Beyond History’s horizon

This is a story about a land that had been, for many millennia before the beginning of History, an island. History was something recorded by man, to be told to other men. But the story of this land which we call “Home” begins far beyond the horizon of history. Before reading the narratives of historians we must understand and appreciate the elemental forces that formed this land: how she came into existence; how she came to be situated here, at the southernmost tip of India; and how, when and why she became an island.

For, it is these forces that built the stage upon which the historians’ stories were acted out, and their actors played their parts. History was always shaped by the fact that this country is an island, and not part of a mainland Asia.

We are justly proud that we have a recorded history spanning over 2500 years. But, what happened here before that? There were humans living in this land long before that, long before history was recorded. Hundreds of millions of years it took, for this island to be born, and she assumed her present shape and form only a scant 7000 years ago. So, what happened before that time, and how was this island born?

The birth of this land

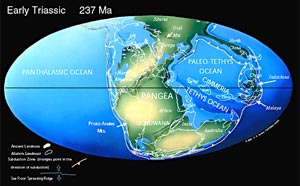

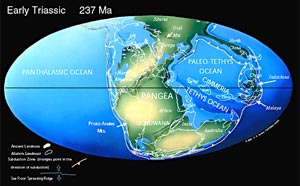

The story I relate begins long after the birth of the universe, of the solar system, and of the world we in which we live. It begins 255 million years ago when the world had already become a sphere of hard shell, or crust, of land (the “Lithosphere”) that floated atop a fiery liquid “magma”. By then, seas and oceans already existed, and most of this crust lay under their waters. All that was above the waters’ edge formed one block, a super-continent, which we have now named “Pangaea”.

It was enormous. Using modern place names for convenience we can describe it as stretching from the North Pole to the South Pole and from the Atlantic Ocean tip of South America in the west to China and Western Australia in the east. All of today’s continents and islands formed part of Pangaea. In shape, it was like a misshapen doughnut, with the western part of the ring broader than the eastern part. The “hole” in the doughnut was a huge inland ocean, the “Paleo-Tethys Ocean”. The landmass of Pangaea which surrounded the Paleo-Tethys Ocean was, itself, surrounded by a much larger ocean, the “Panthalassic Ocean” or “Panthalessa”.

We, too, were a part of Pangaea. Pangaea, itself, was composed of several (about 20) massive slabs of lithosphere called “Tectonic plates” (“plates”, for short), that floated on the liquid magma (molten basalt) layer below. The magma, constantly heated by Earth’s hot core, expands and flows upwards when heated, like any other liquid. This happens even now. When the pressure of the expansion reaches a critical point it presses upwards against the crust, splitting it and creating a crack, or “rift”, in the lithosphere through which magma oozes out.

|

There, when it encounters the coldness of the ocean depths, it solidifies into new crust. Over millions of years, this gradually builds up to be an undersea mountain range, which pushes the sundered ocean floor apart, and creates new “plates”. This mountain range is the 74,000 kilometre long “Mid Ocean Ridge,” found in every ocean, which denotes where Pangaea was split apart into different plates, different continents, and different oceans. Africa and South America split apart creating the Atlantic Ocean, just as Arabia and Africa created the Red Sea. These are but examples: but the tell-tale Mid Ocean Ridge – the largest and longest mountain chain in the world – can be found there.

Thus new crust was added, but the “Law of Conservation of Mass” does not permit the world to expand to accommodate it. Something has to “give”. So the older crust is destroyed and re-cycled. How? When two plates come together on a collision course “subduction” takes place: that is, the seafloor of one is forced under that of the other and driven into the magma, where it is melted down. The seafloor of the other plate ploughs over the first, closing the sea between them. The soil and rock of the subducted plate is scraped off and pile up, forming a new mountain chain. When two plates collide like this, major volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis occur. This is how the Himalayan Range was formed.

The voyage of the “Indian Plate”

Over millions of years, this pushing apart of the plates gradually separated them from Pangaea, and the various plates began voyaging, floating over the liquid magma and carrying portions of the crust on their backs. Taking the southern-most part of Pangaea, which we call “Antarctica” today, as the part that remained unmoved, the other plates moved away from it, and relative to each other – north, east, west. The plate carrying Africa-South America-India moved north. In time, South America moved away from that plate, creating the Atlantic Ocean.

Then, about 170-160 million years ago, a part of eastern Africa separated from Pangaea, and a new “Indian pla

Here, it collided with the much larger Eurasian Plate. Something had to give: in fact, more than one. The Indian plate subducted, and its seafloor was pushed under the Eurasian plate, 50 million years ago. The collision changed the shape of Eurasia, pushing that landmass 2,000 kilometres northwards. It pushed Mongolia and China to the east and Tibet to the north, raising it up by about eight kilometres above sea level and creating the Himalayan range. It is still taking place, though only at the rate of 5 centimetres a year. But the land that was to become Sri Lanka, did not push into India in the same way because both “Sri Lanka” and “India” were already parts of the same plate. So this land remains where it was when Madagascar dropped out: as the southernmost bit of the Indian plate.

