BUILDING A CONSTITUTION: CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES CONFRONTING TROUBLED JURISDICTIONS

Address by Mr. Rajeev Amarasuriya in the Session on Building a Constitution : Constitutional Challenges Confronting Troubled Jurisdictions at the 35th LAWASIA Conference held in Sydney, Australia

Most if not all Jurisdictions from time to time will face Constitutional Challenges, in my understanding it is more akin to a cycle which most go through at one time or another, and this discussion therefore is pertinent not only to those from countries presently facing issues, but also to everyone else to be mindful of the threats and challenges our system is open to.

- Introduction

Human nature is such that it is only during or after a heavy storm that we find the need to check our pipes for leaks. Never beforehand, as should ideally be the case.

Likewise, as now well known to the rest of the world, Sri-Lanka is currently emerging from a turbulent period, and now more than ever, assessing our legal and constitutional framework to ascertain where the leaks are.

The uncontested notion of supremacy of the constitution could now be viewed as a concept that has become a universal norm.

Just as how civilizations rely on laws for regulation and order, laws can be seen to rely on the constitution to maintain its integrity and preserve its functionality. Laws by itself are merely sets of rules.

What gives these laws effect resulting in state and civil obedience is the structure drawn out by the constitution of a State. This places the constitution above all laws, the superior law, the instrument of checks and balances necessitated for a functioning system.

This is also why the discussion of constitution making holds immense value. The considerations, factors, discussions, taken into account to weave the fine threads of a constitution shoulders the fate of a state’s governance.

To narrow down the scope of this discussion to fit productively into the time frame I have been allocated, my main focus would be discussing the concept of constitution making alongside the evolution of the constitutional framework of Sri Lanka.

- Constitutional History of Sri-Lanka

Sri-Lanka is currently under the 2nd Republican Constitution of 1978 and that too with its 21 amendments.

Spanning from the time that the British captured Sri Lanka (which was then known as Ceylon) there has been many reforms which have led to the current constitution.

Constitution making does not simply embody the formation of a single constitution, but embraces the entire process and history of development of a constitution. It took many significant constitutional reforms to ‘make’ the Constitution of Sri Lanka what it is today.

It wouldn’t be incorrect to say that constitution making requires some trial and error, and countless failures in order to grow and flourish in the right direction.

The British captured Ceylon from the Dutch in 1796 and between 1789 and 1801 Ceylon was administered under a system of both the Governor and the English East India Company as the dyarchial authorities.

With the conquest of the Kandyan Kingdom 1815, the British had conquered the entire island, being something which neither the Dutch nor the Portuguese could do.

The Colebrooke Commission Reforms of 1833 which is recognized as one of the first significant constitutional reforms established the Executive and Legislative Councils for a unified Ceylon and replaced the rule of the Governor and his advisory council.

In 1923 further reforms resulted in an increase in the composition of the Legislative Council. But the drawback was that no mechanisms were created to establish a connection between Executive and Legislative councils as Legislative councilors that were elected to the Executive council had to forego their seats to the Legislative council on appointment.

This imbalance called for the Donoughmore Reforms of 1931 commonly The Donoughmore Constitution). The objective of this was to transfer complete control to the Ceylonese elected representatives, over their internal affairs subject only to the reserve powers and the exercise by the Governor of certain safeguarding powers.

The granted Soulbury Constitution of 1947 was a step forward from its predecessor and introduced many features such as the Westminster model of Parliamentary - cabinet system, Bi- cameral legislature, parliamentary sovereignty, Judicial review of legislation and preserving the independence of judiciary. However, it was criticized for inadequate provision for human rights.

This was rectified to a certain degree by the introduction of the first republican constitution of 1972, however it also weakened concepts such as independence of the judiciary and focused on strengthening parliamentary sovereignty in a manner that diminished the balance between state organs.

The present Constitution in 1978 introduced an Executive Presidential system where the President is the Head of State and also the Head of Government with a Parliament from which a Prime Minister and a Cabinet of Ministers is formed.

On paper, the system imposes many checks and balances between the three organs of government, that is the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary, to create a happy balance.

However, from the very inception of the Presidency and for many of the years, the reality has been where the Executive President is also the Head of the Political Party that forms a majority in Parliament and the party of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet of Ministers.

Consequently, the check the Parliament should have on the Executive breaks down, and this was further exasperated by the fact that appointments of members to the higher judiciary was also by the President.

