By Jayantha Obeysekera

Floods are back again disrupting lives and damaging property in large parts of Sri Lanka. Also, in June of this year, intense storms and floods occurred seemingly with a vengeance.

This article is a follow-up to one that the writer wrote after the floods of May of 2017, about seven years ago. In 2017, the southwest monsoon hit Sri Lanka with a full force resulting in severe flooding and landslides across multiple southwest provinces affecting Nilwala Ganga, Kalu Ganga, Gin Ganga, and Kelani River Basins. That disaster led to over 220 deaths, and over 13,000 homes were fully or partially damaged. This year the scale disaster was not very different. Flood disasters seem to happen at an increasing frequency with increasing intensity disruptive lives.

According to recent reports, over 30 fatalities have occurred by June this year, a figure less than what was reported in 2017. However, any loss of life is unacceptable. The Disaster Management Centre (DMC) highlights that Colombo and Ratnapura districts were the most affected, with over 30,000 families displaced. More than 5,500 houses suffered damage, including 56 that were completely destroyed. Approximately 7,600 individuals were housed in 116 safety centers, receiving essential services and increased daily food provisions.

Additionally, the Ministry of Agriculture reports that the floods ravaged over 15,000 acres of paddy fields, although damage to upcountry vegetable cultivations has been minimal. However, as usually happens, both the public and the government appear to have already forgotten the disaster.

As the writer had pointed out in 2017, it is crucial to assess the flooding and landslides, and to formulate strategies that can mitigate similar impacts in the future. This sounds more like a broken record. Regrettably, our responses to past catastrophic floods have shown a pattern of failing to learn and plan effectively for future events.

Unfortunately, any follow-up actions from past flooding events have not led to substantial changes on the ground either in terms of policies or solutions. Once again, the flood disaster this year presents another opportunity to learn, develop, and implement plans that will mitigate the impacts of future extreme storms and floods. Ensuring protection against catastrophic flooding is as crucial to water security as ensuring food security is to the overall well-being of the nation. This falls squarely on the shoulders of those in power. Evidence shows that climate change is likely to make future flooding worse.

Implications of Climate Change

United Nations IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) projects that global warming will significantly intensify extreme rainfall events, making them more frequent and severe. This increase in heavy precipitation is expected to affect most regions around the world, although the degree of impact will vary depending on local geography and climate. Observational records show that May 2024 was the hottest compared to all previous years. The year 2023 was the hottest compared previous years.

Historical observations show that warming has not spared Sri Lanka where rising temperature has been observed in most locations. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, a well-known fact based on science. The evidence suggests that, with each 1°C rise in global temperature, extreme precipitation is projected to increase approximately by about 7% because of this greater moisture holding capacity due to warming. With intensification of storm dynamics, the rate of increase may even be higher. Specific impacts include more intense rainfall from tropical cyclones and enhanced monsoon precipitation.

To make things worse, sea levels are rising and they will rise faster in the future due to melting of land-based ice. The implications of sea level rise to island nations like Sri Lanka can be significant. Salt water will intrude into rivers affecting freshwater supplies and via groundwater salinizing coastal wells. Intensification of storms and rising seas will make the management of extreme floods like the one that occurred in early June much harder. These changes necessitate robust flood risk management and adaptation strategies to mitigate the anticipated effects in the future.

Managing flood disasters and landslides is inherently complex. Despite numerous lessons learned from each disaster, public complaints about immediate responses and the lack of preparation and planning are common. Immediate disaster response is a critical issue and that is normally not the problem. This article will instead focus on identifying potential inefficiencies in long-term flood management, which should help planning discussions regarding flood projection at all levels of the government and society.

Floodplain Management

Many of Sri Lanka's major rivers, including the Mahaweli, Kelani, and Kalu, originate in the central hills and carry substantial amounts of water to the ocean. These rivers have extensive drainage basins with numerous tributaries and smaller streams, referred to as Oya or Ela in Sinhalese, that flow into the main rivers. Adjacent to this intricate network are paddy fields and wetlands, which play a crucial role in storing floodwaters and slowing down their rapid movement downstream. Unfortunately, many urban centers, from villages to major cities, are situated along these networks and experience periodic flooding, as seen in recent events.

