By Dr. Prasad Mahindarathne

Organic agriculture claims to be the fastest-growing sector in world agriculture and it is not at all a distant or novel thing to our country. With the recent policy decision banning the importation of inorganic fertilizers by the present government, this has become the most discussed topic of the day.

The purpose of this article is to shed light on the key scientific and essential economic aspects of organic agriculture that would enable readers to make a balanced and objective assessment.

How big is the world Organic Agriculture sector?

Organic Agriculture is reputed to be the fastest-growing agriculture-based industry in the world. The Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) and the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) have been conducting an annual survey of organic agriculture since 1999 in which they collect data on the extent of certified organic farmlands and the size of the organic market in the world. According to the FiBL-IFOAM survey-2021, the market for organic products has grown dramatically reaching to USD 130 billion mark in 2019 and there is a similar increase in organically managed farmland around the world.

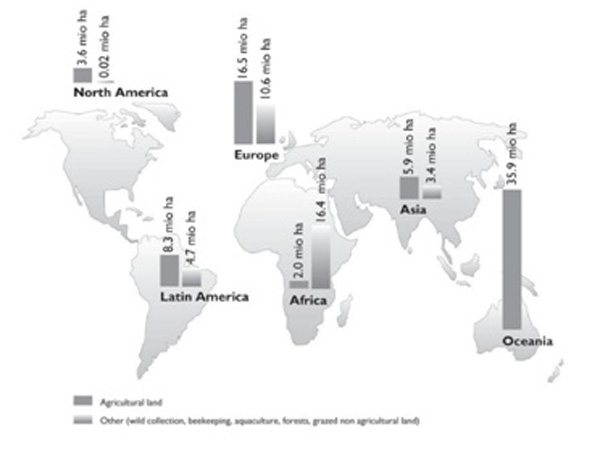

As the survey reported, 72.3 million hectares (which was 1.5% of the world’s farmland) were under organic farmland that was occupied by 3.1 million organic farmers in 2019. The survey report further revealed that the growth rate of organic farmland since 1999 was more than 555%. By 2019, Australia (35.7 million hectares), Argentina (3.6 million hectares), and Spain (2.4. million hectares) were the top three countries with the largest areas of organic farmland.

With regard to the number of organic farmers, India (1.36 million), Uganda (0.21 million), and Ethiopia (0.203 million) had come to the top of the list. When considering the top three organic markets in the world, the USA (USD 54. 5 billion), Germany (USD 14. 6 billion), and France (USD 13.75 billion) were at the top of the list.

|

| Organic Agricultural land and non-organic agricultural land in 2019 Source: The FiBL-IFOAM Survey 2021 |

Referring to the survey, the contribution of Asia to the world organic farmland was about 5.9 million hectares (8.2 % of the global share) where the leading contributors were India (2.3 million hectares) and China (2.2 million hectares). And India (5th) and China (7th) were among the top ten countries in the world with the largest areas of organic farmlands. Even though the contribution to the global share is comparatively low, Asia is in a significant position with respect to the 10-year growth rate of organic land extent, which is as high as 140.5% (the world 10-year growth rate is only 102 %).

Where does the Organic Agriculture stand in Sri Lanka?

Organic Agriculture per se is not a new concept to Sri Lanka. It has been there for centuries and our farmer ancestors had been able to make our country self-sufficient in rice by practising organic agriculture and even the surpluses had been exported as reported in historical documents. During the reign of King Parakrama Bahu, Sri Lanka was known as the granary of the east. However, things have changed dramatically in the last several decades and the use of synthetic-inorganic agrochemicals has become rampant due to inevitable demand for increased production and productivity.

In Sri Lanka, organic farming practices with proper standards were initiated in 1979 with the initiative of a non-government organization, namely, "Gami Seva Sevana". As stated by the FiBL-IFOAM survey, in 2019, Sri Lanka had about 70,436 hectares of organic farmlands (2.5% of contribution to the global organic land extent) which was about 2% of the total farmland of the country.

The survey further revealed that the one-year growth rate of organic farmland of the country was minus 8.7%, yet the ten-year growth rate has been remarkably high as 216%. This gives a clear reflection about the increased interest of the country over organic agriculture. According to the local sources, currently Sri Lanka has about 9000 organic farmers, 225 organic processors and more than 300 organic exports including more than 200 certified exports.

