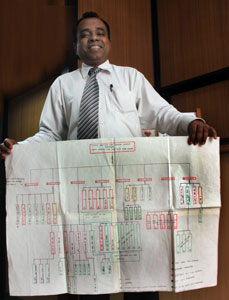

It was a few years ago that two brothers walked into the Human Genetics Unit of the Colombo Medical Faculty with a large rolled up flip-chart. Meticulously drawn on it were boxes in different colours.For Medical Geneticist Dr. Vajira H.W. Dissanayake that moment will be etched in his memory forever.

It was their family tree and all those marked as red boxes were dead, struck by a genetic disorder called Spino Cerebellar Ataxia, a gross lack of coordination of muscle movements. In four generations of a family, 28 members had succumbed, after having reached adulthood. Three of them had even taken their own lives when they developed symptoms possibly because it was so painful for them to live with the condition.

Not only cutting out the agony and sorrow of losing a loved one but also the massive expense incurred by both the family and the country in dealing with such an illness and what measures could be taken to pre-empt such deaths would all be possible if genetic testing were easily accessible, the Sunday Times understands.

As the world prepares to mark the International Rare Genetics Diseases Day (http://www.rarediseaseday.org/) which falls tomorrow, Dr. Dissanayake explained that such diseases or disorders are caused by abnormalities in the genetic material of a person. It’s everything to do with the genes, which are passed down to a person from his father and mother and determine specific characteristics, says Dr. Dissanayake, adding that although there are lots of rare genetic disorders, thousands of them around, they are individually rare – fewer than one person in 200,000 people suffer from them.

|

| Newborns can be screened for genetic conditions a few days

after birth using a blood spot taken from a heel-prick |

But when all those are put together they account for a considerable number of morbidities (illnesses) and mortality (deaths).

The Sunday Times highlighted two such patients recently – Bubble Baby Sanjana Praveen Shivanka who is suffering from Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Syndrome (SCID) whom our readers helped to send to India for a life-saving bone marrow transplantation and Thilina who is afflicted with Franconi Anaemia. Since then two more children with immunodeficiency syndromes – one with SCID and another with Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency have also been found, it is learnt.

Dr. Dissanayake cites thalassaemia as an example. There are about 2,000 afflicted with this disease in Sri Lanka and for each one the annual treatment cost estimates range from Rs. 750,000 to Rs. 1 million. “Even with 5% of the annual health budget being expended on these 2,000 what is the outcome,” he asks, answering that they lead a poor life, they are not productive, they die young, the families suffer and are stigmatized.

That’s just one rare genetic disorder in this country. We have no estimated numbers for many others, according to this Medical Geneticist.

Dr. Dissanayake recalls the clinic for neurogenetic disorders for adults conducted by the Human Genetics Unit at the Institute of Neurology, National Hospital, Colombo to which came the two brothers armed with the family tree.

“The first year we saw 50 families. There were 189 affected people in those families and 385 unaffected people who had the potential to manifest the disease later in life.This is just one year’s data for one clinic. What of the situation out there, with no data,” he queries, arguing that with the aim of the health service being to create a healthy population and the country rightly boasting of huge milestones in reducing both infant (in 2009 it was 12.7%) and maternal mortality rates, beating other countries in the region and being on par with the developed world, the need is to provide screening for genetic disorders.

After such testing, people will benefit by counselling, advice on future risks, marriage and having healthy babies or undergoing alternative forms of reproduction, according to Dr. Dissanayake.

Otherwise, vulnerable people will be drawn into a vortex of genetic disorders, hospital visits, and a cycle which will lead them to penury. “Those assailed by inherited disorders are dismally poor because they have invested all their family resources to get out of this health trap but failed.”

|

| Dr. Dissanayake holds up human genetic chart. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara |

Explaining that the Human Genetics Unit has only limited facilities for genetic testing, he stresses that as there are doctors and scientists trained in this field a National Screening Programme is a necessity.

The unit provides consultation free of charge but is compelled to ask those seeking help to pay for the tests, it is learnt.

Urging support and donations to expand the services provided by the unit to which about 1,500 come every year, Dr. Dissanayake says like the two brothers who walked in with a family tree full of relatives felled by Ataxia, there are many across the country crying for help.

Some genetic testing done here

There is hope for a large group that needs to undergo genetic testing for Inborn Errors of Metabolism, the Sunday Times understands with the Human Genetics Unit introducing screening for three disorders this week.

Earlier such testing was not available in Sri Lanka with specimens having to be sent to India, says Dr. Vajira Dissanayake pointing out that of 55 high-risk samples sent there in the last six months 20% came positive.

Metabolic disorders occur when a genetic defect results in the production of a defective enzyme which is required to make energy from the food we eat.

Seeing the vital need for such testing the Human Genetics Unit has now introduced metabolic screening at a minimal cost of Rs. 1,500 for Congenital Hypothyroidism (thyroid hormone deficiency present at birth), Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (disorders of the adrenal gland) and G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme which protects red blood cells).

Screening for the entire spectrum of inborn errors of metabolism covering over 100 rare disorders is also available at a higher fee.

(For more information please contact the Human Genetics Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Kynsey Road, Colombo 8; Phone: 011-2689545; Fax: 011-2689979 or email: office@hgucolombo.org. Donations in the form of cheques drawn in favour of ‘University of Colombo’ may be sent to: The Director, Human Genetics Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo) |