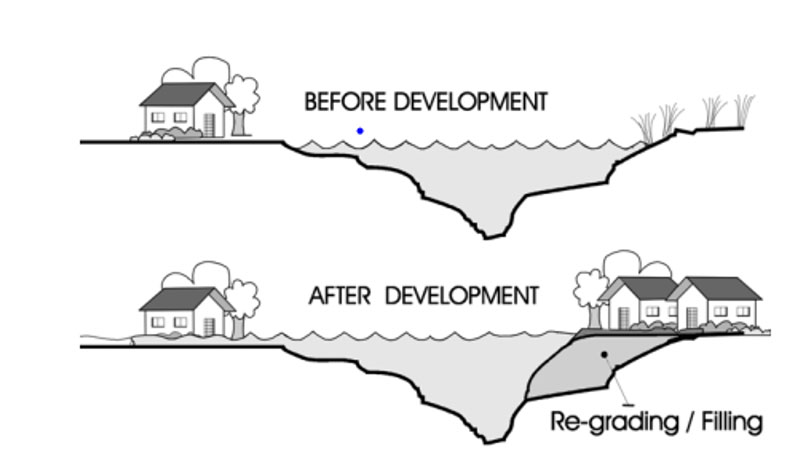

Flooding in river basins is a natural occurrence following heavy storms. However, human activities have significantly altered the landscape, exacerbated flooding leading to risk of catastrophic landslides. Key attributions for this include, but are not limited to:

Other modifications to the river basins may also contribute to frequent flooding. Flood maps from the May 2017 event revealed that many low-lying areas upstream of major rivers experienced flooding, indicating a lack of capacity to store or channel excess rainfall effectively. There are no designated floodplains, no standards for setting house pad elevations, and roadways are not designed to prevent disruptions during floods. This has led to unplanned encroachments into the floodplains.

Once again, there is an urgent need to evaluate the conditions within river basins that contributed to the recent flooding and to implement measures that can reduce future impacts.

Floodplain management is essential. According to FEMA in the United States, it involves making decisions to ensure the wise use of floodplains, which means reducing flood losses and protecting the natural resources and functions of floodplains. In Sri Lanka, there is a lack of effective floodplain management and no clear authority to address the numerous issues associated with the floodplains of major river basins.

The public needs to understand that it is neither feasible nor economical to protect against every major flood. For planning and informing the public, a "Special Flood Hazard Area" can be defined based on a "base flood" of a certain magnitude. In the United States, this base flood has a 1% chance of occurring in any given year, known as the 100-year flood. However, this term is often misunderstood; it actually refers to a flood with an average occurrence interval of 100 years, not a flood that happens exactly every 100 years.

A better way to is to recognize that the 100-year base flood has a 1% chance of exceedance in any year. During the May 2017 event, there was similar confusion, with some claiming it a 200-year storm. This is a storm with a 0.5% chance of occurring annually, not an event happening every 200 years. It is important to note that the 100-year flood (1% chance event) will likely be a more frequent event due to climate change in the future. As a consequence, the society may have to plan for a higher level of protection from flooding because of implications of climate change.

If a 1% chance flood is chosen as the regulatory base flood, the floodplain would be the area adjacent to a river or stream inundated by such a flood. Engineers can delineate this floodplain through detailed analysis, provided the necessary data is available.

