By Saritha Irugalbandara & Nishadi Gunatilake

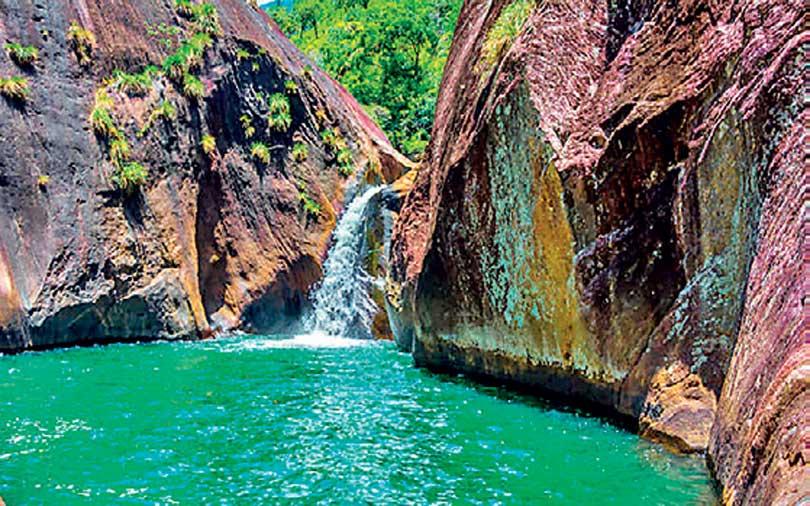

Pahanthudawa is a scenic waterfall in Belihuloya, Ratnapura, named after its distinct clay oil lamp shape. The relatively clandestine little fall has achieved unprecedented notoriety due to the infamous pornographic video that is bound to transpire discussion, debate, or laughter for some time in Sri Lanka. An investigation was launched by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to arrest those who produced and published the video on a commercial pornography website. The Cyber Crimes Division of the CID provided the technical support, tracking down the parties that had uploaded it and shared it across various online platforms. Within a span of three days, this collaborative effort succeeded in arresting the suspected couple, who have since been released on bail.

Sri Lanka Police sprang into action to arrest the couple appearing in the video following mounting pressure from the public about the “indecent” video. It is an understatement to say that the video garnered significant traction on the local cyberspace. Pahanthudawa was trending across all social media platforms, the video itself was widely shared on personal messaging apps such as WhatsApp, and an unofficial national conversation has transpired about the video and its impact on Sri Lanka’s ‘cultural security’. In a letter to the President, Ven. Battaramulle Dayawansha thero stressed the urgency to remove the video off the internet and warned of the repercussions of not taking expeditious action. More specifically, the thero warned that the tourists will get “the wrong idea about the Sri Lankan tourism industry” through this video. YouTube pundits have also weighed in on the issue at length, with colourful commentary on how damaging this video is to Sri Lanka’s culture, setting an unhealthy example for others on acceptable behaviour, and the perils of normalizing “indecent” behaviour for our children. Many were praising the prompt arrests as a step towards deterring such “inappropriate” behaviour by sending a strong message to those that create and share pornographic material.

Whatever your opinion on the video, the people in it, the involvement of the police, pornography, and decency, one thing is for certain -- everyone has an opinion on it. This article is but another opinion, a somewhat retrospective view of the many moving parts that are deeply revealing about the broader Sri Lankan psyche, “culture”, and behaviour.

Legal Context

While it is not publicly confirmed under which legal provisions the couple will be charged, lawyers opine that they are likely to be charged under both the Penal Code and the Obscene Publications Ordinance.

Section 285 of the Penal Code makes selling or distributing, importing, or printing for sale or hire, or publicly exhibiting any “obscene content” an offence, while Section 286 makes the possession of such content for sale, distribution, or public exhibition an offence. Section 2 of the Obscene Publications Ordinance essentially covers the same elements, with the notable addition of the making or producing ‘obscene content’ also being made an offence. Despite the word pornography never appearing on either laws, they have been applied to criminalise pornographic content. None of the legislation explicitly defines what constitutes “obscene”, leaving a wide berth for interpretation. Ideally, this should be up to the judiciary -- however, the nature of the Sri Lankan criminal justice system is such that the police often become the first interpreter of the same.

