By Asanka Wijesinghe and Eleesha Munasinghe

Sri Lanka’s preferential access to the vital European Union (EU) market faces fresh challenges after the European Parliament’s special resolution adopted in June 2021. The resolution calls for an assessment on “whether there is sufficient reason, as a last resort, to initiate a procedure for the temporary withdrawal of Sri Lanka’s GSP+ status.” The GSP+ is a non-reciprocal trading arrangement whereby Sri Lanka does not have to lower tariffs in return but is required to implement certain non-trade related conventions to benefit from preferential access. The GSP+ arrangement slashes import duties to zero for vulnerable low and lower-middle-income countries that implement 27 international conventions related to human rights, labour rights, environment protection, and good governance. This article assesses the impact of a hypothetical withdrawal of GSP+ on Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU: the largest single trading bloc, with the United Kingdom (UK), accounting for 30% of Sri Lanka’s exports.

Impact

A possible withdrawal of GSP+ will increase the tariffs for Sri Lankan products up to the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs. Consequently, products coming from Sri Lanka will be more expensive in the EU market, directly reducing the export demand from Sri Lanka. However, Sri Lanka’s competitors that continue to benefit from the EU’s GSP will face zero preferential tariffs. Thus, in addition to the trade destruction effect, with the relative price of goods from Sri Lanka being higher, the trade will be diverted to those competitors. Using a partial equilibrium analysis, one can ex-ante quantify these effects of GSP+ withdrawal. Assuming the UK will follow the EU lead, and Sri Lanka will face the lower bound of relevant MFN tariffs, partial equilibrium estimates show that Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU will fall by US$627 million (Table 1). The simulations are done taking 2019 as the base year.

Table 1. Impact of the withdrawal of GSP+ on Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU

|

HS chapter |

Product description |

Current tariff |

The lower bound of MFN tariff |

Exports in 2019 (USD million) |

Exports after a withdrawal of GSP+ (USD million) |

Trade loss (USD million) |

|

61 |

Knitted and crocheted apparel |

0.0% |

8.9% |

1,489.5 |

1,172.8 |

316.7 |

|

62 |

Woven apparel |

0.0% |

8.9% |

897.6 |

719.9 |

177.7 |

|

24 |

Tobacco and manufactured tobacco substitutes |

0.0% |

22.8% |

68.1 |

13.9 |

54.2 |

|

03 |

Seafood |

0.0% |

7.5% |

115.0 |

94.9 |

20.1 |

|

40 |

Rubber and articles |

0.0% |

4.5% |

284.9 |

271.1 |

13.8 |

|

21,15,09,20,85,07,87,95,63,06,69,64,57,71,16,44 |

Other |

0%-3.3% |

2%-33.4% |

595.7 |

550.7 |

45.0 |

|

Total |

3,450.8 |

2,823.3 |

627.5 |

Sources: Based on the authors’ estimates of partial equilibrium analysis using SMART.

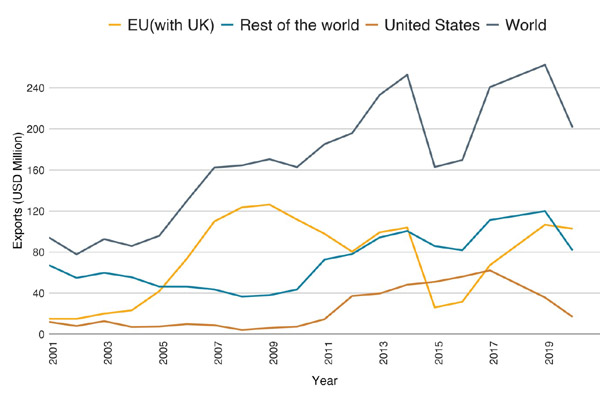

As Table 1 shows, the worst-hit sectors are apparel (HS 61 and HS 62), tobacco (HS 24), seafood (HS 03), and rubber (HS 40) sectors. The combined loss for the apparel sector will be as much as $494 million, and it is 79% of the total estimated trade loss. In addition, the seafood sector is deemed to lose $20 million or 17% of the sector’s 2019 exports to the EU. Thus, losing preference to a vital market will be hard for the recovering seafood industry (figure 1).

