhism was incorporated in the Buddhist catechism

which was the joint product of Olcott, Sumanagala and

Dharmapala, who may be considered the ideologues of

this viewpoint (Olcott, 1967, vol. 4, pp. 468-9).

Secondly, there was an attempt to

establish a fundamentalist, scriptural Buddhism which

would have been inconceivable in the times of Sinhalese

kings. The full resources of Dharmapala's propaganda

skills — in newspapers, pamphlets, lectures —

were used to this end. Indeed, the use of mass media

technology was a crucial factor in the spread of this

fundamentalist view of Buddhism. Access to Buddhist

texts, particularly the Vinaya Pitaka (rules of discipline)

previously restricted to a handful of monks, was now

made available to many at little cost. These texts and

commentaries on doctrine and practice were discussed,

edited and published, providing a public measuring-stick

whereby both lay and clerical behaviour could be evaluated.

Finally, if the Sinhala Buddhists

were to be organised into a viable socio-political entity,

it became necessary to enunciate for them a code of

lay ethics. While the Vinaya Pitaka laid down a code

of behaviour and discipline in great detail for the

clergy, there was no parallel code for laymen, except

for some injunctions of the Buddha such as the Sigalovada

Sutta.

This lack of concern with lay ethics

is perfectly congruent with the salvation-goals and

methods of the Buddha. But in the political context

of Dharmapala's time, such a unifying code was of paramount

importance. Dharmapala, therefore, compiled and published

a lay code which he entitled a Daily code for the laity,

wherein he set out 200 rules for the lay Buddhist under

the following headings:

1. The manner of eating food. (25

rules)

2. Chewing betel. (6 rules)

3. Wearing clean clothes. (5 rules)

4. How to use the lavatory. (4 rules)

5. How to behave while walking on the road. (10 rules)

6. How to behave in public gatherings. (19 rules)

7. How females should conduct themselves. (30 rules)

8. How children should conduct themselves. (18 rules)

9. How the laity should conduct themselves before the

Sangha. (5 rules)

10. How to behave in buses and trains. (8 rules)

11. What village protection societies should do. (8

rules)

12. On going to see sick persons. (2 rules)

13. Funerals. (3 rules)

14. The carters' code. (6 rules)

15. Sinhalese clothes. (6 rules)

16. Sinhalese names. (2 rules)

17. What teachers should do. (2 rules)

18. How servants should behave. ( 9 rules)

19. How festivals should be conducted. (5 rules)

20. How lay devotees should conduct themselves at temple.

21. How children should treat their parents. (14 rules)

22. Domestic ceremonies. (1 rule)

In this lay charter was combined Dharmapala's

fundamentalist interpretation of Buddhism and his view

of corporate traditional Sinhala culture. What is significant

is the attempt to reconcile Buddhists to living a "successful"

life in society, liked by parents, relatives, friends

and priests, capitalistic but generous and considerate.

It was in essence a bourgeois world view, which takes

for granted the prevailing social hierarchy. For example,

one section of Dharmapala's lay code is devoted to the

obligations of servants and carters. Servants are exhorted

to work hard and promptly, be enthusiastic about the

worldly success of their employer and avoid any hostility

to the employer by word or thought, much less deed.

This charter performed two vital functions.

First, it could unite the Sinhala Buddhists under the

leadership of the native elite. It was a common platform

cutting across caste and kin lines and eliminating village

cultural practices which had a specific regional or

caste focus. Secondly, it incorporated all those puritanical

characteristics which were proclaimed as desirable by

the missionaries. Thus the national bourgeoisie, upwardly

mobile and anxious to drop its village affiliations,

could easily approve of it and adopt it as their ideal

life-style.

The modern Anagarika

The same functional requirements that

were bringing subtle change in the monks' vocation were

also creating new forms of religious commitment. The

absence of a lay Buddhist authority, classically represented

by the king, which had forced a change in the monks'

role in contemporary Sinhala society, also led to the

creation by Dharmapala of the role of the modern Anagarika.

The Anagarika (homeless) role which

was central to Dharmapala's religious charisma was probably

born, as I shall describe later, out of his own psychological

needs. But he was able to adapt them to the functional

needs of modern Buddhism. According to Buddhism,a monk

is an Anagarika, homeless, celibate and dedicated to

his personal salvation, as evidenced by his repudiation

of all ties that bind him to society (Weber, 1962, p.

214). An important element of Buddhist religious authority

is derived from renunciation, which finds its clearest

expression in the life of the Buddha, a model for all

Buddhists.

Dharmapala too was a renouncer coming

from the richest of Colombo Sinhala families. He renounced

all those symbols of affluence that his contemporaries

sought and dedicated himself to the revival of Buddhism.

Obeyesekere attributes this to an "identity crisis"

caused by cultural marginality (Obeyesekere, 1979, p.

296).

Conclusion

In the final perspective, what can

be said of the role played by Dharmapala? During the

times of Sinhala royalty, the Buddhist church and its

priests had been protected by the king. The extinction

of Sinhala royalty deprived the church of a benefactor,

and the church had lost all power to enforce its control

over society. This was recognised by the Christian missionaries,

who actively challenged the unprotected Buddhist church

and made impressive gains in converts. Once the national

religion, Buddhism became merely one of a number of

competing churches.

Furthermore, the major institutions

of Buddhism were linked with the feudal social structure

at a time when the spread of capitalism was redefining

social relationships. A readjustment, a charting of

new directions was urgently needed if a Buddhist social

fabric was to be maintained. It was Dharmapala who imposed

his vision of the inseparability of Buddhism and Sinhala

society, and promoted the emergence of a modern version

of the historical relationship between religion and

lay society that had existed in Sri Lanka since the

third century BC when Buddhism was first introduced

to the country.

|