22nd July 2001

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business|

Sports| Mirror Magazine

Count me too, sir

A beggar walks up to Punyasiri Manawaduge and asks him, "Sir, can you count me?"

Initially surprised, the young law undergraduate gathers his wits and responds, "Of course. Come, come let me get some details."

I am at Town Hall on July 17, census day with a group of 12 enumerators, dubbed 'the outdoor' team, collecting details of Colombo's street people and homeless.

It is simply amazing. One would have anticipated reluctance, hesitancy,

indifference, apathy and most of all, ignorance. None of this happened.

Nor did a single beggar ask for money from the enumerators or census takers.

The response and demand to be counted or have personal details taken in

Sri Lanka's first population census in 20 years were unanimous from the

most ignored  segment

of society.

segment

of society.

Walking along with Manawaduge, one of thousands of university students recruited by the Census Department as enumerators, we encounter Upul Pathmasiri and his family who live on the pavement next to the Seylan Bank branch near the Dewatagaha mosque.

The Pathmasiri clan, husband, wife and three small children, sleep next to a cart that he uses to sell fruits for his livelihood. "When and where were you born?", " What is your religion?", "Are you married?", "What is your profession?", "Did you go to school" and "What was the last examination you passed or up to what standard did you study?" are some of the questions posed to Pathmasiri by Manawaduge.

The young census taker helped by streetlights turns the two-page sheet and proceeds to fill in the details from Pathmasiri's responses. Nearby a policeman stops cars and other vehicles to enable two other members of the outdoor team - Priyanka Rajapakse (Colombo law undergraduate) and Thilanka Polgampola (also a Colombo law undergraduate) to take details of drivers and occupants.

Some motorists wave a small white paper indicating they have already

been counted and are allowed to proceed. There is no compulsion. The enumerators

ask motorists whether they would like to be  counted.

There is no opposition. The exercise is a pleasant one.

counted.

There is no opposition. The exercise is a pleasant one.

Pathmasiri, wearing a neatly pressed shirt and shorts, doesn't look like a homeless person. He is content with his surroundings and lifestyle. "We have lived on the street for more than five years. I don't see any other lifestyle for me and my family," he says.

But the fruit-seller who earns about 200-300 rupees a day has one goal - to ensure his children get the education that he didn't have. "My two bigger girls, nine and five years go to Vihara Maha Devi school near Maradana. I want them to study and be something in life," he says, wiping away a tear.

While the 25-point questionnaire of the Census Department was filled by enumerators during visits to households in an earlier phase of the census, details of the homeless and street people are being taken for the first time on July 17. It is the outdoor team's responsibility to collect all these details while enumerators visiting homes only count the inmates.

In that sense, Manawaduge and others in the outdoor team assigned to the Town Hall area, to collect details plus count the homeless people and others living on the streets, had a bigger task. "I don't think so. Enumerators involved in all three phases had a bigger job to do while this is the first time we are taking part in the census," the university student says as we walk past the Dewatagaha mosque and head towards a group of people sleeping on the pavement.

Next it is the turn of U. L. Samson, a fruit-seller from Galle district who occasionally lives on the street near the Vihara Maha Devi park where most of his sales take place. "I now live in Kotte with my family, but sometimes sleep here," he says pointing to some sheets placed on the pavement under the huge canopy of a Mara tree.

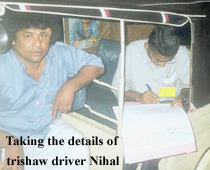

As Samson's details are taken down by Manawaduge, others among whom are many beggars-line up eagerly to speak to the census-taker. But before the young undergraduate can move to the next person in the line, a trishaw pulls up. "Sir, sir, apith gun-de ko,"_ pleads the plump, middle-aged driver.

Nihal Shanta Perera is from Kotte and has driven trishaws for 20 years. He says the white slip given by enumerators would help show his children that "I have also been counted".

Unshaven and dressed in rags, Mendis Karunaratne is a cripple who frequents the Town Hall area hoping to collect a few coins from passers-by to buy a packet of rice. He is pushed around in a wheelchair by Nayakakande Baddegama.

Karunaratne willingly provides the information Manawaduge needs and even remembers his date of birth, like many other homeless people interviewed, contrary to accepted belief that beggars and the homeless are unlikely to remember such details.

Quite a few of the Town Hall residents are traders who go to their village during the Sinhala and Tamil New Year. Many are from decent backgrounds like Karunaratne's father who was a respected 'veda mahathaya' in a village near Balapitiya.

For instance, Mudiyansalage Wattegama is a pineapple seller whose father worked as a carpenter at the Colombo Port, many years ago. The family came to the capital from Akuressa near Matara in the 1970s and Wattegama went to a small Colombo school but never completed his education.

After a couple of stints in the village market and elsewhere, he settled down to selling fruits near the Town Hall. "No, I am not interested in going back to the village. I like it here. We are free and we are independent," he says.

Data on Colombo's homeless should provide some fascinating details for non-governmental agencies involved in helping street people and their families. It should also reinforce the research study on the beggar population done many years ago by eminent sociologist - Professor Nandasena Ratnapala who lived on the streets for three months, disguised as a beggar.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to