By Deshai Botheju, Ph.D.

|

“The term 'natural disasters' has become an increasingly anachronistic misnomer. In reality, it is human behavior that transforms natural hazards into what should be called unnatural disasters”

|

The global pandemic of COVID-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus is instigating a mass disruption of the normal societal functioning and costing billions of worth of economic harm across the continents. This is a large scale biological hazard, that we need to go back almost 100 years in history to find anything matching the level of havoc it is causing now. The nearest historical example is 1918 Spanish flue influenza caused by the avian origin virus H1N1 which is estimated to have caused a death toll of more than 17 million across the globe.

A widespread biohazard is one of the many types of large scale catastrophic events that can trigger a global scale societal breakdown.Responding to large scale catastrophic events is always challenging. Managing such events involves a complex mix of socio-economical and technological dimensions. Understanding various human limitations and behavioral characteristics early in the process can often give an advantageous head start. This article presents several Human Factors associated aspects that should be given attention when managing large scale societal safety emergencies such as COVID-19 outbreak.

Human factors in emergency management

Within the societal safety domain, emergency management (or disaster management) can be defined as the managerial process addressing the aspects of i) Preparedness ii) Prevention, iii) Response, and iv) Recovery against large scale disasters. Based on the above four (4) key objectives, it is indicated here as 2P2R approach.

Human factors should be important considerations in societal safety and emergency management. The same concepts are broadly applied in industrial safety management and associated emergency preparedness activities. During last few decades, industrial safety management field gained noteworthy advantages by applying human factors as a part of engineering and designing the products, systems, and procedures in order to prevent large scale industrial accidents as well as for enhancing occupational safety. The wider application of the same concepts in societal safety management willobviously produce substantial rewards.

Human factors can be introduced as an aggregate of knowledge on human behaviors, human capabilities, human limitations, and human errors with respect to the safe and efficient management of a certain system. The concerned system could be a technological system such as a large production plant, or it could very well be a procedural system aimed at achieving a particular target, such as preventing or responding to a large scale disaster.

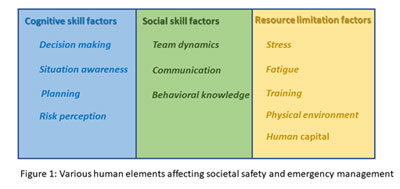

Inclusion of human factor aspects in emergency management can significantly increase the eventual success rate of the exercises. Lack of such insight often lead to poor management inputs and failures in achieving desired outcomes. The higher the needs of human involvements in large scale disaster response activities such as COVID-19 mitigation, the more important is the use of human factors knowledge in managing such processes. Let us discuss some of the applicable human factor concerns regarding the current pandemic situation, with primary attention placed on the Sri Lankan context. Figure 1 presents a summarized view on several associated factors separated into three (3) categories; including 2 skill categories (cognitive and social skills) and one resource category.

Patient behavior

Understanding human behavior should be a big focus when responding to disasters. Within the context of COVID-19, one key error that must not happen is to victimize the patients. Threats, media abuse, and subjugation will all lead to the patients being forced to go underground. Such practices found in historical contexts all teach us one lesson. That is, for mitigating pandemic spread of diseases, the society has to be open and welcoming to the patients where they can freely seek medical care without the fears of reprimand, refusal, and punishments. Forceful actions will always be met with counterproductive responses from the society that will eventually lead to failure in containing the disease. Based on a human factor perspective, it is important to understand that behaviors such as being afraid, not seeking medical attention, or being reluctant to quarantine are all natural human behaviors under stress, or when traumatized by the negative societal response. Emergency management must address this aspect and create an environment where patients can become visible freely and voluntarily. In a global context, this is the exact approach used in Scandinavian region countries (where the author is currently residing) at this juncture,and they are well on their course to successfully countering the outbreak.

