Preamble

At the outset, I would like to thank the Director General and the staff of the National Planning Department of the Ministry of Finance, Economic Stabilisation and National Policies for inviting me to this important occasion of launching of “National Social Protection Policy of Sri Lanka”. Whilst this policy framework is a milestone in social protection and well-being of the people of Sri Lanka going forward, I thought it is important to share my views on “Shaping the Future: Policies for Dynamic Growth towards Improving Social Protection and Wellbeing of the People“, considering the fact that Sri Lanka is at crossroads at present towards responsible macro-fiscal management and governance.

A robust social welfare structure has been engrained in Sri Lanka’s socio-political fabric even prior to independence. A long history of universal free education and universal free healthcare has resulted in Sri Lanka’s human development surpassing that of regional and income peers over many decades. In fact a key goal of economic development, if not the most important goal of economic development, is to uplift the well-being of the population.

The long-standing commitment of successive governments to public welfare has enabled Sri Lanka’s life expectancy at birth to reach 72 years as early as 1990, well ahead of most income and regional peers. Sri Lanka’s infant mortality in 2019 was 6 per 1,000 live births, still one of the lowest among peers. Secondary school enrolment was 96% in 2019, well ahead of regional peers. Sri Lanka also leads among access to sanitation in the region and has one of the highest levels of access to electricity.

These indicators provide a stark contrast to the popular public sentiment that no progress has been made in 76 years since independence. The well-being of Sri Lankans, as reflected in human development indicators, far surpassed those of countries with similar levels of income over several years. This is not to say that things are perfect and that nothing further needs to be done. For instance, while access to education is excellent, the quality of education delivery has fallen short of requirements to compete in the modern economy. The same applies to healthcare, public transport, and other public services.

The fault of successive governments has been that this public expenditure including on welfare, which in fact extended to government provided jobs and pensions resulting in the public sector expanding to over 1.4 million employees, has not been backed up by domestic revenue mobilisation. Successive governments have been reluctant to build a sustainable tax base. Some have said that “Sri Lanka has a Scandinavian style welfare state with a Hong Kong style tax system” – it is difficult to disagree with this perception as the maintenance of these facilities has become a challenge given the ongoing economic crisis. In fact, the result has been an accumulation of public debt as government expenditure

has persistently exceeded revenue. It must also be noted that politicians respond to signals by voters. As Prof. Sirimal Abeyratne outlined in a recent article, “every time Sri Lanka has had a primary surplus in the budget, the incumbent government was voted out in the subsequent election”. Therefore, one cannot ignore a degree of collective responsibility for Sri Lanka’s fiscal malaise.

The culmination of Sri Lanka’s fiscal vulnerabilities was the deep and unprecedented economic crisis that reached a peak in 2022. The long-standing structural weaknesses were unravelled as ill-timed tax reductions in end 2019 led to a collapse of the country’s credit ratings. This was compounded by exogenous shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic and commodity price hikes associated with geopolitical tensions. In the absence of global financial market access and continued service of external debt, reserves declined rapidly and the inevitable sovereign debt default took place in April 2022.

I have over four years of direct experience on Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. The first two years, I spent at the Central Bank as a Deputy Governor. I very clearly saw the crisis approaching. I made every effort to apprise the then Governors, the then Monetary Board, and the then Ministers of Finance, on the impending serious crisis. Unfortunately, my early warnings, like many others’ at the time, were not heeded. Eventually, we as a country ended up in a disastrous crisis. Sri Lanka experienced a “great crash”. The government machinery was struggling to find solutions. Some of the key decision makers, both at a political level and administrative level, vacated their positions hastily. At times, during the worst of the crisis, it felt like there was virtually no functioning government.

As a consequence of the crisis, the entire 22 million population of Sri Lanka had to “Pay the Price”, a huge price, particularly for the poor and the vulnerable, from North to South and East to West, with no exceptions. The impact was, as we all know, extremely serious. The significant increase in multi-dimensional poverty, food insecurity, malnutrition, the collapse of the MSME sector etc. provide ample evidence of the destructive implications of the crisis. In fact, Sri Lanka’s experience clearly reflects the human cost of economic mismanagement in a country.

