Deep Water Bunkering Terminal at Port of Colombo: Feasibility & Economic Impact – Part 1

By Shashi Dhanatunge

A former Chairman of Ceylon Shipping Corporation, Director of Ceylon Petroleum Corporation and Vice Chairman of Civil Aviation Authority. Currently holding Board positions in several local and overseas companies

Introduction

The Port of Colombo, Sri Lanka’s busiest harbour, is strategically located on East-West shipping lanes. However, its current bunkering facilities are modest when compared with it’s world ranking. Establishing a deep water bunkering infrastructure at Colombo would allow Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) and Ultra Large Crude Carriers (ULCCs) to call for replenishing stocks. This report evaluates the required infrastructure upgrades, investment costs, timeline, revenue projections, and economic impact of such a project. It also compares outcomes with and without the project and identifies a suitable development zone at the port.

Infrastructure Upgrades for Bunkering using VLCC/ULCC (Panamax & Aframax)

To accommodate VLCCs/ULCCs and high-throughput fuel operations, Colombo’s port infrastructure must be enhanced:

-

Mooring Facilities: A dedicated oil berth (or single-point mooring) capable of berthing VLCC/ULCC is crucial. This includes heavy-duty mooring dolphins, fenders, and navigation aids to handle vessels over 300 m LOA. The berth should be sited to avoid impeding container traffic – likely at the harbour outer edge or near the new breakwater.

-

Tank Farm & Pipelines: Onshore storage must expand significantly. New tank farms (e.g. 100,000–200,000 m³ total capacity for various fuel grades) with pipeline connections to the berth are needed for high-speed discharge. For example, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port built a tank farm (initial 500,000 tonnes annual capacity) as part of its bunker terminal. Colombo would require a comparable or larger facility. Pipelines should support rapid transfer (loading/unloading rates to turn around a VLCC within ~24 hours).

-

Pump and Loading Systems: High-capacity pumps and manifolds must be installed to enable high-speed fuel discharge. Modern bunkering terminals use multi-product pipelines and loading arms to move fuel efficiently. This ensures a VLCC can discharge cargo quickly into shore tanks, and bunker barges can be loaded in minimal time to serve client vessels.

-

Bunkering Barges: The project should include a fleet of fuel barges capable of bunkering ships at anchorage or alongside. These barges (e.g. 1,000–5,000 DWT) would load from the tank farm and deliver fuel to large container ships, etc. High pumping rates (e.g. 500+ m³/hour) on barges will reduce vessel idle time.

-

Support Infrastructure: Ancillary needs include a dedicated control room, safety systems (firefighting, spill response), and possibly a blending facility for different fuel grades (to supply VLSFO, MGO, etc. per IMO 2020 rules). Upgrades to port utilities (power, security, access roads) around the bunkering zone will also be required.

These upgrades leverage Colombo’s existing deep water harbour but tailor it for oil logistics. Notably, a prior project relocated a 10 km crude oil pipeline and offshore moorings during harbour expansion, indicating the scope of works needed to integrate bunkering into port operations.

Benchmark Costs & Capital Investment Estimate

Capital costs for a bunkering hub can be substantial. We derive estimates from similar international projects and Colombo’s context:

-

Tank Farm and Berth Construction: Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port built a bunker terminal for $76.5 million in 2010, which included fuel tanks (LPG and oil) and a jetty, yielding around 500,000 tonnes initial capacity. Given Colombo’s larger scale (targeting VLCCs), a more extensive facility is needed. A single deep water berth with dredging might cost on the order of $40–60 million (comparable to large oil jetty projects). Storage tanks (e.g. 100,000 m³ across multiple tanks) and pipelines could add another $50 million.

-

Supporting Infrastructure: Pump stations, automation, safety systems, and barge acquisition may require $20–30 million. For instance, buying or retrofitting bunker barges and installing high-capacity loading pumps would be in this range.

Using these benchmarks, we estimate the total initial investment around $120–150 million for a fully operational deep water bunkering facility at Colombo. This assumes one VLCC-capable berth and a moderate tank farm. A larger multi-berth oil terminal (for simultaneous discharge and loading) could raise costs towards $300 million, but the initial phase is likely scaled down. Table 1 summarizes the rough cost breakdown:

|

Cost Component |

Estimated Cost (USD) |

|

Deepwater Berth & Dredging |

$50 million |

|

Tank Farm (storage tanks) |

$40 million |

|

Pipelines & Pump Systems |

$20 million |

|

Bunkering Barges (fleet) & Marine Pollution Preventive Systems |

$15 million |

|

Total Initial Investment |

$125 million |

Table 1: Estimated capital costs for Colombo deep water bunkering facility (Phase 1). Benchmarked to similar port projects.