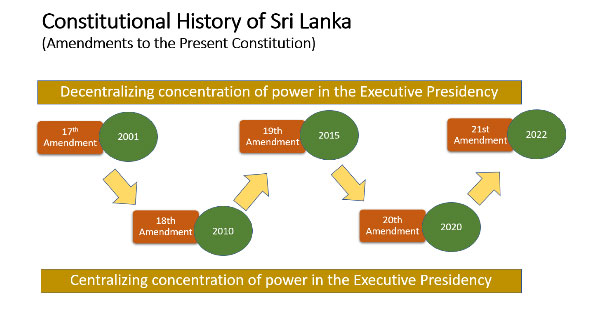

It is in this backdrop that the Parliament at the time in 2001 brought in the 17th Amendment to the Constitution, introducing many checks, balances and controls on the Executive, especially in respect of appointments of senior officials. In substance, the 17th amendment is praiseworthy mainly due to its careful construction of the Constitutional Council which included civil society representation, however its downfall was caused due to extreme drawbacks in terms of implementation.

The Presidents’ refusal to make due appointment of the election commission marked the beginning of the failure of the 17th Constitution. This crisis was deepened in March 2005 when the first term of office of the first Constitutional Council expired and no new appointments were made to the council.

However, with a change of Government, the 18th Amendment reversed the progressive changes in 2010 and could be perceived as another decisive step in the centralisation of power in the executive. It replaced the Constitutional Council set up by the 17th Amendment with a weaker Parliamentary Council and therefore compromised some of the important checks on executive power set out by the 17th Amendment.

Further, prior to the bill being placed before the parliament there were no public announcement concerning the constitutional change.

The changes was rushed through as a bill ‘urgent’ in the national interest. Therefore, there was a violation of the basic principles and norms of constitutionalism and constitution making.

The changes brought forth by the 18th was once more reversed by the 19th Amendment in 2015. The main aim was to curb the powers given to the executive by the 18th amendment, and by doing so, reinforce democracy in the country. As such the Constitutional Council was once again constituted to effect such necessary checks.

However, in 2020, upon a change of Government, the Constitution was once more amended strengthening the powers of the Presidency, and it was with these powers that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa had to resign.

Interestingly, his successor President Ranil Wickremesinghe, once more under his direction, recently introduced the 21st Amendment reducing some of his powers as President and once more, reinstating the Constitutional Council.

- Current Events

Sovereignty is a political concept that refers to the dominant power or supreme authority. We as the people are made sovereign by our constitution, however that does not mean we could do whatever it is that we please. There needs to be a certain order and decorum maintained for peace to be sustained.

Ones right can only be exercised in a manner that does not impede upon anothers’. It is the respect for the law, the rule of law that maintains these checks. A respect granted through the Constitution, but regardless something that would only be sustained through the will of the people.

The recent economic and political crisis caused a severe strain upon the rule of law in Sri Lanka. What would come to be known as the revolutionary ‘aragalaya’ (the enormous protests of the citizens) amplified the cries of the vast number of people severely affected by the crisis.

On one hand this was a cry to voice out grievances, for the peoples’ struggles to be acknowledged and on the other it was a demand for change, accountability, transparency, and furthermore a demand for a plan that would map a way out and towards a better future.

Midst the havoc it became more and more difficult to imagine a way that normalcy could be restored.

One such step would be effecting the 21st amendment to the Constitution. A force of a hand, one may say, necessitated by the dissatisfaction and uproar of the mass majority. A beautiful way to move towards constitutional change, as a reflection of the will of people rather than being one at the behest of partisan politics, endlessly reversing and effecting previous amendments to suit those who are in the driver’s seat.

There was also a popular call that the Members of Parliament had lost their mandate to govern. However, Sri Lanka does not have a system that could recall a Member of Parliament and the only lawful and constitutional way would be to select new representatives through the ballot, and this would have to be seen in the future, hopefully sooner that later, which would then pave way for the regularization of what has taken place in the last one year.

- Concluding Remarks

It can be concluded that constitution making, at least in light of the Sri Lankan context has always been more about the journey rather than the destination.

Every state goes through its own process, and factors such as interpretation, spirit and the will of the people shape the journey and weigh heavily upon the success of a Constitution.

In the end of the day, constitutional making in theory are just words upon a substance no matter how cleverly or craftily sown together, the effect of which cannot be assessed at the point of making but only through the experience of implementation.

Therefore, one may not disagree that the best, and only teacher for the process of constitution making is the history left behind by the flaws of its predecessors.

** Also;

Photo and a relevant Slide from Presentation included.

-

Still No Comments Posted.

Leave Comments