In the following two years, I was entrusted with the task of assisting the government in managing the crisis as the Secretary to the Treasury. As you may imagine, it was not a “business as usual” situation. It was in the midst of a deep crisis that had unimaginable challenges and implications. The Treasury was metaphorically burning. Anxiety, hopelessness and frustration was everywhere. There was a need for a cautious, focused and determined approach to handle the issues despite enormous negativities prevailed at the time. As Dr. Harsha de Silva, Member of Parliament, has opined in one of his tweets just after a meeting held with the Opposition Leader in early May 2022, where I also participated, the “Situation (is) grave. Going to be unenviable gigantic challenge for anyone to save Sri Lanka”. This was a clear reflection of the real status of the Sri Lankan economy at the time, which was indeed a desperate situation.

Over the last two years, a comprehensive and coordinated set of macroeconomic and other policy reforms were implemented to bring the country to where it is today. Many remedial measures, which would only provide benefits in the medium to long term, were introduced at the expense of measures that provide a short term boost, which has been the practice of the past.

Today, Sri Lanka is gradually emerging from the economic crisis. The macroeconomic reform programme has thus far been able to re-establish a degree of stability in the economy from the height of the economic crisis. As economic stability is being restored, it is essential that the stability is converted into inclusive and sustainable economic growth, such that the prosperity and well-being of all Sri Lankans is enhanced.

I am making these remarks based on the knowledge that I gained and the pain that I went through during the crisis management process, a unique experience that could be described as a once in a lifetime experience. In fact, the reform measures put in place over the last two years are with the hope and expectation that future policy makers and economic administrators would never make the same policy mistakes made in the run up to the economic crisis and would never face a similar experience in the coming decades.

Today, Sri Lanka is in the process of pulling itself out of the deepest and most complex economic crisis it has experienced in post-independence history. It is said that one should never waste a good crisis. If there is one positive that I could note from this crisis, it is the fact that the “Bar has been raised” with respect to expectations of responsible macro-fiscal management and improvement of governance in the country during the last two years. Many legislative and institutional frameworks have been introduced to address the structural weaknesses in economic management and governance that have plagued the country in the past.

Sri Lanka has had a long history of incomplete economic stabilisation programmes. The country’s macroeconomic framework has historically been characterised by persistent budget deficits and deficits in the current account of the balance of payments. This twin deficit leads to frequent balance of payments crises, reserve depletion, and bouts of inflation. As the crisis sets in, Sri Lanka has often sought the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), following which macroeconomic stabilisation measures are introduced. However, as soon as a degree of stabilisation sets in, Sri Lanka has a tendency to revert to past habits of fiscal excess, accommodated by monetary policy. Following several such cycles, in the lead up to the economic crisis, Sri Lanka ran out of all of its fiscal and external reserve buffers as the public debt to GDP ratio increased to around 120% and usable forex reserves declined to near zero levels in 2022. It is important to understand that it was Sri Lanka that went to the IMF in mid-March 2022 to obtain assistance when the economy was in its weakest footing, a decision which was delayed unnecessarily until then by the then senior economic administrators.

It is in this context that the economic reforms are being implemented. Preventive measures are being implemented proactively in many areas in contrast to the reactive curative measures introduced in the past. Ensuring macroeconomic and financial sector stability, while protecting the poor and most vulnerable, are the key priorities in the reform process. The reform program continues to be structured around seven main pillars: (i) an ambitious and primarily revenue-based fiscal consolidation, accompanied by institutional reforms and cost-recovery based energy pricing, aimed at restoring fiscal sustainability and strengthening fiscal discipline; (ii) a stronger social safety net to protect the poor and most vulnerable (iii) a sovereign debt restructuring process aimed at restoring public debt sustainability (iv) a multi-pronged strategy to restore price stability and rebuild international reserves under greater exchange rate flexibility (v) policies to safeguard financial stability (vi) focused reforms to address governance and corruption issues and (vii) broader structural reforms, including on trade and investment, to unlock Sri Lanka’s growth potential. These reforms have encompassed all key sectors of the economy;

Fiscal Reforms – Tax policy, tax administration,3 compliance and base broadening, expenditure management, fiscal legislature, including the landmark Public Financial Management (PFM) Act, to improve disciplined fiscal management and digitalization of Treasury operations through the Integrated Treasury Management Information System (ITMIS). These measures enabled Sri Lanka to convert a 5.7% of GDP primary budget deficit in 2021 to a 0.6% of GDP primary budget surplus in 2023.

