Christopher Columbus never visited the country named after him; it was Spaniard Alonso de Ojeda, who arrived at the mouth of the Orinoco River in 1499 CE. The wealth of the local Amerindians, their intricate gold jewellery and stories about inland treasures drove Spanish conquest into the interior.

In one fantastic story, the king of the Muiscas of Bacatá, the Zipa, would ritually float into the middle of the Lake Guatavita, strip and be dusted with gold. He would offer great treasures to the sacred waters and then jump in himself.

The story of El Dorado (‘the golden one’) retold with elements of many other tales illuminated a mythical empire with mountains of gold. While the conquistadors captured riches for the Spanish Crown, they never found their City of Gold. In contrast to the unending quest for love, riches or happiness of El Dorado, is Serendipity, unexpectedly finding riches, beauty and serenity.

|

| On board a chiva: Music for the ride |

|

| Cathedral de Sal, Zipaquirá |

Englishman Horace Walpole coined the term ‘serendipity’ in 1754 referring to the Persian fairy tale “The Three Princes of Serendip”.

Serendip is the Persian name for Sri Lanka. Coming from this island nation, I had an insightful trip to Colombia in October 2009. Serendip is a derivation of the Sanskrit term Swarnadip.

The roots of this word, swarna (gold) and dvipa (island) bring us full circle to ‘the golden one’. Contrast blurs to similarity.

There are many parallels between Colombia and Sri Lanka. Tropical countries with warm people, delectable cuisine and a colonial heritage, both countries are at turning points in wars that ravaged the countries for a generation or more. While the causes and the development of the conflicts differ, much can be gained by exploring the historical parallels of uneven development and political intolerance that led to violent unrest.

From positions that seemed intractable the governments of Sri Lanka and Colombia have made great progress overcoming rebel groups and reclaiming territory recently.

This territorial integrity is a positive starting point for social development and capitalist enterprise; yet lasting peace requires addressing the underlying needs of the people, to ensure basic freedoms for all citizens to live and prosper.

Simon Bolivar’s

independence struggle

Simon Bolivar’s independence struggle resulted in the formation of Gran Colombia in 1819. Even after Venezuela and Ecuador seceded in 1830, the centralist forces of the Conservative Party, were fiercely opposed by the federalist forces of the Liberal Party. There were a series of insurrections and civil wars between these parties. Later La Violencia (1948-1958) killed 300,000 people. In the aftermath, the leaders of the two parties agreed in 1956-57 to alternate four-year terms of ruling the country for the next 16 years. While this arrangement provided stability, the inability for members of alternative political parties to participate in the electoral process or become public employees effectively forced dissenting voices into the darkness of guerrilla insurrection.

As the Cold War swept the world in the 1940s and 1950s, Colombia, with a colonial legacy of poor land distribution and impoverished peasants, bred armed leftist groups plotting against what they deemed a self-serving and corrupt establishment. The landowners and business-cartel lords raised their own paramilitaries leading to four decades of armed conflict. Leftist forces began farming and selling cocaine to support the insurrection, but eventually armed guerrilla warfare was conducted to gain access to the cocaine trade.

FARC: Largest insurgent group

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) formed in 1964 was the largest of the insurgent groups. Attacking civilians (especially indigenous populations) and government establishments, recruiting children, taking hostages for ransom and political leverage, and planting landmines are some of the tactics that branded the group a ‘terrorist organization’ in the USA, Canada and Europe. Any validity to the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary ideology was lost in the cruel economics of cocaine versus human life.

|

| Gonzales Forero Square, Zipaquira |

The right-wing paramilitaries joined the cocaine trade in 1980s. These groups formed the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) in 1997. As successive governments failed to unite the country , a generation of people grew up under guerrilla rule much like in Northern Sri Lanka.

