| If you’ve never met her before, watching Manuka Wijesinghe read from Theravada Man is as good an introduction to the author as one could desire. Exuberant and outgoing, Manuka is comfortable in the limelight, embracing a number of roles including those of painter, dancer, poet, pranic healer and actress.

With the launch of her second book, she reprises another familiar part, that of a satirist. Part mystery, part comedy, part philosophical exposition, her new novel follows the life of a humble iskolemahaththaya in rural Sri Lanka. She uses his life, in its quiet rural setting, to explore how living with Theravada Buddhism can affect one’s most intimate relationships. If the results are sometimes decidedly critical of Theravada philosophy, it is because Manuka herself has her reservations.

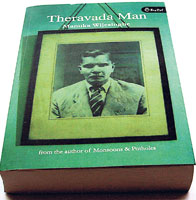

“This direness, this repression, it is our tradition,” says Manuka frankly. The photograph of the stern, elderly man that graces the cover of her book is of her paternal grandfather, she says. A school teacher, he earned Rs.29 a month and gradually acquired land as he grew older. “It was a very correct existence, very much dharma abiding,” says the author.

Researching the book has given her some degree of sympathy with her ancestor, a level of understanding she believes she would not have achieved as a more immature writer. Still, impressions garnered as a young girl hold sway. Explaining that her mother’s side of the family were quite different and altogether more relaxed, she says of her childhood, “I was caught in between because I quite liked that madness and the piety got on my nerves.”

The comment is vintage Manuka. Often shockingly frank, she never seems to pause for a breath between sentences. Her laughter rings out frequently, and any conversation with her is likely to traverse a range of subjects from the origins of the Sinhala race to the challenges of adapting to life with teenagers. She refuses to stay still long enough for any moss to grow on her, and not just intellectually. Though our coffee date begins early enough for me, I find Manuka has already been up for hours. Often she uses the quiet, dark hours to write, a schedule she has stuck doggedly to through motherhood, travel across continents and personal crisis.

She has had to juggle all three while writing Theravada Man, and says that she managed in part because “you just project your emotions into the book.” However, her character, the iskolemahaththaya, seems to have more difficulty dealing with his inconvenient emotions. Manuka has the staid misogynist struggle with desire, and seems to delight in pitting his faith in Theravada Buddhism and the British education system against astrology, numerology and myth. She chronicles the resulting fallout with humour, providing an often idiosyncratic historical context to the story.

|

| Manuka:

Woman

of many roles |

In preparation for the novel, Manuka read extensively. “This book has many threads...I started studying Sanskrit first, because I wanted to understand this country before the advent of Buddhism,” she says. Much of this was accomplished while in Germany. “I began to see the country with greater clarity from outside, I observed it more objectively.” When she finally put pen to paper, nothing would be spared her eviscerating pen, not the Mahavamsa; not British colonial rule nor contemporary Sri Lankan politics; not Dutugemunu or S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and most especially not the rise of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism.

As a student of Gabriel García Márquez’s magical realism, Manuka enhances both fact and fiction with her own brand of inherently comic mysticism. Her over-the-top, tongue in cheek account of the British OIC’s visit to the village in pursuit of a murderer, for instance, may have you in gales of laughter as may the many encounters between astrologer and the iskolemahaththaya. Humour, for Manuka, seems to be the sharpest of a writer’s tools, and in common with her close friend, playwright Indu Dharmasena, (who often reads with her) she declares that she can find “the comic side in anything!”

Today, Manuka seems to be writer almost by chance. In search of the best medium for self - expression she has in the past turned to a number of other conduits. “My first medium was and is poetry,” she says explaining that she first began composing poems as a student. “I don’t write it anymore for the simple reason that nobody understands what you’re saying.” She would also become briefly enraptured by painting and remembers first beginning to paint during the long curfew nights, when left alone with her sprawling canvas in her living room, she would create angry, flamboyant paintings loaded with symbolism. However, her need to communicate what she was feeling clearly would finally lead her to prose and her well received debut, Monsoons and Potholes.

She brings the experience of a colourful life, spent travelling to places as different as Nigeria and Germany for her work. Though she speaks German (and Spanish) fluently, it is clear that it is Sri Lanka she calls home. When I meet her, she is back in Colombo for one of her frequent visits. Though she’s already at work on her next book, she says “I’m not a professional writer. I’ll probably give up at some point in my life.

” Apparently astrologers had long predicted she would learn medicine, and of late she has proved them right by spending a lot of time mastering pranic healing, acupuncture and homeopathy.

Will she ever settle down to one thing? “The world we live in has many aspects.

How can I confine myself to one?” asks the astrologer in her book, and that pithy answer seems to best encapsulate Manuka’s own philosophy. |