State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) Reforms - Cost reflective pricing, balance sheet restructuring, institutional reforms, governance and legislation were introduced to reduce fiscal risks. As a result, the losses of Rs. 775 billion recorded in 2022 in key 52 state owned enterprises (SOEs) have been turned in to a profit of Rs. 456 billion in 2023, making a strong turnaround in their financial performance.

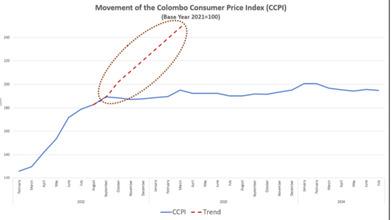

Monetary Reforms – The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act provides the legislative and institutional framework to enable inflation targeting. This contributed to inflation declining from 70% in September 2022 to 2.4% in July 2024.

Financial Sector Reforms – The amendments to the Banking Act and Banking Special Provisions Act were introduced while comprehensive reforms to the State Owned Banks (SOBs)4 are being implemented. Optimisation of capital deployment will be supported by new guidelines for business revival units in banks5 and the forthcoming Insolvency Bill. Strengthening SOBs and undertaking reforms will be done to reduce the sovereign- bank nexus through a Cabinet decision in April 2024, which overhauls the business models of Bank of Ceylon (BOC) and People’s Bank (PB) away from financing the budget and SOEs, and strengthen the governance framework for all SOBs; and (ii) a new regulation on large exposures, which addresses gaps that previously allowed excessive exposure to financially distressed SOEs.

Debt Restructuring – Sri Lanka concluded the domestic debt optimization (DDO) process successfully in 2023, enabling the debt targets to be met whilst ensuring financial sector stability. External official sector debt restructuring was also completed in June 2024. The final stages of the external commercial debt restructuring are now taking place. To provide the legislative and institutional framework to enable durable debt sustainability, the Public Debt Management (PDM) Act was passed by Parliament in June 2024 and the Public Debt Management Office (PDMO) will be fully established by end 2024.

Efforts to improve tax administration, including ensuring the seamless sharing of third-party data with IRD, the implementation of a VAT compliance improvement program, the approval of an Information Technology Strategic Plan to support the digitization of IRD (including upgrades to RAMIS) are also being implemented.

Growth Enhancing Reforms – To reduce trade and investment policy distortions and uncertainty, and restore the economy’s competitiveness and growth, the government has made significant efforts to modernize the country’s investment and trade frameworks. In July 2024, the Economic Transformation Act (ETA) was enacted, with the ambition of overhauling the existing institutional framework for trade and investment, boosting investment promotion efforts and attracting FDI, and building a foundation to promote economic competitiveness. In addition to the institutional framework, the new ETA also simplifies the investment entry process (including provisions to speed up approvals and implement other facilitation measures), increases transparency on restrictions, strengthens investor protection and sets the foundation for further business environment reforms.

Many of the above long neglected reforms have been discussed for around two decades and in some cases, for up to 50 years, as can be seen in the agreements signed by the Sri Lankan authorities with the IMF in 19777 and 19838. During this period, our neighbors, particularly in South East Asia, have adopted sound macroeconomic policies, integrated with the global economy and built competitiveness, invested in education, and attracted global capital and know-how, allowing rapid economic take-off and improvement of the quality of life of their populations. The following are a few examples.

“Statement of Economic and Financial Policies of the Government of Sri Lanka” attached to “Sri Lanka - Standby Arrangement”, 16 December 1977, International Monetary Fund. https://stoprdcom01e2.blob.core.windows.net/allfiles/IG/Production%20Hosting/Adlib/Public%20Documents/EB/236464.PDF 8 Sri Lanka - Letter of Intent”, 08 August 1983, International Monetary Fund. https://stoprdcom01e2.blob.core.windows.net/allfiles/IG/Production%20Hosting/Adlib/Public%20Documents/EB/103356.PDF

Let me remind you that the 7 percent primary surplus target is merely an intermediate goal. It is a means to an end. The substantive goal is the achievement of real economic independence, where Jamaica has the policy space to address its opportunities and challenges, without reliance on the multilateral community, in a manner that sustains and even enhances that independence”.