At present, a number of Sri Lankan companies have been engaged in Organic Agriculture to different scales where their major market base is the international market. The main certified organic products are tea, desiccated coconut, cashew nuts, spices (cinnamon, cardamom, nutmeg, pepper, clove, ginger), fruit (mango, papaya, passion fruit), and herbs (citronella, lemongrass). Most of these organic products are exported to Europe, Japan, and Australia. At the same time, several organic products such as tea, spices, fruits, and vegetables are increasingly being sold in major local supermarkets. With the expansion of export and local markets, national-level standards for organic products have been a long-felt need.

Meanwhile, Lanka Organic Agriculture Movement (LOAM) was created in 1994 with a group of like-minded NGO activists, planters, scientists, and environmental activists. This was considered as the apex body of organic movement of the country. The primary objectives of LOAM were to promote organic agriculture, establish, improve and maintain standards for organic agriculture, and create awareness of organic products among the people of Sri Lanka.

LOAM played a major role in policy development; in preparation of organic agriculture guidelines in 2005 and developing standards for organic agriculture in 2007. Consequently, LOAM has successfully influenced the government to come up with a national policy for the organic agriculture sector. Subsequently, the National Organic Control Unit (NOCU) was established in 2014 under the Export Development Board (EDB) Act to facilitate all matters connected with the export of organic products. Hence, the mandate of NOCU is to ensure the credibility and safeguard the image of Sri Lankan organic produce by ensuring that the term “Organic” is used only for those products that are produced according to the National Standards for Organic Production and Processing.

At the same time, seven foreign Certification Agencies are operating in Sri Lanka namely, Control Union (SKAL, Netherlands), NASAA (Australia), Naturland (Germany), Institute for Market Ecology-IMO (Switzerland), Eco-Cert (Switzerland), Organic Farmers and Growers Ltd. (United Kingdom) and Demeter and BioSuisse (Switzerland).

What is Organic Agriculture?

Organic Agriculture is based upon traditional sustainable agriculture, farmers’ innovations, and the results of scientific research. Organic farming practices are embedded in local cultures and their ethical values and beliefs. Thus, Organic Agriculture (OA) has been subjected to a wide variety of definitions merely due to its complex and comprehensive nature.

The Food and Agriculture Association (FAO) and Codex Alimentarius Commission of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1999 published their definition of organic agriculture as “a holistic production management system which promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity. It emphasizes the use of management practices in preference to the use of off-farm inputs, taking into account that regional conditions require locally adapted systems. This is accomplished by using, where possible, agronomic, biological, and mechanical methods, as opposed to using synthetic materials, to fulfil any specific function within the system”.

The International Federation of Organic Movement (IFOAM) is considered to be the umbrella organization that guides and unifies the Organic Agriculture movement of the world. It has a membership of about 700 organizations (research, certification, education, and growers). IFOAM was established to harmonize standards developed by private/voluntary sector bodies. IFOAM sets minimum standards, which provide certification programs with a basis for developing detailed local production standards. IFOAM standards have been a major influence on the development of national laws regulating organic farming, including Regulation 2092/91 and the Codex Alimentarius guidelines which were set up by FAO and WHO. At present, IFOAM provides a forum, publishes basic standards, and awards its accreditation to organizations and their production standards through the IFOAM Accreditation Program (IAP).

According to the IFOAM definition, organic farming is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic Agriculture combines tradition, innovation, and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and good quality of life for all involved.

Both the above two recognized definitions demarcate the territory or the scope of organic farming in a very wider perspective. So, organic farming by virtue goes well beyond the restrictions to use synthetic inputs in the production and processing activities. It essentially urges to take all possible measures to nurture the ecosystem while enhancing the quality of life of all stakeholders.

What are the governing principles of Organic Agriculture?

Traditional sustainable agriculture originated on the local knowledge has been in practice for centuries in many developing countries and such systems still today provide locally adaptable solutions to many of the problems in contemporary agriculture. Also in the developed world, in Europe and Australia, organic agriculture has been originated from the local knowledge and experience of farmers. However, with the widespread popularity and increased commercialization of organic agriculture, concepts, principles, practices, and norms related to organic agriculture have started to evolve, streamline and standardize over the last couple of decades.

IFOAM in 2009 has laid down four principles of organic agriculture; the principle of health, the principle of ecology, the principle of fairness, and the principle of care.