Team dynamics

Human factors play a major role in team dynamics during crisis management activities. Managing large disasters needsextended teams working at various levels. Many of these teams are comprised of individuals with diverse backgrounds and expertise. Not necessarily all of them speak the same language even though they use the same language. This means, not everybody understands each other due to various technical specialties and also due to different professional cultures within different professional groups. Often, these teams are put together in an ad-hoc manner due to the urgency of the situation. The familiarity and the trust within team members can be minimum or non-existent. Under such situation, certain team members may not feel enough “psychological safety” to open up and be communicative. In contrast, some team members can be dominant over others.

The cooperation and coordination within such teams can be extremely challenging and chaotic. This is a particular area where the emergency management leadershipshould pay attention. The leadership skill itself is a vital human factor concern in emergency management. Sometimes, it is best to use a few generalists who are skillful in human management to enhance the team dynamics and improve interplay and assist translating each other. Such resource personal must be able to ensure the psychological safety of the group members and adequately moderate overacting members. This situation found in societal disaster management is quite different from industrial safety management. In safety critical industries, crisis management teams are often pre-defined well in advance. They also undergo regular training sessions, sometimes including simulated crisis situations. Such teams know each other, understand each other, and also expects what emergencies to happen. This is one area that societal safety management field can learn from industrial safety management professionals. Predefined crisis management teams based on different disaster scenarios recognized during national level risk assessments can help rapid deployment of them in an actual emergency situation, and also will lead to formulate better teams that can work coherently and efficiently.

Communication and risk perception

Communication is another major area needing human factor based aproach during emergency management. We have briefly discussed potential inter (or intra) team communication difficulties in the previous section. Here we put more attention to the public communication aspects during emergencies. It is crucial to have a transparent and open communication strategy from the early phases of crisis management. If the management team is exposed to have delivered incorrect or misleading information, thereafter the public trust on the whole emergency management process will becomelower. Such broken trust is hard to regain. The concept of risk perception comes into the picture here. The risk perception is the “risk feeling” that public receives via various communication channels or via their own observations (or experiences). This risk feeling can be very different from the actual or statistical risk that the subject experts have estimated. For example, due to the information they are receiving, public could overestimate the danger of a biohazard such as COVID-19. Similarly, in another society, the public might underestimate the same risk. Both types of risk perceptions are not good. While the underestimation could lead to weaker compliance to safety precautions, the overestimation is equally bad. Overestimation can easily lead to panic, societal chaos, subjugation and discrimination, violence against patients or suspected persons, total shutdown of the economy, and such great harm. Therefore, it is extremely important to deliver correct risk perception to the society with the correct dose of emphasis. Formulation of public information, warning messages and their structure, clarity of the guidance with attention to any contradictions, as well as the personnel entrusted to present such information must be chosen with great care. It is recommended to seek opinion from multi-discipline teams in such matters, without resorting to a single group of professionals who could often have certain tunnel vision towards the disaster in progress.

Decisions under stress

Making right decisions during a crisis situation involves the most challenging aspects among all management activities. The decisions have to be made in a time-critical environment with rapidly changing dynamics. The available information is not often complete, and can be inaccurate. Or in some occasions, information overload can also happen. Further, decisions can involve a tremendous societal pressure. In the current era, social media also create a large impact on the decision makers. Making decisions under stress and overloaded conditions can lead to miscalculations and human error. The continuous retention of the situational awareness can become difficult. Biases in thinking processes, and certain stereotypes can also impact decisions. These are well-recognized issues in industrial safety management. Lot of human factor studies have been conducted with respect to industrial settings. It is very useful to adopt such learninginto the societal emergency management arena where human factor focus is still minimal in many parts of the world.