It is common procedure for couples in Galle Face or Galle Fort to be intimidated and arrested for holding hands, and people of the opposite sex, not exclusively couples, that sit close to each other at Independence Square to be reprimanded by the police due to “obscene” behaviour. Violence, too, is obscene and could have a victim, but it is not policed with the same vigour as victimless behaviour such as holding hands in public. In fact, Senior Deputy Inspector General of Police (SDIG) Ajith Rohana recently stated that police in Sri Lanka do not intend to carry forward cases of “slight assault”, abuse, or threats between husband and wife to a court, as such matters tend to be reconciled between partners in the respective police stations. Elaborating further, he mentioned that unlike European countries, Sri Lanka has its own culture, value, and ethics. The SDIG’s statement may be seen as an admittance of selective policing of behaviour within the ambit of private life in Sri Lanka.

In the absence of an in proviso definition, it may be possible to refer to Black’s Law. “Obscene” is thus defined as anything that is ‘indecent’ and ‘calculated to shock the moral sense of man by a disregard of chastity or modesty’. Subjectivities on nudity and displays of sexual activity mean that commercial pornography, created by consenting adults, can be seen as obscene by some. This is especially true if the content exists outside of an ‘appropriate’ context such as an adults-only website. It does not mean sex itself is obscene. A ‘shock to the moral sense’, however, would require a definitely immoral element to be present to qualify something as ‘obscene’ within the meaning of the law. As far as the porn industry goes, non-consensual and ‘revenge’ porn and child abuse and exploitation fall far closer to this definition than two adults having consensual sex at a waterfall. The Pahanthudawa video was also only intended for a commercial pornography site, which means that the parameters of chastity and modesty can’t reasonably apply.

There are also many other questions on how the laws on obscene publications are subjective and selective. As far as the online space goes, the evidence lies in the thousands of groups and pages on Facebook that routinely distribute images of women and children for sexual exploitation, somehow evading the keen police radar that managed to track down everyone involved in the Pahanthudawa video in a matter of days. It should also be noted that the commercial pornography websites that this video was uploaded to, also hosts thousands of non-consensual clips of Sri Lankan women and children, free to be accessed by all, and distributed with alarming regularity on social media channels and WhatsApp groups. These publications are certainly calculated to shock the moral sense of an average person, and blatantly disregards principles of modesty. However, the public outcry and expeditious crackdowns are neither routine nor expeditious for the latter. The disproportionate curiosity for the private lives of consenting adults as opposed to the prevalence of abuse and violence is symbiotically produced by the police and public.

Law enforcement may sometimes approach the law as an all-knowing arbiter of what is right and wrong, which is a regressive approach. Popular literature and art in Sri Lanka makes ample reference to the colonial era laws that imposed taxes on “everything but the milk in a mother’s breast”: morality and law are not always mutually exclusive. Archaic legal provisions such as in the Obscene Publications Ordinance must be investigated as moralities that once existed may be changing in society. Laws should evolve to accommodate social and political changes instead binding people to the notion that the law, no matter when or why enacted, is absolutely equal to morality.

Expression and public spaces

The second set of legal principles, albeit not formally applied to this case, pertains to the legality and “appropriateness” of sex in a public place. It must be noted that as there are no specific legal provisions prohibiting sexual activity in a public place in Sri Lanka, any charges would have to rely on the amalgamation of several separate provisions. This was also invoked by the public both online and offline, who speculated that the public setting compounding the “indecency” and “obscenity” of the video.

Section 365A of the Penal Code criminalizes “acts of gross indecency” in a public or private space. The definition of gross indecency is still open for interpretation.

As mentioned above, this could include young couples kissing or holding hands in public, including in some cases while inside a personal vehicle. There are also many stories of the police using 365A to intimidate people suspected of being LGBTIQ+, including unauthorized questioning about their private sexual relationships. These decency laws, introduced by the British colonizers, have a long history of being used to suppress and discriminate against women and LGBTIQ+ people in the name of preserving “culture”. The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, in 2016 held that these public morality laws imported by colonial rulers are incompatible with contemporary thinking, and that “consensual sex between adults should not be policed by the state nor should it be grounds for criminalisation”. However, the long umbilical cord between colonial laws of morality and existing local laws and their interpretation continues to nurture a collective denial about the extent to which we continue to embrace Victorian ideals from the past as our own culture.

