Keep the numbers high

Reducing Sri Lanka’s armed forces drastically in terms of combat-ready personnel is dangerous!

By Dushyantha A. Basnayaka

One of the topics that have attracted widespread attention in the media recently is the size of the SL armed forces. We saw in recent months some politicians, journalists, retired generals turned security analysts, political analysts, academics, activists and influencers alike so eloquently raise their voices suggesting to reduce the size of the SL armed forces.

Dr Dayan Jayatilleka, a political analyst, regularly voices concerns about the size of the SL armed forces in his regular columns. In 2021, Prof. Rohan Samarajiwa, an academic-turned-social activist, citing Costa Rica, went further and even alluded to the idea of disbanding SL armed forces. More recently, a retired general-turned-security analyst, Boniface Perera, arguing against excessive defence spending and citing analysis from foreign experts, proposed what he called “right-sizing” of SL armed forces, especially the SL army. According to him, “… the threat perspective was very minimal at present other than an uprising of the local population against the Government…” This appears to implicitly suggest reducing the size of the SL army drastically.

The common denominator of all these analyses is the notion that in the presence of significant economic hardships and while a significant fraction of people are suffering in many ways, maintaining a large armed force, on the one hand, is unsustainable, and on the other hand, is morally unjustifiable. The writer does not suggest that all these experts are wrong and have ulterior motives. The arguments of these experts are not without merit. However, one important dimension is completely missing in their analyses.

At this juncture, reducing the number of combat-ready personnel in the SL armed forces is dangerous. The number of armed personnel, who can be called for duty at short notice, should be kept as high as possible. This does not necessarily mean that the expenses of the SL armed forces should be continued at the current rate, or be increased. Every step should be taken to optimize the security expenses, and where possible, even to reduce the expenses. In addition, the armed forces may augment their income by contributing to international peacekeeping missions. While keeping its numbers high, the armed forces should optimize their expenses, observe utmost discipline, and also should never show undue aggression to the public either in the North or the South. But why?

It is about deterrence

When so many experts are advocating with rather elaborate arguments for reducing the size of the armed forces, a serious justification is needed as to why the SL armed forces should keep their numbers high.

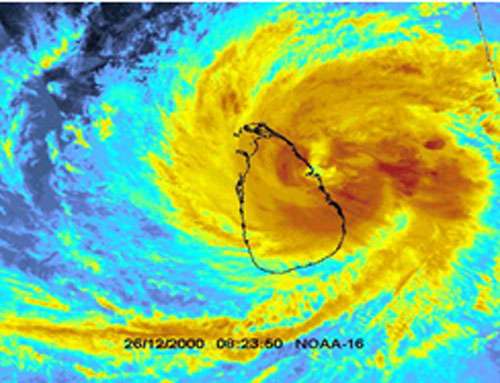

There are two kinds of threats: imminent and non-imminent threats. We do not intend to do a detailed threat analysis here, but due to being a nation located in strategically important waters and the lack of a properly functioning strong central government, Sri Lanka is engulfed with threats. Sri Lanka needs a sizable armed force in terms of personnel not to fight, but to avoid potential fights in the future. Because, a sizable, well-trained armed force, even with a low level of technological sophistication, has the effect of deterrence, if used prudently. The lower the technological sophistication, typically the higher the number should be. The deterrents can be used for shaping the thinking of potential groups and countries who could pose threats, so conflicts can be thwarted even before they see the light of day.

Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake

In 1947, Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake signed a defence pact with the British and allowed the British Royal Navy and Royal Air Force to be stationed in Trincomalee and Katunayake. Many at the time and later interpreted this agreement from different perspectives. After ascending to the premiership in 1953, John Kotelawala even stated that ”… the more British warships could visit Ceylon the better it would be”. Many Sinhalese and Buddhist factions voiced significant reservations about this defence pact, and they indeed seem to have had good reasons to oppose this defence pact. It is not known exactly what was in the minds of Senanayake and Kotelawala when they signed this defence pact. A detailed debate is left to historians, but this defence pact served one important thing. It functioned as a deterrent.

Deterrence is an important element in national security. At the time, Soviet influence in the region was great, and India was considered a threat. DS might also have had concerns about safeguarding the authority of the newly elected parliament from potential local aggressions too. The 1st parliament in 1947 largely comprised low-country Sinhalese and Tamils, who achieved prominence very recently, and to a larger degree thanks to the British. They might have especially been concerned about the Kandyan chieftains disenfranchised by the British, and also the rise of Marxism.