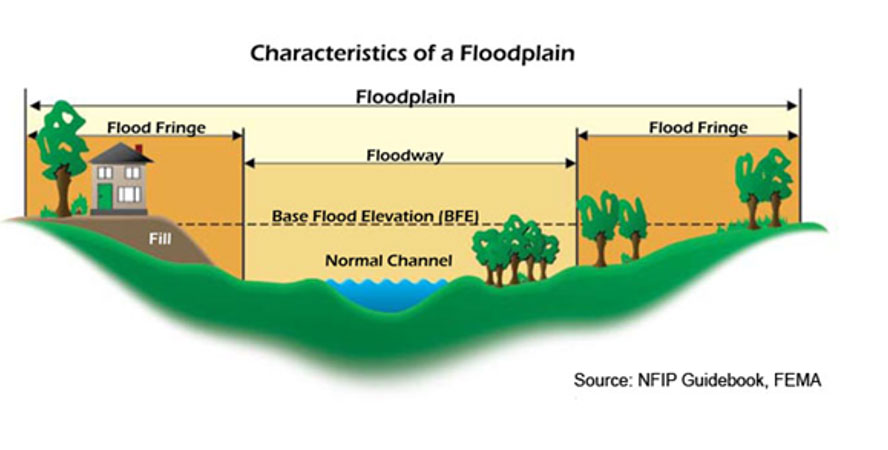

A floodplain can be divided into zones, typically the floodway and the flood fringe:

The base flood elevation determined by engineers can regulate building construction or encroachments within the floodplain. Properties within this area should be required to purchase flood insurance to mitigate damage from future floods.

Following the May 2017 floods, reports suggest the government is moving towards better floodplain management through a new Flood Management Act, which aims to replace the 1924 Flood Protection Ordinance. Judging from public discussions, the status of this Act is not clear. This new act could establish flood areas, forecasting systems, flood maps, infrastructure improvements, and coordinated flood management efforts.

If adequately funded and implemented, this act would be a significant step forward. Interestingly, the 1924 ordinance included provisions for repayment by landowners for flood protection costs, akin to modern flood insurance. However, there is little evidence that these provisions were ever enforced.

Figure 1: Definitions of floodplain, floodway, and flood fringe across a river section

Figure 2: Increased flooding due to floodplain encroachment

This act, if enacted and enforced effectively, could serve as a critical framework for managing flood risks and enhancing resilience against future flooding events.

Governance Issues

The central government of Sri Lanka consists of numerous ministries and a wide array of line agencies dedicated to various disciplines. In the realm of water resources management, these agencies are scattered across different ministries, complicating coordination, especially during disasters like the recent floods. Flood protection and landslide planning involve several key agencies, including the Irrigation Department, the Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation (SLLRDC), the National Building Research Organization (NBRO), the Department of Meteorology, and the Survey Department. Each of these operates under different ministries. The Disaster Management Centre, which has its own ministry, relies on information from these various agencies, leading to coordination challenges. Such a decentralized responsibilities may not be ideal for effective floodplain management.

Additionally, recent efforts by provincial councils to establish their own "Irrigation Departments" represent a positive move towards decentralizing technical activities. Ironically, none of these agencies explicitly include "flood" in their names, as their primary mandates focus on water supply and land reclamation. The decentralization of flood management across numerous ministries has led to inefficiencies, coordination problems, and jurisdictional conflicts. A potential solution, adopted by many countries, involves consolidating related line agencies under a single cabinet minister, streamlining coordination and oversight.

Another viable approach is the creation of a specialized central government entity dedicated to floodplain management, staffed by qualified professionals from various agencies. This entity should be empowered with clear mandates, training, and free from political interference. It would coordinate flood planning and management with professionals from other government agencies and provincial councils, providing essential data, technical assistance, and capacity building. An example of effective coordination can be seen in the administration of the Mahaweli River Basin, managed by its own ministry and agencies. This model could be extended to other large river basins, incorporating broader floodplain management responsibilities.

Clearly, there are multiple strategies to enhance coordination efficiency, achievable with genuine political will. Addressing this coordination issue is crucial.

Funding for flood management projects is another significant governance challenge. Many key projects, such as those in the lower basin of the Kelani River, depend heavily on international donors like the World Bank. Without sufficient funding, line agencies struggle to acquire necessary technology, data, and capacity for effective floodplain management.

The nation must recognize that economic development via major infrastructure projects must also prioritize the sustainability of our environment through sound governance and adequate funding. Structural solutions, such as building dams and reservoirs, should not proceed without first understanding the broader problem and considering necessary non-structural solutions through effective floodplain management.