For context, major oil-terminal projects elsewhere have seen similar scales: the new Kipevu Oil Terminal in Kenya (4 berths including a VLCC berth) cost about $385 million, while Oman’s Duqm port recently added a bunker terminal integrated with a refinery (part of a multi-billion project). Colombo’s investment in the ~$100–150M range is reasonable for a first-phase development focusing on one berth and storage, given the Hambantota experience. Notably, Sri Lanka’s government is already planning to invite private sector to partner and invest into development of two oil berths in the Northern part of the Port of Colombo. Hopefully, the limited draft towards the North of Colombo Port shall not constrain the full development potential and optimisation of the opportunity. Therefore, this proposal suggests the government to consider an alternative area for the development.

As an example, if the Sapugaskanda Oil Refinery Expansion & Modernisation (SOREM) project proposed by the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) becomes a reality then it is imperative that a deep water bunkering terminal is established in Colombo for its best outcomes, competitiveness and sustainability. One of the available options is to look at a Single Point Mooring Buoy (SPMB) installed off shore in the Northern end of the Port of Colombo.

Timeline for Implementation

Developing the bunkering infrastructure would be executed in phases over the short, medium, and long term:

-

Phase 1: Planning & Approvals (Short Term, ~1–2 years). This includes feasibility studies, environmental impact assessments, design work, and financing arrangements. Regulatory approvals (from Sri Lanka Ports Authority, Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, etc.) are obtained in this phase. By the end of Phase 1, contracts for construction and equipment procurement would be in place.

-

Phase 2: Construction & Commissioning (Medium Term, ~3–5 years). Major works commence, such as dredging the berth pocket and access channel (if needed), building the jetty/berth structure, and constructing tank farms and pipeline networks, which could take up to 3 years. By year 4, initial infrastructure could be ready. Commissioning and testing (pumping systems, safety drills) would occur toward the end of this phase. Outcome: initial operations begin by year 5.

-

Phase 3: Expansion & Optimization (Long Term, 5–10 years). In the longer term, the facility can be expanded in stages based on demand. This might involve adding more storage tanks for future fuels such as Biofuels and Methanol, a second berth or improving loading infrastructure for higher throughput. It also includes business ramp-up – marketing Colombo as a refuelling stop to shipping lines. By year 10, the facility would aim to reach steady-state high volumes (potentially handling 4.5–5.0 million tonnes of bunker fuel annually, as discussed next).

Milestones: Short-term (years 1–2) would yield project kick-off and ground-breaking; medium-term (year 5) sees the first bunkering operations underway; long-term (beyond year 5) realizes full capacity and additional services (e.g. lubricant supply, blended fuels). This phased timeline allows initial revenue generation while scaling up gradually.

Revenue Projections (10-Year Outlook)

Once operational, the deep water bunkering terminal can generate multiple revenue streams: fuel sales, port fees, and ancillary services. Below is a 10-year projection assuming a conservative ramp-up (Table 2):

|

Year |

Bunkering Volume (MT) |

Fuel Sales Revenue (US$) |

Net Profit (US$) |

|

1 |

1,500,000 |

$1.0 billion |

$25.0 million |

|

5 |

4,000,000 |

$2.7 billion |

$67.5 million |

|

10 |

5,000,000 |

$3.5 billion |

$87.5 million |

Table 2: Hypothetical revenue/profit trajectory over 10 years. Assumes average bunker fuel price of $650-700/tonne and approx. net profit margin of 2.5%.

These figures illustrate the potential scale. By year 10, handling 5 million tonnes of bunkers could bring in over 3.5 billion dollars in fuel turnover. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota bunker terminal, after leasing to Sinopec, handled around 600,000 tonnes of bunkers in 2023 – a useful real-world benchmark for Colombo’s ambitions. Colombo could target nearly ten times volume within a decade, given its greater ship traffic. The profit margins in bunkering are typically thin – global players like World Fuel Services report margins on the order of only $3–5 per tonne. I have assumed $16/tonne in the later years by factoring in value-added services and higher-margin products (e.g. marine gasoil, biofuel and methanol). Even with modest margins, the large volume yields a solid cash flow.

Return on Investment (ROI): If the initial investment is $125 million, and by year 10 net profits reach $87.5 million/year, the project’s simple payback period would be 4 years. The internal rate of return (IRR) could be on the order of 29-31% over 20 years (assuming volumes continue to grow beyond year 10). More optimistic scenarios (higher regional demand or higher margins) could improve ROI, while risks (under-utilization or oil price volatility) could lower it. One mitigation is leasing the facility to experienced operators (as done with Hambantota’s bunkering leased to Sinopec) to ensure high utilization and steady rent/royalty income for the port regardless of fuel price swings.

