There is news that the contract for building an elevated highway from Kelaniya to Athurugiriya has been awarded on a BOT basis and work is due to commence soon. Building highways that crash through urban areas cause immense destruction to property, buildings and the environment to leave many disenchanted residents, fauna, flora, marshes and lakes along the way.

Owners have already been notified that their buildings will be demolished according to the road markers placed on their property. Many people, who have lived all their lives in their ancestral houses or in homes they have lovingly built will thus be displaced, relocated or compensated. Development must also have a human face to it and the psycho-social and economic impact on the lives of people must also be considered with genuine empathy.

In the Pothuarawa area, the original plan was for 3.1 km to run over and demolish more than 100 houses, and residents were naturally offended and agitated and began appealing to the authorities. It was then insensitively shifted (without the approval of the CEA or an EIA) to run over the gazetted EPA and Ramsar accredited Thalangama lake and wetlands and through more than 200 acres of paddy fields diligently cultivated twice a year by passionate farmers. There was an outcry from residents, farmers, environmentalists and the media and it seems that the decision on either route is to be reconsidered. But nothing is certain because sadly, there is no real interactive dialogue with residents.

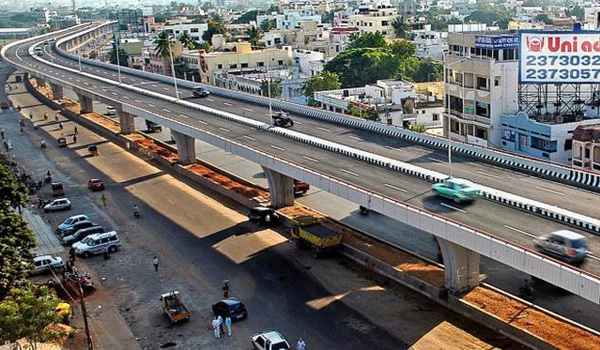

Routing the elevated highway over existing main roadways (as the photo shows) from Rajagiriya to Athurugiriya, as widely seen in India and Thailand, can avoid or mitigate the demolition of residential housing and also help preserve the Thalangama wetlands. The benefits of wetlands and how wetlands make cities liveable have been well documented elsewhere. Note that just one centre column can support a 4 lane highway so very minimal space is used on the existing road.

The issuance of Green Bonds to finance the extra costs of a different route can then be considered. A Green Bond is a type of fixed income instrument that is specifically earmarked to raise money for climate and environmental projects such as pollution prevention, protection of ecosystems, clean water, fisheries and forestry. Green financing presents a collection of tools and approaches that could be integrated into early stages of the designs of such projects and to aim not to just mitigate, but completely avoid impacts on the environment.

In a year characterised by uncertainty, green bond issuance rebounded in 2020 to reach a record-breaking USD269 billion by the end of the year. The USA led the rankings (USD51.1bn), Germany was second (USD40.2bn) and France third (USD32.1bn), China fourth (USD17.2bn) with the Netherlands fifth (USD17.0bn). Saving the Thalangama Wetlands from this highway thus gives Sri Lanka the opportunity to demonstrate the use of green financing by engaging a combination of local, national and international investor stake holders.

My knowledge of finance is minuscule but I happened to stumble upon some valuable insights by Dr Natarajan Ishwaran, a former Director of Ecological and Earth Sciences in UNESCO. Presently, he is a Scientific Committee Member of the Chinese Digital Belt and Road Programme and a Fellow of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for collaborating with the Chinese Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR) on ecosystem restoration initiatives.

I do hope the Government (and the Chinese Contractor) will seriously consider Green Bonds to cover extra costs needed to balance conservation and development needs, involving a multi sector, multi stakeholder approach.

Jomo Uduman

Etul-Kotte

Leave Comments