There are two caveats of an ex-ante impact assessment of this kind. The first is that the analysis is based on assumed elasticities. However, the assumptions are not overly restrictive. The second is that all the eligible exports from Sri Lanka do not utilise the GSP+ facility. Thus, the actual impact will be contingent upon the utilisation ratio. However, after Sri Lanka regained GSP+ preference in 2017, the utilisation ratio increased, reaching 61.8% in 2019, improving from 55.1% in 2017. Therefore, the increasing utilisation ratio makes the potential impact still significant.

Notably, there is a variation of the utilisation rate within the HS chapters, as shown in Table 2. The apparel sector will be relatively resilient to a loss of preference as its utilisation ratio was 52% in 2019. However, a loss of preference will halt any industry drive that aims to increase the utilisation rate and then expand the market share in the EU. Further, the 2010 loss of GSP+ inflicted high costs to the industry. As seafood, rubber products, and footwear sectors utilise more than 90% of GSP+ preference, those sectors will be more vulnerable to the shock. Indeed, the difference between GSP+ preferential tariff and MFN tariff for seafood is higher -zero versus 7.5% respectively (Table 1)- aggravating the impact.

Figure 1: Sri Lanka’s seafood exports from 2001-2020

Notes: The deep plunge around 2015 resulted from the EU sanctions on seafood exports from Sri Lanka on the ground of Sri Lanka’s failure to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The impact of the previous preference loss is visible around 2010 in the graph.

Source: Authors’ illustrations using Trademap data.

Table 2. GSP+ utilisation ratios for major exports by Sri Lanka in 2019

|

GSP Section |

HS chapter |

Product description |

GSP+ Utilisation Ratio |

|

|

2017 |

2019 |

|||

|

S-11b |

61/62/63 |

Knitted and crocheted apparel/ woven apparel/other made-up textiles |

42.2% |

52.3% |

|

S-07b |

40 |

Rubber and rubber articles |

96.6% |

96.4% |

|

S-01b |

03 |

Seafood |

95.3% |

99.5% |

|

S-12a |

64 |

Footwear |

63.1% |

90.6% |

|

S-16 |

85 |

Electronic machinery and equipment |

38.3% |

47.6% |

|

All Sections |

|

|

55.1% |

61.8% |

Source: Authors’ illustration using data from Generalised Scheme of Preferences statistics, European Union

Future steps

The losses from GSP+ preference will be significant and heterogeneous across sectors. The GSP+ also opens the door for EU investments as outsourcing production to preference receivers is beneficial to the EU. In addition, sectoral losses may spillover to the overall economy exacerbating poverty and income inequality. Thus, avoiding such losses should be a political priority for policymakers. Less dependence on the EU market is a widely suggested strategy. Diversification is indeed beneficial when it is done for economic reasons. However, ad-hoc moves to diversify to escape from unresolved political issues will not do much good. The EU market is a high-end export destination for Sri Lanka. The quality improvements, product standards, and consumer preferences positively challenge the Sri Lankan exporters to improve product quality and competitiveness.

Additionally, a non-reciprocal preference for various products incentivises product diversification away from traditional exports into more complex products like electronic equipment, including semiconductors (HS chapter 85). Therefore, while Sri Lanka should work to secure the GSP+ resolving the current political issues and focus on fully utilising GSP+ preference in the short run. In the long run, as GSP+ is contingent upon income level, Sri Lanka will lose it someday, and as such should enter into reciprocal trade agreements with the EU and other high-end markets, including the US.

(Asanka Wijesinghe is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) while Eleesha Munasinghe was a research intern at IPS. She is currently an undergraduate (Economics and Finance) at New Castle University in UK).

Leave Comments