In addition to direct fuel sales, Colombo Port Authority would earn ancillary revenues: berth fees from tankers, wharfage on fuel, and services (water, sludge disposal, etc.) for ships calling to bunker. These add to the ROI indirectly. Overall, the 10-year outlook suggests the project can be financially viable, with cash flows ramping up in the mid-term and a respectable ROI in the long run, provided Colombo captures a share of the regional bunker market.

Economic Impact: With vs. Without the Project

Investing in a deep water bunkering terminal would have significant economic implications for Sri Lanka. Below we compare scenarios:

With Deepwater Bunkering Project:

-

Boost to Port Competitiveness: Colombo would offer one-stop service (container transhipment and refuelling), attracting more vessel calls. Ships that might bypass Sri Lanka could choose Colombo to bunker, increasing maritime traffic. This underpins Colombo’s status as a regional hub.

-

Diversification of Port Services: With the development of Indian ports (eg. Vizhinjam) the container transhipment business in Colombo Port would be at stake. Adding West Container Terminal (WCT) and East Container Terminal (ECT) to supply side might result in overcapacity (from current 7.1 million TEUs to 15.1 in 2027) than the residual demand for the transhipment business, with the result that the income for SLPA would be declining. Therefore, as a diversification of port services, SLPA must seriously look for developing Colombo Port as a proper Maritime Hub. The obvious option is developing bunkering business to international level with competitiveness with economies of scale. Deep draft main line container vessels that are expected to call forthcoming transhipment hubs in India need bunkering. Colombo being closer to main sea route has the competitive edge for bunkering business when compared with Indian ports.

-

Revenue and Forex Earnings: Annual bunker sales of hundreds of millions of dollars translate into substantial income. Even at a few dollars margin per tonne, much of the fuel value flows through the local economy (through port fees, supplier contracts, labour wages, and possibly some local refining/blending if developed). It reduces outflow, as currently many Sri Lankan ships refuel abroad.

-

Employment and Skills: The project would create jobs in construction (hundreds during 3-5 year build) and operation (terminal staff, barge crews, maintenance, laboratory technicians for fuel quality, etc.). It also develops local expertise in oil terminal management.

-

Strategic Fuel Reserve: A large tank farm increases Sri Lanka’s storage capacity for petroleum. This can improve energy security – Colombo could hold buffer stocks of marine fuel and even Jet A1 aviation or power fuels if needed, reducing vulnerability to supply shocks.

-

Value-Added Services: Over time, Colombo can expand into blending low-sulphur fuel, supplying biofuels, methanol, LNG bunkers (future option), and other services, moving up the value chain. An ecosystem of marine services (ship chandling, surveys, minor repairs during bunkering stops) could flourish, adding further economic value.

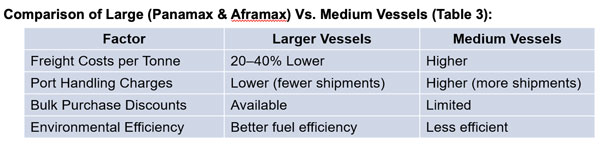

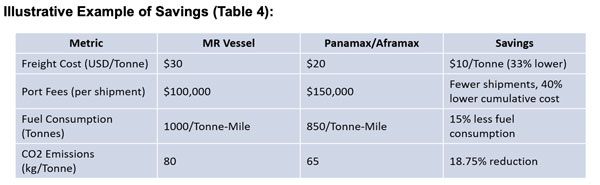

Illustrative Example of Savings (Table 4):

Without the Project:

-

Colombo remains primarily a container/transhipment port without major refuelling activity. Ships must detour to Singapore or Fujairah for bunkers, meaning lost opportunities. Sri Lanka would continue to rely on its smaller bunker setups (e.g. the existing Colombo oil berth from 1997 and the modest tankage, plus Hambantota’s facility) which limit volume.

-

The foregone revenue is significant: for example, 1.0 million tonnes of bunkers sold elsewhere means $650-700 million in turnover not captured in Sri Lanka. The port would miss out on bunker-related fees and might see slower growth in throughput (since some shipping lines prefer ports where they can also refuel).

-

Strategically, Sri Lanka remains less competitive relative to regional ports. With no new investment, Hambantota’s bunkering (now under foreign lease) might siphon whatever regional demand exists, and Colombo would not emerge as a true maritime hub beyond containers. Furthermore, without expanded tank capacity, the country’s ability to secure fuel at lower prices (by importing in bulk via VLCC) is limited.