However, it is very unfortunate that Sri Lanka is still trying to implement some of the policies that were planned to be implemented 50 years ago, leaving the country well behind its peers in terms of economic development.

The inter-connected nature of the crisis makes navigating the required multi-dimensional reforms a difficult task. For instance, the interactions between fiscal policy measures, SOE restructuring, the state banks and financial sector, monetary and exchange rate policy, welfare policies, debt restructuring, result in a single policy measure having multiple impacts across other policy areas. Hence, deviating from the past experiences, a very carefully coordinated policy mix is essential to bring Sri Lanka out of this deep economic crisis on a sustainable manner.

Therefore, the present extremely narrow but unique window of opportunity should be used wisely to once and for all to implement deep and permanent structural reforms to address the fundamental flaws in the economy. This should be executed without being swayed by ideological dogma, but by following an evidence based professional approach, while avoiding any policy mistakes or experiments, which will be extremely costly and unaffordable to the country.

Whilst the reforms undertaken over the last two years have been largely successful in stabilizing the economy, there is also a public expectation in terms of a fundamental change in the quality of economic, political, and social structures in Sri Lanka.

The size of Sri Lanka’s economy should be enhanced substantially in the next decade by integrating into the global platform for knowledge based, sustainable and innovation focused businesses while emphasizing enhanced research and development in emerging sectors. A more transparent and accountable government should be fostered to restore the public trust in the government, which was seriously eroded in the run up to the crisis and during the crisis.

Deep-rooted governance issues and corruption vulnerabilities could contribute to economic challenges and social issues in a country. Corruption has also been identified as a macro critical component in the macroeconomic management and growth process. According to the IMF, “Corruption undermines growth and economic development, its economic and social costs are high, and transparency, effective institutions, and leadership are key factors of success. By vigorously reducing corruption, countries can improve economic stability and boost growth and development”.

IMF Survey: Fighting Corruption Critical for Growth and Macroeconomic Stability—IMF, 11 May 2016

In this regard, the government of Sri Lanka requested the IMF to conduct a Governance Diagnostic Review, the first in Asia, to identify potential gaps in governance and corruption vulnerabilities, with a view to implementing an evidence based process to address such gaps. Following the publication of this report in 202313, the government has published an Action Plan14 in February 2024 and is implementing key steps in the Plan. Steps to address corruption must be taken and they are being taken. The Anti-corruption Act was enacted in August 2023, which strengthens the asset and income declaration framework and investigative power of the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC). Following the Act’s approval, rules for the appointment of CIABOC Commissioners were gazetted in December 2023. Publication of asset declarations by senior officials15 in government commenced in July 2024. Key sections of the Anti-Corruption Act, such as sections 109 and 114 (5)16, give effect to asset forfeiture in relation to corruption related offences.

Whilst it is impossible to eliminate corruption and governance lapses overnight, it is essential to have a robust institutional and legal framework with appropriate checks and balances to make this goal a reality. Over the last two years, the first very significant steps towards addressing broader governance issues in the country have been taken.

Specific measures, led by the Ministry of Finance, have been taken to address issues of fiscal governance17. A “system improvement” is being implemented at the revenue collecting agencies. This is not only an effort to improve the systems but an effort to address deeply entrenched legacy issues in these institutions as well – addressing the longstanding weaknesses in RAMIS being just one example. The measures to improve governance and address corruption vulnerabilities in these institutions include the introduction of codes of conduct, establishment of Internal Affairs Units which have already yielded positive outcomes18, a High Wealth Individuals Unit (HWIU) at the IRD, strengthening of audit function to focus on risk based audits, and most importantly digitization are part of these efforts. A Criminal Investigation Unit (CIU) has already been established as a sub-unit within the Large Taxpayer Unit (LTU) at the IRD to identify and investigate cases related to crime proceeds. This will operate as a separate unit starting from January 2025.

“Where a court convicts a person, the court may, for any offence under this Act, make order that any movable or immovable property found to have been acquired by the commission of such offence or by the proceeds of such offence, be forfeited to the State free from all encumbrances”.