Many people offline and online propose that strong punishment was warranted for sex in public as it could have been witnessed by others that did not consent to being exposed to it. Arguably, if this video was shot in plain view of non-consenting members of the public, this would constitute a criminal offense, where a clear victim can be identified. While hypotheticals like this are superfluous as far as fuelling misplaced outrage goes, the lack of a third party -- a victim -- that was subjected to the scenes at Pahanthudawa without consent makes this argument pertaining to gross indecency farfetched. What is also interesting is how plenty of women and children in this country will attest to being flashed genitalia in public spaces without their consent, with alarming regularity. However we do not see these forms of sexual harassment being normatively identified as acts of “gross indecency”, nor do we see any urgency on the part of the police to eradicate such behaviour. It is clear then, that the reference -- and therefore the penalisation -- is to any voluntary, agentic expressions of sexuality -- explicit, implicit, and sometimes imagined.

Most people came across this video through hashtags, forwards, and by accident while scrolling social media -- spaces the video was not originally intended to occupy. This has undoubtedly been uncomfortable for many unsuspecting users, many of whom felt they were victimised by this video that they were ‘subjected to without consent’. ‘Consent’, on a social media timeline that is determined by algorithms and digital proximities, is largely governed by the terms and conditions of agreement between the social media company and users. Popular networking sites have complete agency on what makes it to your timeline - and what doesn’t. Facebook blurs out ‘sensitive’ content, regularly removes symbols of female nudity, and YouTube places age-restrictions on ‘adult’ content. As far as seeing this video on your timeline goes - as alleged by many people - the responsibility lies with social media companies and what they give visibility to. Culpability, from a subjective or personal standpoint, may also fall on those who shared this video on spaces that aren’t exclusively adult-only, and this includes YouTubers who used censored clips of the original video as a preface to their commentary. What is undeniable is a lacuna in the law on how to address situations where users come across potentially offensive or sensitive content by chance. The intention of this piece is not to downplay any distress people may have experienced due to being shown or forwarded the pornographic video without consent. The transgression of boundaries in this way on digital platforms, especially with regard to non-consensual sharing of pornographic or graphic material, is a serious form of harassment - one which disproportionately targets women and girls. However, the ‘blame’ if any, should then fall on anyone who forwards you sexual content without your consent; to direct anger at the couple who appeared on the video, who had no control over how the video would be shared, is like cutting the nose to spite the face.

Within this outrage was also the notion that if this couple was not reprimanded it would be normalising public sex, an especially dangerous precedent to set for young people. This brand of speculation misses two important points about sexual activity in public places - especially where youth are concerned. The cinema halls across the island, nooks and crannies of the Racecourse pavilion, the gazebos at Viharamahadevi Park and the rearmost seat of public buses have countless stories to tell, featuring giddy young people finding privacy in public spaces. There is much we will leave unsaid about glass houses and throwing stones. The fear of normalization is a misplaced one if the behaviour is already commonplace. The sexual hypocrisy at play is deeply internalized. If there is anything Sri Lankans can unify on, it is the harassment and judgement of those whose behaviour are mere degrees of separation away from our own to satisfy the need for a sense of moral superiority.

The personification of dulture

In 2021, Sri Lanka continues to be the country with the highest number of Google searches of the word “sex”. The word ‘sex’ itself is a taboo in broader Sri Lankan society, however, and a multitude of euphemisms and colloquialisms exist to refer to it. The relative privacy afforded to us on digital screens juxtaposes poetically against how the same digital footprint disrobes our cultural hypocrisy.

Between the 29th of August and the 12th of September, 3376 unique public Facebook posts included the word Pahanthudawa in Sinhala, Tamil, and English. On Facebook overall, the word appeared 12026 times on publicly visible content. The term was mentioned 1548 on YouTube within the same two-week period. This does not take into account discourse with no mention of the word Pahanthudawa, misspellings, or the countless private conversations that were had online, a majority of which would certainly involve some discussion about the cultural implications of the video.