Even though it is difficult to support all of his policies, Premier Senanayake understood clearly the enormity of the defence challenge when transitioning from one authority to another less established authority. He made his view clear when he said, "... the defence of the country (referring to Sri Lanka) is one of the primary obligations of an independent state….Frankly, I cannot accept the responsibility of being minister unless I am provided with means to defence.” Without sufficient defence arrangements, the transition from colonial powers to locals could easily lead to chaos.

Lack of deterrence is begging for troubles

The fall of Patrice Lumumba of Congo, one of the most naive politicians in the modern era, teaches us the danger of not having sufficient deterrence. Lumumba was elected prime minister of the independent Congo in May 1960. He had the constitutional authority but did not have the real authority over the populace. He offended many people in his first speech as prime minister and had no sufficient means to deter potential aggressions. Within weeks, he saw a series of secession movements and rebellions supported by factions of the army and the colonial power, Belgium. Within months, he was captured and executed by the separatists, and the country plunged into chaos.

President Jayewardene and Minister Athulathmudali

The spectacular fall of President Jayewardene in 1987 is emblematic of Sri Lanka’s modern history, and can be largely attributed to Sri Lanka’s lack of deterrence. About a year ahead of the signing of the Indo-Lanka accord in 1987, President Jayewardene replied to a question from an Indian journalist with “…If the Government of India wants to invade us, which I am convinced they will not, they can take over Sri Lanka in less than 24 hours and arrest me….” A leader, who had all the constitutional power and was in charge of the country’s security for nearly a decade, was making these comments is simply incomprehensible. At the time, it was Lalith Athulathmudali, who served as the deputy minister of defence and the minister of national security. In the mid-80s, SL armed forces were small in terms of personnel and lacked modern technology and advanced training.

Since the landslide victory in 1977, President Jayewardene did not have the time to focus on deterrence, because he was busy intimidating his political opponents. Meanwhile, Minister Athulathmudali, who came to prominence due to his oratory skills, seems to have believed that intrastate and interstate affairs can always be done by charming words and eloquent speeches only.

In 1985, referring to BBC and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s recent comments, he bragged about how his efforts had enabled Sri Lanka to win the world opinion. Also in 1985, to a cheering crowd from a diaspora organization in the UK, Athulathmudali said how he tried to persuade American newspapers for two-three hours to change their views on Sri Lanka’s war against terrorism. He seemed to have assumed the role of a foreign minister, but, at the time, he was the deputy minister of defence of Sri Lanka. His choice of priorities was far from ideal and added credence to the claim that he may not have understood the gravity of his main role at a difficult time in Sri Lankan history. Both President Jayewardene and Minister Athulathmudali had a background in non-exact sciences, and appear to not have had a good understanding of the concept of deterrence, how to increase the deterrence capability of a country, and more importantly, how to use it prudently.

In light of the then leaders’ naivety, Prime Minister Gandhi of India was convinced that if Sri Lanka was threatened with invasion, President Jayewardene would submit. Due to Jayewardene’s autocratic rule, Gandhi was certain that people would not flock around President Jayewardene to support him, and the SL army was weak. In the absence of sufficient means to deter Prime Minister Gandhi, in July 1987 President Jayewardene had no option, but to submit. His actions eventually gave Sri Lanka the 13th Amendment

Taking chances is dangerous

Due to being located in strategically important waters, Sri Lanka is in need of a great deal of deterrence. The technologically advanced nations can reduce their armed forces, because in some cases, but not always, the technology can be used to compensate for personnel. However, reducing the number of personnel beyond a certain point is dangerous even for sophisticated armies. In early 2023, media reported that a US general has warned the British Army that it was no longer a top-level fighting force, and to halt plans to shrink the size of the armed forces further.

Sri Lanka should continue maintaining a sizable army until such time that visionary people take the leadership of the defence matters of Sri Lanka, and modernize the deterrence capabilities of SL and SL armed forces considerably. Sri Lanka should not take any further chances, because destruction, submission and subjugation have been a part of its existence for too long.

(The author, an engineering professor, born and bred in Sri Lanka, is currently based in Dublin, Ireland. Before that, he was with the School of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh, UK. He graduated from the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Peradeniya with first-class honours. He can be contacted via email at dushyantha.basnayaka@gmail.com)

-

Still No Comments Posted.

Leave Comments