It is important to understand that even if one hundred percent of these governance gaps are eliminated, the gap in the budget deficit could not be filled. The government expenditure largely comprises very rigid non-discretionary items, such as public sector wages and pensions, interest cost, essential welfare payments. Just the interest cost, pensions and the salary bill alone easily surpasses government revenue. Therefore, even with zero corruption and perfect governance, tax revenue must still be enhanced and expenditure should be managed responsibly with strict discipline in order to reduce the budget deficit and borrowing requirements.

Some groups claim that “the tax burden on the people can be relieved once stolen assets are recovered”. I do not have the evidence to comment on such assets in Sri Lanka, but if we consider the experience of other countries, asset recovery takes an exceedingly long time.

Take the case of the Philippines, it took over 18 years for recovery of a small component of estimated ill-gotten gains since Ferdinand Marcos was ousted in 1986.

Unfortunately, in Sri Lanka’s case, time is not a luxury that we have. When the Treasury has to pay salaries at the end of this month, we do not have the option of telling our teachers, doctors, lecturers and civil servants to please wait for a couple of decades and they will be paid eventually. Nonetheless, even though asset recovery has limited near term fiscal benefit, it is crucial to have a framework to enable asset recovery from the perspective of justice.

One of the most important elements required for recovery of assets related to corruption is the legal framework. That is why the recent Anti-Corruption Act incorporates the key elements of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). At the same time, the proposed Proceeds of Crime Bill, which is in very advanced stages of drafting, will help address the issue of ill-gotten asset recovery in Sri Lanka.

“Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative: Challenges, Opportunities, and Action Plan”, p.21, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2007.

We often hear in the public debate of the need to invigorate the production economy in order to drive economic growth. Most often proponents of the production economy refer to a need for industrialisation, where economic growth is led by the manufacturing sector, which creates some product. Proponents argue that a production economy would lead to a higher degree of production than consumption, creating an exportable surplus. In this process, manufacturing and industrial sector jobs would be created along various value chains, leading to higher prosperity. Many proponents of the production economy either explicitly or implicitly suggest that industrial sector growth is somehow superior to economic growth led by the services sector. They assert that the government has a role to play in the propagation of a production economy by implementing a strong industrial policy, including investments in R&D, training, and various other interventions.

Whilst there are several merits to the concept of a production economy, a narrow focus on the industrial sector may not lead to the optimisation of economic and social returns for a country like Sri Lanka. There are several reasons for this;

None of this is to say that there are inherent problems with the manufacturing and industrial sector, but the point here is that an exclusive or predominant focus on this sector is not an optimal approach.

A more constructive approach would be to focus on competitiveness, more broadly. That is to focus on expansion of highly productive sectors, irrespective of whether they are in manufacturing, services, or agriculture. For example, a highly protected, globally uncompetitive shoe manufacturer selling to the domestic market is likely to be less productive than a highly competitive logistics service provider that competes with the top global logistical companies. A more productive entity will have higher real wages, generating better livelihoods and greater prosperity and well-being to citizens.

One of the keys to productivity is whether a sector is tradable or not. In the past, technological limitations meant that only goods were tradable, making industrial sectors typically more competitive than protected services sectors. However, with the advent of the digital economy, almost all services are now tradable as well, from professional services like architecture and engineering, to design and management consultancy. Sectors exposed to trade and competition are forced to be more productive, and higher productivity is what drives growth in real wages. Accordingly, if the objective of a government is to enhance the livelihoods and prosperity of the population, it should focus on growth of sectors that are tradable and highly competitive. The objective of government policy must then be to create an environment that enables such sectors to thrive by maintaining macroeconomic stability, removing impediments and facilitating the skills and other inputs required for those sectors.

There have been numerous recent statements by various groups regarding re-negotiation of the IMF supported reform programme. However, Sri Lanka’s present IMF supported Extended Fund Facility (EFF) programme is very different to Sri Lanka’s past programmes with the IMF given the fact that the restructuring of public debt is an integral component of this 17th programme.

The debt restructuring process envisaged in the programme is required to provide debt relief such that the key debt related targets as set out in Sri Lanka’s Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) can be met by 2032. The DSA is based on the IMF’s Market Access Countries Sovereign Risk and Debt Sustainability Framework (MAC SRDSF)21. The MAC SRDSF is a model applied to emerging market countries in general and is based on a combination of historic trends, peer country comparisons, and interactions between different variables (for instance the GDP growth projection would interact with the degree of fiscal consolidation, real interest path, and other variables).