The clergy -- the most influential being the Buddhist clergy -- are the self-appointed protectors and gatekeepers of ‘culture’ in Sri Lanka. All institutional religious sects in Sri Lanka enforce certain metrics of decency that laypersons are expected to follow, predominantly directed at women. From comprehensive sexuality education to what is “appropriate” behaviour for “respectable” women, it is peculiar that we turn to a sect that is sworn to celibacy as an authority on all things sex and sexuality. What is particularly interesting about the clergy’s involvement in the Pahanthudawa situation is the comment about the apparent detrimental effects on tourism. Even though an overused comparison at this point, it is amusing to hear that a single commercial pornography clip would be the nail in the coffin for an industry that has long profited off the selling and romanticisation of the topless apsaras at Sigiriya.

Aside from this, the public response was also deeply revealing. Almost everyone had a say, ranging from people who were boastfully stating that they have seen better porn, to those who were saying it is a shame to the country and its culture. Some others also observed that porn could be the latest way of generating much needed foregin exchange. However, the most vocal were those who were condemning the video, saying that it is against our “culture”. This begs the question, what is our culture?

Any generic discussion of Sri Lankan culture actually refers to the current Sinhala and Buddhist cultural tradition, which is an imagination of what Sinhala and Buddhist life must have been like before Western influence during colonisation. This imagery looms above what might likely have been the reality of precolonial times where a sexual act involving two men and a lion was carved into a temple wall, artiste kings commissioned frescoes of life-sized naked women, and of a rich, well-documented literary tradition pioneered by Buddhist monks who described the beauty of women in excruciating detail. The compulsion to continue embracing puritanical Western colonial values has effectively bred a constant need to sexualize and objectify the expression of either. Sri Lankans are often so preoccupied with this imagined war between the “Western lifestyle” bogeyman and our “culture” that it has obscured how the latter is an achcharu of outdated ideals that Western imperialists did not take back. The personification of culture in this way tries to keep dying ways of thinking alive, and creates an authority figure on all the reasons we should be afraid of our own agency the most. And of course, the effects are not symmetrical. For all the talk of how Sri Lankan culture protects women, what the West and Sri Lanka have in common is the way the bodies of the poor, women, and sexual and gender minorities are controlled and reduced to battlegrounds for ideological wars on morality and decency.

Women’s sexuality is another imagined enemy of our “culture”, and of course curbing the same was at the forefront of the discussion too. Many people created memes which said they would marry only a woman who has not watched the video. A close read of the public response, especially from fellow women, would hint that perhaps a woman is not allowed to express sexual desire even with her husband. Many comments on Facebook stated that her body language in the video is especially lewd, that they would never have behaved in such a way with their own husbands despite being married for decades and birthing many children. It reminds us of the recent statement by a monk, that women in the past did not even see their husbands naked, and therefore their sex lives were “pure”. Perhaps this same video could have been more palatable to Sri Lankan culture had the woman been imobile for the most part.

Another popular claim was that this kind of material corrupts children. One can argue that a lot of material in the public sphere corrupts children. Teledramas that nomalize violence against women, TV advertisements that perpetuate gender stereotypes, songs that contain sexually suggestive language, domestic violence and unhealthy interparental relationships can also corrupt children. Child abuse and exploitation, including online sex trafficking and exploitation, is rampant, but the news cycle pauses after sensationalizing a selected case for about two weeks. We do not see this urgency to save the innocence of the children when it comes to those areas. It also raises the question of the extent to which content that is produced in society should be censored and sanitized so they are suitable for children’s eyes. This is not how society functions in any country, at any time. Not only is it unrealistic to expect all of society to censor itself; it ignores the responsibility of parents or guardians to ensure children do not accidentally come across age-inappropriate content. This is a normal part of child rearing and those who decide to have children in their life should make it their utmost priority to learn about these tools for themselves, and the government should facilitate adult learning programs for anyone who wants to learn these, especially parents and teachers.

Response of the media

The metrics of morality are deeply entrenched in our institutions, and the media in Sri Lanka is the primary packager and seller of these metrics. Almost all mainstream media reports did not once contain the words “sex” or “sexual intercourse” in their Pahanthudawa coverage. “Indecent video” or “naked video” were the common terminology, while some accounts referred to it as a video of “a couple behaving as husband and wife”. This self-censorship is an extension of how the State constantly polices sex and sexuality. The rationale behind treating sex itself as something inherently offensive is symptomatic of a deeper hypocrisy; to remain steadfastly in denial that we are a country obsessed with sex on digital screens, we must deflect and shift blame onto those that provide it. It is the naked people who ruin the culture, not others who watch naked people ‘behaving like husband and wife’.

