Absolute stillness, the stillness of the jungle, accentuated only by the call of birds from the lotus-studded wewa.

Suddenly a humming and whining begin, shattering the stillness. A bulldozer is at work………up and down, leaving a large swathe of land cleared of everything.

|

| Smouldering Dahaiyagala. |

What is left is only a trail of destruction – giant trees such as weera and myla on their sides, the scrub jungle no more and the tall grasses cleared. Some of the trees and shrubs have been set ablaze, with patches of areas still smouldering.

This is the fate, since Monday, of part of the Dahaiyagala sanctuary and animal corridor, covering about 2,685 ha, on the northern border of the Uda Walawe National Park, in clear violation of the large green boards of the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWLC). See pic of board.

For, this is where the elephants including four majestic tuskers (one being ‘Walawe Raja’) the sloth bear, the leopard and the sambhur roam. ‘Walawe Raja’, the tallest of the tuskers in the area graces the posters of the DWLC and has also been portrayed in a BBC documentary titled, ‘The Last Tusker’.

“People have been brazenly clearing the sanctuary in violation of the law,” lamented a wildlife official, pointing out that the culprits want to put up a barrier, blocking the animal corridor on the boundary of the Uda Walawe National Park.

The Dahaiyagala corridor links the National Park with Bogahapattiya described by conservationists as the “last remaining savannah (talawa) and intermediate zone forest to remain intact in the southern part of Sri Lanka”.

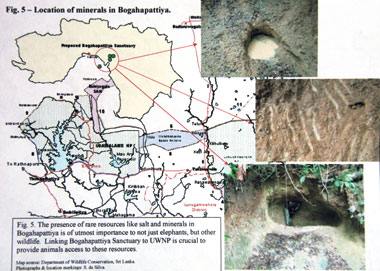

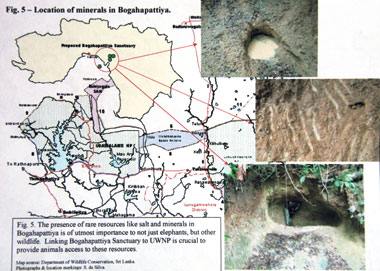

The blocking of the Dahaiyagala opening into the National Park (see map) will prevent the elephants, the sloth bear, the leopard and the sambhur whose home range is Bogahapattiya, from accessing the National Park. Dahaiyagala also has many wewas including Pokunutenne which has water throughout the year, which the animals use. The smaller ones which are seasonal dry up during the drought.

The other tanks which do not run dry are Uda Walawe and Mau-ara which are within the National Park itself.

The stories doing the rounds in Uda Walawe are that a few politicians in the area, along with some officials, have unlawfully taken the lead in efforts to shut the animal access point through Dahaiyagala into the National Park.

“The speculation is that because water comes to the area after the Weli-Oya scheme completion, they want to turn the Dahaiyagala sanctuary into either cultivation lands or grazing grounds for cattle, to win votes from the people,” said another official.

|

| A bulldozer at work |

Uda Walawe had been gazetted as a National Park in 1972. Identifying the importance of Dahaiyagala, it had been declared a sanctuary on June 7, 2002 (No. 1239/28). Taking into consideration the importance of Bogahapattiya, with its high biodiversity including rare species of flora, like the mandoran tree (endemic only to the Uva area), there is a proposal to make it a sanctuary as well.

“No one except DWLC officials can clear any state land within a sanctuary,” stressed Environmentalist Jagath Gunawardena citing Section 7 of the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance.

Amidst serious allegations that no wildlife official had visited the area under threat, the need of the hour, as even the humble people of Uda Walawe urge, is for the highest authorities to get involved now.

Stop the rape of Dahaiyagala right now.

The importance of Bogahapattiya sanctuary and Dahaiyagala animal corridor

Bogahapattiya is special because it is the home range of elephants, the sloth bear, the sleek leopard and the magnificent sambhur.

Bull-elephants including four tuskers only cross to the Uda Walawe National Park using the Dahiyagala sanctuary and corridor during June-July-August, when they are in musth to find mates, The Sunday Times understands.

|

| The circled portion in map indicates the area under threat |

Bogahapattiya is also a lure for elephants, because seven salt minerals essential for them are found in natural abundance here, it is learnt. “These salt ‘licks’ are needed for their gene pool,” a wildlife expert who declined to be identified told The Sunday Times. “They will lose these licks, which in turn will affect their general health and breeding activity.”

The sloth bear, meanwhile, has not been sighted in the Uda Walawe National Park for a long time and wildlife experts believe that it has become extinct there. Their hope is that there will be natural regeneration or enrichment of the national park someday with the sloth bear crossing over from Bogahapattiya.

Meanwhile, Bogahapattiya is not only an important catchment and watershed area but also a water source for the Walawe, Weli Oya and Mau-ara.

Orders to stop!

I have instructed the Additional Director (AD) of the area to take measures to stop the destruction, assured the Director-General of the Department of Wildlife Conservation, W.A.D.A. Wijesooriya, when contacted by The Sunday Times.

The instructions had been issued at a meeting with the AD in Colombo on Thursday.

If Dahaiyagala is closed to animals, what will happen?

- When elephants lose their home range they usually cannot and do not adapt and will gradually die off. “It will turn into another elephant cemetery,” said elephant expert Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando, Chairman of the Centre for Conservation and Research, when contacted by The Sunday Times.

- A human-elephant conflict will be created in the area, as the restriction particularly of male elephants from roaming freely into the Uda Walawe National Park and Bogahapattiya. These islolated elephants will create problems and raid cultivations around the Dahaiyagala area. With the loss of crops, the people will be angered into harming the elephants. “Waga bim wala vedi kanna venne alinta,” lamented a wildlife official explaining that the elephants will fall victim to bullets.

|