Therefore, the outputs of the MAC SRDSF model are to a great extent mechanical in nature, with very little room for judgment and negotiation. Judgment based adjustments are also subject to inter-departmental review at the IMF and finally the decisions of the IMF management and Executive Board.

One of the key inputs for the DSA is the primary budget balance target. Sri Lanka’s programme includes a primary budget surplus of 2.3% of GDP from 2025 till 2032. This forms a key input into the Gross Financing Needs (GFN) target in particular.

The primary budget balance in turn determines the fiscal path in terms of how revenue must increase and expenditure must be managed to enable the 2.3% target to be met. The fiscal path in turn influences the interest rate trajectory, which influences the growth path. The macroeconomic baseline also includes an international reserves path, which influences the currency trajectory, which interacts with inflation. All of these contribute to determine the GDP growth path in the baseline.

It is a failure to understand the dynamics of these macroeconomic interactions that has led many to believe that the IMF targets can be casually re-negotiated and adjusted to meet various political or ideological ends. The bottom line is that expectations for re- negotiation of Sri Lanka’s DSA targets are based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the IMF programme structures, particularly one including debt restructuring. The targets are non-negotiable, whilst there can be some flexibility in terms of how those targets are to be achieved.

For example, earlier this week, the Hon. President announced some proposed amendments to the Personal Income Tax (PIT) structure. The Treasury began negotiating such an amendment with the IMF as far back as September 2023. It was not possible to implement such a proposal previously given the fact that revenue was falling short of targets. However, with the improvement in revenue performance this year, it has become possible to negotiate an adjustment to the PIT structure which provides some relief to the tax payers in the middle bands, whilst ensuring there isn’t an excessive gain for the highest income earners. The proposed adjustment to the PIT is estimated to cost around 0.08% of GDP and compensating revenue measures have already been discussed with the IMF, such that revenue targets are not compromised. As has been stated previously by the government, whilst the ultimate programme targets are largely non-negotiable, the policy mix by which such targets are met has more flexibility. In this instance, the ultimate targets of tax revenue and the primary balance are not compromised since the government has quantified the revenue impact and already discussed compensating revenue measures with the IMF.

Sri Lanka has gone to the IMF 16 times before this 17th programme, which began in 2022. In my view, this 17th programme should be the last one and we should use this as an opportunity to implement the critical reforms to put the country on a sustainable path. Let us recall Mr. Nigel Clarke’s rationale for Jamaica’s fiscal reforms, “The 7 percent primary surplus target is merely an intermediate goal. It is a means to an end. The substantive goal is the achievement of real economic independence”. So, it is abundantly clear that it was our failure in the past to “put our house in order” that led to Sri Lanka’s economic plight. Now, at least after this serious economic crisis, our duty and aim should be to implement required reforms following a focussed and committed approach to strengthen our economic levers and buffers so that, “we Sri Lankans can achieve our real economic independence and even enhance our economic independence”, going forward.

The crisis had disproportionate impacts on the poor and vulnerable, exacerbating existing social inequalities. The remedial measures to address the crisis at times added to the shocks faced by these groups. In fact, some critics argue that even though the economy has stabilized, this has happened at an adverse equilibrium where costs are higher and incomes have not caught up.

Whilst accepting that it is true that costs are higher and incomes have not yet caught up, it is also important to consider the counter-factual. What would have been the outcome if the reforms had not been implemented two years ago?

Source: Department of Census and Statistics

The coordinated monetary and fiscal policy measures were able to control inflation from the latter part of 2022. If this had not been done, inflation could have continued to increase like it has done in other countries that have undergone sovereign debt crises.

|

|

Inflation |

Date |

|

Ghana |

23.1% |

May-24 |

|

Zambia |

15.2% |

Jun-24 |

|

Argentina |

276.4% |

May-24 |

|

Lebanon |

51.6% |

May-24 |

|

Venezuela |

59% |

May-24 |

|

Suriname |

20.7% |

Apr-24 |

|

Ethiopia |

23% |

May-24 |

|

Ecuador* |

2.5% |

May-24 |

|

Sri Lanka |

2.4% |

Jul-24 |

*Ecuador is a dollarized economy

Once inflation is brought under control, as it was done successfully in Sri Lanka, nominal wages will gradually rise to compensate for the loss in real earnings due to inflation. However, typically this period of wage catch up does not occur immediately, but happens gradually as the economy recovers and productivity driven economic growth returns. Between January 2022 and May 2024, private sector wages have increased by 32% in nominal terms according to CBSL’s wage rate indices22. During the same period, public sector wages have increased by 21% in nominal terms. This trend will continue as long as economic stability is intact, allowing growth enhancing measures to take full effect.