In today’s post-war Sri Lanka, where secessionist rebels have been militarily defeated and land they held has been retaken by the government, examining the causes of war will help formulate the way forward. Since the twins of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism and Tamil nationalism grew up reinforcing each other, both have to be diffused to build a united nation.

Conquest versus freedom

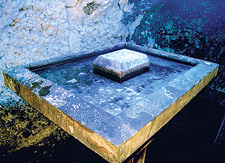

The conquistadors of Colombia did not realize that the Muisca Indians acquired their gold by bartering emeralds and salt extracted regionally. {In the Savannah of Bacatá, present elevation of 2.6km above sea-level, salt came from the earth itself.

When the Andes mountain range was forming during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, a saline lake evaporated all its water and the salt was trapped underground. The Muisca used water to melt portions of the deposit and extract the valuable commodity} from 5th century BCE. Progressively larger operations have mined this massive underground ore body of rock salt, and today a modern mine continues underground.

I took a bus from the capital Bogotá to Zipaquirá – ‘the land of the Zipa’ – at the foot of the salt mountain. In the 1930s, the miners had carved a sanctuary, to pray for protection during their work in the darkness. A bigger cathedral was built for the public in the 1950s and a newer one in 1995. I got off the bus, without the ability to speak Spanish.

However a Colombian couple, who got off the bus with me, offered a ride in the cab they hired. Colombians are proud of their beautiful country and go out of the way to be hospitable to visitors, much like Sri Lankans.

About 95% of Colombia’s population is Christian and a vast majority Roman Catholic. While many cathedrals beautify the countryside, I saw no signs of state involvement in religion. The Colombian Constitution of 1991 removed the Roman Catholic Church from being the state church.

This was a contrast to my experience landing in Colombo in August 2009 when I was surprised to see a Buddha statue before the immigration counter at the airport. While I identify as a Buddhist, along with 70% of Sri Lankans, I wonder how excluded followers of Hinduism (15% of Sri Lankans), Islam or Christianity (7.5% each) feel at the sight.

Sri Lanka provides ample religious freedoms and has a culture of tolerance and respect. However, despite the fact that Buddhist monks were accepted as advisors to the ancient Sinhala kingdoms, the Buddhist clergy’s increasing involvement and influence in modern Sri Lankan politics does not help a polarized populace unite under a secular democracy.

What’s so civil about war anyway?

Colombia’s 2002 election of President Álvaro Uribe and Sri Lanka’s election of President Mahinda Rajapaksa were turning points for the two countries as these leaders have maintained hard-line stances on security, strengthened the military and fought for unification. Both leaders have been criticized for their tactics, but both have won decisive victories. With the destruction of the top LTTE leadership, Asia’s longest civil war was declared over in May 2009 . South America’s longest-running armed-conflict continues in remote areas and around the Colombian borders with Venezuela and Ecuador, though most of the high population density areas are safe.

Getting on the fun bus

Colombians used to travel between cities on chivas, buses with elaborately painted wooden bodies. When in Medellín, my hosts organized an enjoyable chiva tour. A band of musicians in the backseat played popular tunes; our Colombian friends sang; the whole bus clapped along – another similarity to Sri Lanka, where no group trip is complete without singing, clapping and banging on anything that is available.

Both the governments of Colombia and Sri Lanka propose ‘development’ as the cure to all woes. While roads, running water and electricity will help improve quality of life in former war zones, successful plans have to ensure equal access to opportunities and empower local institutions.

In 1956 Colombia limited political expression to the Liberals and Conservatives. Around the same time, Sri Lankan politicians tried to dislodge the Tamil-speaking population from the state apparatus. These exclusionary developments, coupled with uneven opportunity distribution and narrow-minded nationalism led to decades of war.

Today, both countries have golden opportunities to address the root causes of conflict with intelligent dialogue incorporating dissenting voices, rather than gloat in military victories without building political cohesion. Let us ensure that everyone can get on the fun bus, rather than leaving some by the roadside waiting to topple the next. |