Principle of Health: Organic Agriculture should sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal, human and planet as one and indivisible. This principle points out that the health of individuals and communities cannot be separated from the health of ecosystems - healthy soils produce healthy crops that foster the health of animals and people. Health is the wholeness and integrity of living systems. It is not simply the absence of illness, but the maintenance of physical, mental, social and ecological well-being. Immunity, resilience and regeneration are key characteristics of health. The role of Organic Agriculture, whether in farming, processing, distribution, or consumption, is to sustain and enhance the health of ecosystems and organisms from the smallest in the soil to human beings. In particular, Organic Agriculture is intended to produce high quality, nutritious food that contributes to preventive health care and well-being. In view of this it should avoid the use of fertilizers, pesticides, animal drugs and food additives that may have adverse health effects.

Principle of Ecology: Organic Agriculture should be based on living ecological systems and cycles, work with them, emulate them and help sustain them. It states that production is to be based on ecological processes, and recycling. Nourishment and well-being are achieved through the ecology of the specific production environment. For example, in the case of crops, this is the living soil; for animals, it is the farm ecosystem; for fish and marine organisms, the aquatic environment. Organic Agriculture should attain ecological balance through the design of farming systems, establishment of habitats, and maintenance of genetic and agricultural diversity. Those who produce, process, trade, or consume organic products should protect and benefit the common environment including landscapes, climate, habitats, biodiversity, air, and water.

Principle of Fairness:Organic Agriculture should build on relationships that ensure fairness with regard to the common environment and life opportunities. This principle emphasizes that those involved in Organic Agriculture should conduct human relationships in a manner that ensures fairness at all levels and to all parties - farmers, workers, processors, distributors, traders, and consumers. Organic Agriculture should provide everyone involved with a good quality of life, and contribute to food sovereignty and reduction of poverty. It aims to produce a sufficient supply of good quality food and other products. This principle insists that animals should be provided with the conditions and opportunities of life that accord with their physiology, natural behaviour, and well-being.

Principle of Care:Organic Agriculture should be managed in a precautionary and responsible manner to protect the health and well-being of current and future generations and the environment. Organic Agriculture is a living and dynamic system that responds to internal and external demands and conditions. Practitioners of Organic Agriculture can enhance efficiency and increase productivity, but this should not be at the risk of jeopardizing health and well-being. Consequently, new technologies need to be assessed and existing methods reviewed. Given the incomplete understanding of ecosystems and agriculture, care must be taken. This principle states that precaution and responsibility are the key concerns in management, development, and technology choices in Organic Agriculture.

Science is necessary to ensure that Organic Agriculture is healthy, safe, and ecologically sound. However, scientific knowledge alone is not sufficient. Practical experience, accumulated wisdom, and traditional and indigenous knowledge offer valid solutions, tested by time. Organic Agriculture should prevent significant risks by adopting appropriate technologies and rejecting unpredictable ones, such as genetic engineering. Decisions should reflect the values and needs of all who might be affected, through transparent and participatory processes.

What are the benefits and opportunities?

Organic Agriculture is highly capable of bringing out a range of benefits in socio-cultural, ecological, and economical terms. Many studies have been carried out to assess the benefits of organic agriculture at different setups.

The article “10 reasons why organic agriculture can feed the world” written by Ed Hamer and Mark Anslow to the Ecologist Journal in 2008 states:

Yield: Switching to organic farming would have different effects according to where in the world you live and how you currently farm. Studies show that the less-industrialized world stands to benefit the most.

Energy: Currently, we use around 10 calories of fossil energy to produce one calorie of food energy. Studies over the past three years have shown that, on average, organically grown crops use 25 percent less energy than their chemical cousins.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change: Despite organic farming’s low-energy methods, it is not in reducing demand for power that the techniques stand to make the biggest savings in greenhouse gas emissions.

Water Use: Agriculture is officially the thirstiest industry on the planet, consuming a staggering 72 percent of all global freshwater at a time when the UN says 80 percent of our water supplies are being overexploited. Organic Agriculture is different. Due to its emphasis on healthy soil structure, organic farming avoids many of the problems associated with compaction, erosion, salinization and soil degradation, which are prevalent in intensive systems.

Localization: The organic movement was born out of a commitment to provide local food for local people, and so it is logical that organic marketing encourages localization through veg boxes, farm shops and stalls.

Pesticides: According to the WHO, there are an estimated 20,000 accidental deaths worldwide each year from pesticide exposure and poisoning. Further, the increased dependence on pesticides has resulted in an array of repercussions, including pest resistance, disease susceptibility, loss of natural biological controls and reduced nutrient-cycling. Accordingly, organic agriculture provides unprecedented solutions to the above problems.