The protection of marginal groups, who face the brunt of the crisis and could be potentially excluded from the broader economic process, is crucial. The empowerment of women and the elderly are the other key areas that are being addressed given the importance of empowering them. The reduction of multi-dimensional poverty is also a priority by improving social safety nets, education and health facilities, and creating economic opportunities towards promoting more inclusive and sustainable growth.

Social protection reform became one of the priority reform agendas of the government as it attempted to address the crisis. The Samurdhi framework was overhauled with new selection criteria being implemented. The new criteria were based on objective, verifiable factors which minimized room for subjective decisions or politicization. A clear framework for application, verification, and transparent selection was implemented. Another key mechanism was the grievance handling process and allowing for appeals and review. Naturally, like with any other major reform after three decades, there have been teething issues and resistance. However, with the grievance handling mechanism falling into place, these issues have eased. The new mechanism has been named Aswesuma.

The cash transfers now take place direct to the beneficiaries’ bank accounts, and the improved selection mechanism has enabled a larger allocation of funds to each vulnerable household. The total cash transfers to vulnerable households have increased by over three-fold compared to pre-crisis levels in 2019. In 2020, the budget expenditure for school nutrition food programme was Rs. 2.3 billion which increased to Rs. 12.5 billion by 2023, with the number of beneficiaries more than doubling during this period. Public expenditure to fund school text books increased from Rs. 4.8 billion in 2018 to Rs. 23 billion in 2023. Government expenditure on free medicines for the general public increased from Rs. 54 billion in 2019 to Rs. 144 billion in 2023.

The total cash transfer each year is also a quantitative target under the IMF supported EFF programme, with a floor under the minimum transfers each year. A graduation mechanism is also being put in place, whereby those who are no longer eligible for cash transfers will still receive other non-cash benefits, such as livelihood support, concessionary financing, among others.

However, cash transfers are just one element of the broader policy ambit of social protection. As mentioned at the beginning of this address, Sri Lanka has had a long history of social welfare policies, however there is a long way to go in terms of optimizing such measures for the full benefits to accrue to the population. One of the key shortcomings in Sri Lanka’s social protection architecture is the lack of a holistic Social Protection Policy. The shortcomings resulting from this are many, including issues ranging from coverage of beneficiaries to adequacy of benefits. Furthermore, fragmented programmes, schemes, institutions, and products which are integral to the current social protection system have been proven to be inadequate, resulting in sub-optimal developmental outcomes.

To address this gap, the government developed the National Social Protection Policy. The key pillars of the new social protection system include social assistance, social care, social insurance, and labour market and productive inclusion programmes. The policy is underpinned by the principles of equity, inclusivity, and sustainability, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently and effectively, to reduce poverty and social exclusion, fostering a society where everyone has the opportunity to thrive. The principle of ensuring access to necessary social protection for all citizens throughout the lifecycle is embodied in this policy.

Today, Sri Lanka has come to a decisive moment in its journey to crisis resolution and prosperity. In “Shaping the future: Policies for dynamic growth towards improving social protection and the Well-Being of the people“, a carefully thought out, evidence based approach is essential. Although there are signs of positive economic activity emerging and reform efforts have started to bear fruit, it is critical to remain vigilant and fully committed to the reform agenda envisioned at the onset of the crisis. This is critical to ensure a sustainable economic recovery that is embodied by human wellbeing, ecological sustainability and social justice.

The path ahead is not easy and will be full of obstacles. The country and the people should be vigilant of the developments and risks, both domestically and internationally. If we continue to implement rational, evidence-based policies, we as a country can strengthen resilience of the economy by rebuilding macroeconomic buffers, thereby setting the foundation to prosper in the coming years. If we ignore early warnings, and make drastic and irrational deviations from the policy framework, there will be serious negative consequences for the economy.