Imperfect conditions

Another challenge faced by emergency responders during a large societal catastrophe is to work under imperfect conditions. They may not have access to usual infrastructure or resources that are available under normal situations (e.g. power supply, communication, transport, etc.). The crisis teams, as mentioned earlier, may have hurriedly chosen in an ad-hoc manner. Many of the team members might not have enough or proper training to carry out the tasks that they are supposed to carry out. Fatigue and over-stretched resourcesoften lead to poorer human performance. Such conditions exert a great deal of burden on human capabilities, and often exceed human limitations. In industrial safety management, all these aspects are considered well in advance and are analyzed in detail to formulate solutions. Many human factor studies such as situation analyses, workload analyses, analysis of human error potential, etc. are conducted already in design stages of the industrial facilities. Societal safety and emergency management field is encouraged to adoptsimilar methodologies, with relevant modifications.

Human capital

When facing a global scale catastrophic event such as COVID-19 outbreak, it is a prodigious advantage to possess a well developed human capital. The societies with such populations are easily directed in correct course of actions. Looking at the Scandinavian countries and the way they are handling this crisis, we can clearly see that significant gains have been obtained with minimum government enforcements and without totally shutting down the normal functioning of the society and the economy. Freedom of movement, democratic rights, openness, and the normal life have been impacted to a lesser extent. On the contrary, some countries had to go to extreme extents to have an upper hand on the situation. For example, we could see in the neighbor country that police had to beat and chase down persons along the streets to enforce curfew. Therefore, in the long run, one of the best courses of action to face societal emergencies successfully is to develop its social capital.

Planning and preparedness

In several places in this article, we have pointed out that many of the human factor related challenges faced in societal emergency management are well addressed aspects in industrial safety management relating to safety critical industries (such as nuclear, chemical process, aviation, etc.). This is primarily due to the established regulations and standards guiding the industries to carry out detail risk assessments and to prepare comprehensive emergency preparedness plans. Further, such safety critical industries often have well-developed safety cultures dominating the behavioral safety. Indeed the same concepts should ideally be applied for societal safety management as well. A country level risk assessment must be conducted to identify and analyze various hazards and risks that the country may expect during a predefined time interval (say next 20 years). Based on such national level risk assessments, emergency preparedness plans must be formulated against various large scale disasters that can be expected. Such plans should include necessary resources, resource personnel and teams, and detailed methods and procedures to be applied in preventing, preparing, responding, and recovering from such disasters (2R2P approach). In addition, appropriate risk acceptance criteria must be defined. The acceptable risk in terms of human lives, property damages, and economic harm should be quantified. Further, learning from previous disasters and the incidents happening in other parts of the world should be promptly extracted. Such learning can provide huge advantages either in preventing disasters altogether or having a significant time advantage if they should still occur. Such learning must also be properly documented as experience transfer reports and should also use them for standardization of certain emergency management protocols and procedures. This facilitates critical decision making under emergency situations and reduces the risk of human errors.

Final remarks

In 1999, then UN SecretaryGeneral Kofi Annan said, “The term 'natural disasters' has become an increasingly anachronistic misnomer. In reality, it is human behavior that transforms natural hazards into what should be called unnatural disasters”. A good 20+ years later, Kofi Annan’s words are even more valid for COVID-19 outbreak. Even though its origin might just be natural, this pandemic is causing unnatural harm in a truly global scale, mostly due to human behavior. Proper management of this disaster requiresunderstanding the associated human factor dimension. Societal safety and emergency management can extract a great deal of learning from industrial safety management in order to prevent, prepare, respond, and recover from such “unnatural disasters”.

|

Author Description Deshai Botheju [Ph.D. (NTNU), M.Sc.Tech. (USN Norway), M.Sc. &B.Sc.Eng.(1st cl. Hons) (UoM), AIChE, AMIE(SL)] The author is currently consulting for the Norwegian petroleum industry, within his field of expertise of Safety and Sustainability Engineering & Management. The key areas of his industrial experience and research interests include; Process safety & Industrial risk management, environmental sustainability &waste management solutions, and safety culture. By Deshai Botheju, Ph.D. deshaibotheju@acses.org

|

Leave Comments