Data and Technology

Effective flood management relies heavily on comprehensive and accurate data. This includes high-resolution topographic maps, land use patterns, soil types, rainfall data, water levels, and flood discharge magnitudes for rivers and streams. While government agencies have made progress in acquiring such data for project planning, there remains a significant shortfall in funding for ongoing data acquisition. The prevailing belief is that without international donor assistance, adequate funding cannot be secured. It is crucial for policymakers to prioritize the sustainability of water resources and ensure that government agencies receive sufficient funding for consistent monitoring and planning. The saying, "Take care of the land and the land will take care of its people," underscores the importance of maintaining natural resources through proper planning and science, even amidst large-scale infrastructure development. Ignoring these aspects will lead to unsustainable future outcomes.

A critical issue identified by the writer is the lack of data-sharing practices prevalent in many developing countries, including Sri Lanka. Essential data such as topography, rainfall, flood flows, soils, and land use are not readily available to the public and are often only accessible at high costs. This practice impedes progress for researchers and students who are qualified to analyze these data and contribute to understanding and predicting floods. Moreover, this lack of accessible data hampers the quality of computer modeling studies. Consequently, many choose to forgo proper investigations due to the prohibitive cost of data acquisition, leaving valuable data underutilized in agency archives. The long-term cost of not utilizing this data far exceeds the short-term revenue gained from its sale. Budget allocations should provide sufficient funds for data collection and dissemination, and agencies should be directed to make data freely available, especially for research purposes.

Recent developments, such as the Right to Information Act, should have included provisions for public access to geophysical data collected by government agencies, provided it does not compromise national security. In many developed countries, data is freely available online due to legal mandates, such as the Public Records Law in Florida, USA, which ensures that all state, county, and municipal records are open for personal inspection and copying by any individual. Progress requires overcoming current data policies to facilitate free use of data by those willing to utilize it.

Keeping pace with technological advancements, such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), is also essential for effective floodplain management. Reports indicating government interest in upgrading the Meteorology Department with high-resolution Doppler weather radar are promising. Radar data is crucial for obtaining spatial information on storm events, like the one in May 2017, especially given the inadequacy of Sri Lanka's rain gauge network. Enhancing real-time rainfall measurement and water level monitoring along rivers through telemetry or cellular networks is another area needing improvement. A centralized authority should establish a flood forecasting system using real-time data and well-established computer models for simulating floods in river basins.

Another persistent challenge is the lack of capacity building among engineers and professionals conducting flood studies. The writer’s experience in teaching flood modeling to SLLRDC staff and more recent capacity-building efforts for over 40 engineers through the Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science (SLAAS) highlight the potential for rapid progress with proper guidance and training. Recognizing the importance of developing local expertise at all governmental levels is crucial. Engineers produced by local universities are highly talented and, with appropriate training, can make significant strides in flood studies. Capacity building should not depend solely on donor agencies but should be supported through agency budgets.

In summary, the recent flood event should serve as a catalyst for focusing on floodplain management and revisiting governance and policies that have previously hindered effective flood management. While solutions from Western countries may not be directly applicable to Sri Lanka, valuable lessons can still be learned. Relying solely on donor funding for planning will result in reports gathering dust on shelves. Political leadership must recognize the talent of local engineers, provide adequate funding, and heed their homegrown solutions for managing floods efficiently. This proactive approach can prevent the recurrence of the “monkeys building houses” scenario, where plans are only discussed during disasters and abandoned afterward.

Urban development officials apparently plan to address unauthorized constructions contributing to flooding in Colombo, and a broad flood mitigation strategy involving multiple projects has been outlined. These include improving drainage systems, real-time flood control data centers, and various urban infrastructure enhancements, aiming to mitigate future flood risks through a phased approach. With proper management, flood disasters do not have to be catastrophic, now, or in the future.

The writer is a graduate of the Faculty of Engineering, University of Peradeniya. He has a Ph.D. degree from Colorado State University and is a Research Professor at Florida International University in the United States. He received the 2015 Norman Medal of the American Society of Civil Engineers for a technical paper that makes a definitive contribution in engineering. He was a member of the US National Committee which developed the 2014 National Climate Assessment.

Leave Comments