Significant portions of word counts and stand-alone pieces were also dedicated to divulging the following pieces of information: the video was uploaded by a woman, her profession, her age, and that she had been making commercial pornography to earn money for a while. A spotlight was also shone on the detail that she was unmarried. Her marital status is pertinent to driving home this hypocrisy around how we view women as relative to men, where women’s expression is only appropriate in the privacy of her State-approved relationship with a man. This protracted focus on the woman is deliberate, to evoke more fear of cultural deterioration that continues to be placed on the bodies of women who exercise agency. Women who make up 52.1% of the Sri Lankan population are only represented by 5% in Parliament, and largely deemed unfit for public office, but are always tasked with adjusting their bodies for cultural preservation.

A mainstream newspaper was quick to stake its claim as the first to expose this “shocking crime which has shattered the very core of the Sri Lankan populace”. The sensationalization was seen to an even greater degree on social media and web platforms, where gossip sites released continuous updates on the status of the affair. Pictures of another couple were circulated on social media, claiming that they were the people in the video. When the disinformation was brought to light, many mainstream and web media platforms jumped at the chance of clearing their names. The rectification circus, however, was even more problematic. Misleading clickbait captions which implied they were interviewing the actual couple who appeared in the video were the norm, while the content of the interview focused on how lucky the woman, whose photo was circulated wrongfully, was to be married already, as otherwise her prospects of getting married would have been ruined, as her “image is tarnished” and her “dignity” is damaged.

The social media moral police were also working overtime, advocating for the release of the photo of the actual couple, so the wrong people will not have to suffer for their “crimes”. Another interesting development was how the media attributed false captions for the Police Media Spokesperson stating that watching the video was a crime too. The police also did not take any actions to correct it, despite rooting for new “fake news” laws for months, but rather went along with the sledgehammer approach they have been taking throughout this incident and before too. This hyperactivity of the police was in stark contrast with its lethargic approach to many other offenses, especially sexual offences. For example, the average length of a rape trial in Sri Lanka is 10 to 15 years. Out of 8702 cases related to sexual and gender-based violence filed in 2012 to 2016, 98% cases had not been given a verdict by the end of 2016. Sri Lanka had taken the first place out of six Asia Pacific countries when it comes to not punishing perpetrators of violence against women.

Conclusion

The Pahanthudawa incident has provided us with a valuable opportunity to explore broader questions about the Sri Lankan psyche related to sex and sexuality. While some would argue that there are bigger questions in the country, we should not forget that sex and sexuality too form a fundamental part of society, and of both public and private life.

Some people have even gone to the extent of saying that the view a society holds on sex is a good benchmark of its overall civility and maturity. If you are an activist reading this article, the Pahanthudawa incident could serve as the anchor for future conversations on sex and sexuality and its relationship with the State. An incident which exposes our societal attitudes about sex and sexuality, with this magnitude, without it also involving a survivor of sexual violence, might not occur for a long time again. As is evident from this incident, the media in Sri Lanka cannot be entrusted with giving credible information or analysis. It also raises important questions about the role of social media platforms, their community guidelines, and where it locates users who might happen upon sexual or ‘sensitive’ content by chance.

The unfortunate sensationalizing of this video aside, these discussions about the institutional and societal treatment of sexual expression should happen when the chance arises. If you are a general citizen of the country, we would like to urge you to proactively read up on the legal context in relation to sex in the country, and to remain conscious of how much of our contemporary ideas about decency spring from internalized, colonial prejdices about ‘morality’. If you are a parent or a teacher or someone who deals with children on a daily basis, make this an opportunity to familiarize yourself with tools that are available to help your children navigate their digital lives.

Having open conversations with children about sexuality and consent, including safe ways to explore both is vital to ensuring children can make informed choices, both online and offline. Make sure you consider violence, too, under this umbrella. If you are someone who paid at least passing attention to the Pahanthudawa video, make sure that you pay at least that much attention to the myriad of issues related to punishing sexual offences in the country. As the initial shock subsides and any talk of Pahanthudawa becomes retrospective, make room for questioning our own ideals of sexuality and ‘culture’ that we embrace without question. Let’s consider this an opportunity for growth.

Leave Comments