Ecosystem Impact: Organic farms actively encourage biodiversity in order to maintain soil fertility and aid natural pest control. Organic production systems are designed to respect the balance observed in our natural ecosystems. It is widely accepted that controlling or suppressing one element of wildlife, even if it is a pest, will have unpredictable impacts on the rest of the food chain. Instead, organic producers regard a healthy ecosystem as essential to a healthy farm, rather than a barrier to production.

Nutritional Benefits: Studies have found significantly higher levels of vitamins as well as polyphenols and antioxidants in organic fruit and veg, all of which are thought to play a role in cancer prevention within the body.

Seeds are not simply a source of food: they are living testimony to more than 10,000 years of agricultural domestication. Tragically, however, they are a resource that has suffered unprecedented neglect. The FAO estimates that 75 percent of the genetic diversity of agricultural crops has been lost over the past 100 years. Seed-saving and the development of local varieties must become a key component of organic farming, giving crops the potential to evolve in response to what could be rapidly changing climatic conditions. This will help agriculture keeps pace with climate change in the field, rather than in the laboratory.

Job Creation: By its nature, organic production relies on labour-intensive management practices. Smaller, more diverse farming systems require a level of husbandry that is simply uneconomical at any other scale. Organic crops and livestock also demand specialist knowledge and regular monitoring in the absence of agrochemical controls.

The economic perspective

Without exception, economics plays a vital role in determining the success and sustainability of organic agriculture. A bundle of benefits offered by organic agriculture is overwhelmingly accepted, yet practising organic agriculture within an economically viable context is imperative when considering its overall sustainability. At the same time, the economic analysis of organic agriculture should be done in a broader perspective since it generates wider economic benefits at different levels in different time horizons.

Researchers suggested carrying out economic analysis of organic agriculture at three levels; economics of OA at the farm level (micro-level), the economics of OA at the regional or national level (macro-level), and international analysis (global level). The micro-level analysis compares the socio-economic parameters between organic and non-organic farms or analysis economic returns based on research plot yield data or modeling comparison of organic and conventional farms. In macroeconomic analysis, on top of assessing the economic productivity and profitability of OA, it also analyses the implication that the adoption of organic farming will have on the quality of life of present and future generations, on the agricultural production, on supply of agricultural products to the level of self-sufficiency, on export, price of products, and synthetic inputs production and input price. Then, the international level analysis encompasses the impacts of organic agriculture on international trade.

How to analyse the profitability of organic agriculture

Profitability describes the degree to which a business or an activity yields profit or financial gain. Thus, profit is the most common and accepted indicator for the success of economic activity. Profit generally calculates as the difference between the amount earned and the amount spent in buying, operating, or producing something. Accordingly, organic farming can be considered economically profitable if the returns to the production factors used to exceed their opportunity cost. On top of the many other benefits offered, profitability is one of the critical factors for farmers adopting organic agriculture.

Numerous research studies carried out all over the world to enquire the profitability of organic agriculture have found that:

What are the challenges ahead?

Organic agriculture has gained considerable attention all over the world. The advocates see it as a panacea whereas the challengers claim it as ideological nonsense. Without falling into either extreme, a fair assessment of organic agriculture would help to identify pertinent challenges faced by those involved.

Moving forward

Australia is a country with an increased interest in organic agriculture and as a single country, it has the highest organic farmland extent of more than 35.7 million hectares (which is about 26 percent of their total farmlands) which accounts for about 50 percent of the world organic farmland extent. Consequently, numerous research and development work on organic agriculture has been carried out in Australia not only on technology and production-related aspects but also on economic and social aspects.

Reviewing the results of some studies carried out in Australia, Vogl, Hass, and Kummer (2005) raised three fundamental questions that should be answered to promote organic agriculture on large scale. Those are;

When considered as a whole, it is conspicuous that there is a dire need and huge potential for organic agriculture, yet it needs a very comprehensive and well-organized approach capable of lessening the blockades and challenges of organic agriculture. Therefore, a comprehensive roadmap needs to be developed for organic agriculture promotion in the country with short-term, medium-term, and long-term objectives.

In such an endeavour, it will be essential to come up with a pragmatic plan, learning from international and national experiences, deploying a scientific approach, and obtaining the service of international and national experts.

(Theauthor is a Senior Lecturer attached to the Faculty of Animal Science & Export Agriculture, Uva Wellassa University. He obtained his bachelor's degree in Agriculture and Master's degree in Business Administration (MBA) from the University of Peradeniya and doctoral degree (Ph.D.) from Dalian University of Technology, China. He has been engaged in undergraduate teaching and research in agribusiness management, agriculture entrepreneurship, agriculture information management, and technology dissemination)

Leave Comments