Going forward, the country needs a “Social Contract” for a long term vision that will be implemented with specific attention to periodic revisions required to suit emerging situations. It is important to have this type of a vision as the country has been battered due to short sighted, opportunistic and politically motivated policies implemented in the past.

In the meantime, there are voices raised for a systems change. A system change can be defined as “’shifting component parts of a system — and the pattern of interactions between these parts — to ultimately form a new system that behaves in a qualitatively different way’.

….We navigate interdependent webs of systems every day, all of which have complex interconnections and unique relationships. For example, a family, a community, a nation. Likewise, our transport system, food system and cities. Thinking systemically generally involves seeing the whole rather than just parts, seeing patterns of change rather than static snapshots, understanding key interconnections within a system and between systems, engaging different perspectives, constantly learning and adapting and probing assumptions.

….Changes in one system can cause unforeseen consequences in others. If we are to create a sustainable and just future for all, we must navigate these with a systems lens to fully grasp the complex dynamics….

….(For example) the latest science tells us that we must limit warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) to prevent increasingly dangerous and irreversible climate change impacts. It also tells us that we must protect, sustainably manage and restore ecosystems, among other actions, to halt biodiversity loss as soon as possible. To achieve all this, we need fundamental change across nearly all major systems by 2030 — power, buildings, industry, transport, forests and land, and food and agriculture. Cross-cutting transformations of political, social, and economic systems must also occur to enable this and ensure the change is socially inclusive with equitable outcomes for all”

The above quotations highlight the importance of having changes in all the related systems with cross-cutting transformations to achieve desired objectives and “ensure the change is socially inclusive with equitable outcomes for all”. Unfortunately, it is observed that there is a resistance to change in many areas in the society both among individuals and institutions. If someone is serious of a system change, it should begin from the individuals themselves, before asking others to change. The true change begins with an individual’s own conscious. The “Lord Buddha always emphasized on changing the self-first to bring about a change in the world. He said: “Only a man himself can be master of himself: who else outside could be his master?”25. This should be applied to all individuals, regardless of their social strata or official positions.

There is a long and difficult journey ahead of us towards achieving higher economic growth, creating quality employment, and enhancing well-being of the people. In the past, we have attempted many short cuts, but these are no longer options. Considering the period between April 2022 and August 2024, an objective assessment of the evidence so far indicates that the reforms being implemented are working. This is not to say that the reforms are not associated with pain and economic stress for the citizenry. The people have gone through a tremendous pain and stress and it was because of their patience and tolerance that helped the country to stabilise within a relatively short period of time. However, the alternative to reform, the counter-factual referred to earlier, would have been a far worse outcome.

There have been various theories as to what caused the economic crisis, including the COVID-19 pandemic, ISB borrowings, the Debt Standstill policy. However, it is clear that the fundamental cause has been long standing macroeconomic vulnerabilities and domestic policy errors. There have also been various alternative proposals and theories as to how the country can recover without the citizens having to bear a burden. But, it is important to understand that measures such as asset recovery, collection of taxes in arrears, elimination of corruption, while all being essential actions, do not serve as an alternative to the macroeconomic reforms being implemented today. These are reforms that were known to all of us for years if not decades. But, these much needed reforms were delayed mainly due to a lack of political will. As I have indicated previously as well, in the past, and up to now, the present generation lived a better life by borrowings thereby sacrificing the lives of the future generations. However, it is critical to understand that now we have come to a situation where the present generation should make sacrifices for the betterment of the lives of the future generations.

Based on developments and the judgment based on my experience in dealing with the economic crisis, I see that the country is at another crossroad today, possibly the most critical cross-road yet. Over the last two years, the country has undergone necessary but painful macroeconomic reforms with the support and sacrifices of the people and assistance from the international community. Sri Lanka is gradually emerging from the crisis and eventually the country will be poised to rise strongly by exploiting its huge.

untapped potential. However, there are risks associated with any abrupt deviation from this knife-edged reform oriented growth path. So, we should all be very cautious and careful in navigating the very delicate situation in the Sri Lankan economy at present. In my view, the achievement of dynamic growth, which will ensure the social protection and well-being of the people in the generations to come, will depend on the measures to solidify the stability and the way we respond to the extremely challenging situation today. This is my message for all Sri Lankans to consider.

Leave Comments