In summary, the economic outcome with the project is far superior: higher port revenue, improved balance of trade (by servicing foreign ships), and multiplier effects on the economy. Sri Lanka could become a premier bunker supplier in South Asia, an official goal noted by the Ports Authority (Sri Lanka: Ports as a Premier Bunker Oil Supplier). Without it, Colombo risks ceding the bunker market to competitors and remains vulnerable to regional competition. Furthermore, the government’s plan to expand and modernise the Sapugaskanda oil refinery (SOREM project) shall not bring the best outcomes, once again.

Impact on Bunker Fuel Pricing

Current Pricing (Illustrative) - Table 5:

|

Location |

MOPS Base |

Premium |

Final Price |

|

Singapore |

$550 |

$10–15 |

$560–565 |

|

Colombo |

$550 |

$40–70 |

$590–620 |

Future Pricing (Post-Development illustrative) – Table 6:

|

Location |

MOPS Base |

Premium |

Final Price |

|

Singapore |

$550 |

$10–15 |

$560–565 |

|

Colombo |

$550 |

$15–25 |

$565–575 |

Price gap narrows from $50+ to <$10, making Colombo competitive. Allows Sri Lanka to hedge, import in bulk, and reduce buyer costs.

Development Zone Selection & Layout

After evaluating Colombo’s geography, the ideal zone for the bunkering hub is the southwestern side of the port, leveraging the newly reclaimed land of Colombo Port City. This area (269 ha of reclaimed land adjacent to the main harbour) provides ample space for tanks and is directly accessible from the deep water entrance channel. Key advantages of the site include: proximity to deep water (for VLCC berthing along the new breakwater) and isolation from main container terminals (for safety and to avoid traffic conflict).

A bunkering berth could be created seaward of this breakwater or alongside it, where deep drafts are naturally available. The tank farm would lie just behind, on land that is currently underutilized (Port City’s developmental zone). This positioning ensures bunkering operations have direct sea access and ample safety buffer, while remaining within port limits. Additionally, the northern waterfront of Colombo (around Bloemendhal or the existing oil jetties) was considered, but space constraints and shallower depth make it less optimal than the Port City zone.

Conclusion

Developing deep water bunkering at Colombo Port is feasible and economically compelling. The required upgrades – though capital-intensive – draw on proven models from other ports. An investment on the order of $125+ million could be recouped through steady growth in bunker sales, especially given Colombo’s strategic location on global shipping lanes. Over a 10-year horizon, the project can transform Colombo from purely a container hub into a dual hub of containers and fuel, with millions of dollars in new revenue and a stronger competitive position.

Crucially, the comparison of scenarios shows that not pursuing this project carries a high opportunity cost. With regional competitors like Singapore, Fujairah, and even Hambantota capturing bunker markets, Colombo cannot afford to lag if it aspires to be a leading Indian Ocean maritime centre. By investing in a state-of-the-art bunkering facility (potentially via public-private partnership to mitigate state burden), Sri Lanka stands to gain long-term economic dividends and improve energy security. The Port City development provides an ideal platform to integrate this new oil terminal in a way that complements Colombo’s expansion. Otherwise, the available option is to look at a Single Point Mooring Buoy (SPMB) installed off shore in the Northern end of the Port of Colombo due to the limited draft.

In conclusion, establishing deep water bunkering infrastructure at Colombo is a forward-looking move. It is a technically feasible endeavour with manageable investment needs (supported by analogous projects’ data) and offers a favourable ROI when considering not just direct profits but also wider economic multipliers. With phased execution and strategic partnerships, Colombo can realistically become a regional bunkering hub, elevating its port into a more diversified and resilient economic asset for Sri Lanka.

References and Sources

-

Sri Lanka Ports Authority – “Ports as a Premier Bunker Oil Supplier” (SLPA News) (Sri Lanka: Ports as a Premier Bunker Oil Supplier).

-

Wikipedia: Port of Colombo – statistics on depth and capacity.

-

Wikipedia: Hambantota Port – bunkering terminal cost and capacity.

-

Ship & Bunker News – report on planned Colombo Port City bunkering investment (Investor Plans Colombo Bunkering Facility in Sri Lanka - Ship & Bunker).

-

World Kinect Corp. – bunker fuel sales margin data.

-

Port Technology International – Colombo South Harbour expansion details.

-

Wikimedia Commons – Colombo harbour imagery (for layout visualization).

-

Still No Comments Posted.

Leave Comments