This was not all. When the Indian plate moved north east and collided with Eurasia, the two landmasses compressed and closed up the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, the original “hole in the doughnut”. Trailing behind the Indian plate, were the waters of the much larger Panthalassic Ocean - which had once surrounded the whole of Pangaea – which then formed what we now call the “Indian Ocean”.

But where was the “island” we call Sri Lanka? She had once been a part of Pangaea, then part of the Indian plate and remained on it after Madagascar was left behind. (There are still a lot of similarities between the rocks of Africa, India, Madagascar and Sri Lanka, particularly regarding the building up of mountains about 550 million years ago.) In terms of plate tectonics and geology, Sri Lanka, however, remains a part of the Indian plate even today. In geological times, there was no island.

But today she is an island, and not part of Asia. How she can remain on the Indian plate and yet be an island can be a puzzle. The answer to that lies not in the earth (geology), but in the air, in climatic changes and sea level changes.

The birth and re-birth of an Island

Most of the world’s fresh water is trapped in the ice-caps around the geographical North and South Poles. There are two North Poles and two South Poles: the Geographical Poles and the Magnetic Poles. For this narrative, and simplicity, only the geographical poles, will be dealt with: the geographical Poles, shown at the “top” and “bottom” of the globe, that remain encased in ice today.

There had been periods in the earth’s History when there was no ice on earth: during much of the Earth’s history there had been no ice at the poles (“Greenhouse Earth”) when, tropical forests extended to the North Pole.

Alternating with these periods were Ice ages (“Snowball Earths”) with ice caps over the Poles. The ice cap over the North Pole and Greenland was formed only about 4 million years ago. Many reasons made these caps expand or recede, from time to time, alternating between “Glacial” and “Inter-glacial” periods. When the northern ice-cap expanded covering most of Europe, we had a glacial period. Then came an inter-glacial period, when the caps shrank in size. This cycle is repeated every 100,000 years, with 80% of each being a glacial period. There have been nine such cycles during the last one million years. We are, in fact, now living in one, and beginning to experience the shrinking of the ice cap.

How do the ice-caps expand or shrink? Since they are made of frozen water, water from the sea becomes ice when the world temperature drops. The ice-caps expand, the waters of the oceans reduce, sea-levels around shores recede, and land that was earlier under the sea comes above the new sea-level. Countries become larger and shallow water area become land. Temperatures drop world-wide. So does humidity. Ice ages are, therefore, dry ages.

|

| Tibetan plateu |

When the ice-caps melt, this process is reversed: sea-levels rise and lands along the sea-shore are submerged. Temperatures and humidity rise. Inter-glacial ages are, therefore, rich in vegetation. Scientists have mapped this up-and-down movement, and we now know what the sea-level was at different times in the past (compared to today’s level). We know, for instance, that only 18,000 years ago, the mean sea level was about 120 metres below present sea level.

It was this phenomenon that made Sri Lanka an island while yet remaining a part of the Indian plate. The Palk Strait, between north Sri Lanka and India, is a very shallow body of water. On our northwest is the Gulf of Mannar, between India and us, which is also comparatively shallow. Between these two bodies of water is a ridge, variously called “Adam’s Bridge”, “Ram Sethu” etc. But no man or god built a bridge there: it is a natural formation on the seafloor of the Indian plate. Whenever sea-levels drop just 12 metres below today’s levels (that is, during a glacial period) a large tract of seafloor, including that ridge will rise above the new sea-level, linking us with Asia.

The scientists’ record for the last 100,000 years shows that, during 80% of that time, Sri Lanka was part of the Asian landmass: there was no mere narrow ridge like “Adam’s bridge”, but a huge stretch of land many kilometres wide including the whole of what we call the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait. During these 100,000 years sea-levels rose high enough to make Sri Lanka an island only twice: first, about 120,000 years ago and second, about 7,500 years ago. We are living in the second, now. Since it takes a drop of only 12 metres to link us to Asia, it is easy to see that Sri Lanka was part of mainland Asia for 80% of the time.

All this we know from the work of modern scientists. But, apparently, there remained a folk memory of these events several centuries ago. The 13th century traveller, Marco Polo, has recorded a bit of that memory:

“……you come”, he says “to the island of Ceylon, which is in good sooth the best island of its size in the world. You must know that it has a compass of two thousand four hundred miles, but in old times it was greater still, for then it had a circuit of about three thousand and six hundred miles, as you will find it in the charts of the mariners of those seas. But the north wind there blows with such strength that it has caused the sea to submerge a large part of the island; and that is the reason why it is not so big now as it used to be. For you must know that, on the side where the north wind strikes, the island is very low and flat, insomuch that in approaching from board ship from the high seas you do not see the land till you are right upon it.”

Marco Polo’s inaccuracies have long been pointed out. Here, though, is one instance where what he had gathered does not vary much from 20th. century scientific research.

That is how Sri Lanka came to be an island, while being a part of the Indian Plate, wedged under the Eurasian Plate. And, being an island made her history what it is. But History – as we have noted – is man-made: so when did Man come into the picture? That is the subject of Part 2 – “The First Peoples”. |