Latest review by World Heritage Conservation Outlook Assessment

By Professor Emeritus Nimal Gunatilleke

IUCN World Heritage Conservation Outlook Assessment on Sinharaja natural World Heritage Site (https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/explore-sites/wdpaid/16791)

The IUCN World Heritage Conservation Outlook Assessment in its latest assessment cycle of 252 global Natural World Heritage Sites (released on 09 December 2020), has assessed Sinharaja Natural World Heritage Site (SNWHS), the icon of biodiversity conservation in Sri Lanka, as "significant concern". What it simply means is that the site’s conservation values are threatened and/or are showing signs of deterioration. It recommends that significant additional conservation measures are needed to maintain and/or restore values over the medium to long term.

It is, indeed, not a satisfactory report card even before the more recent conservation issues hit the headlines of the national news media.

The IUCN World Heritage Outlook regularly assesses the conservation prospects of all natural World Heritage sites: designated as such because they harbour irreplaceable ecosystems and provide habitats critical to the survival of globally threatened species. It identifies the most pressing conservation issues affecting natural World Heritage sites and the actions needed to remedy those issues, thereby informing the international community, including IUCN, its Members, and partners. IUCN’s assessment shows whether current conservation measures of a given site are sufficient, if more must be done, and where.

Examining the successes and challenges of preserving these landscapes of ‘Outstanding Universal Value’ is an indicator of the effectiveness of protected and conserved areas. It comes at a time when the international community seeks to measure progress towards global biodiversity targets and defines the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. These sites are globally recognized as the most significant natural areas on Earth and their conservation must meet the high standards of the World Heritage Convention. Our ability to conserve these sites is thus a litmus test for the broader success of conservation worldwide.

Outlook Assessment of Sri Lankan Natural World Heritage Sites

The IUCN has been conducting this global assessment of natural (and mixed) world heritage sites using standardized methodology for protected area assessments, once in every three years, since 2014. As such, the first cycle of assessment was carried out in 2014, the second in 2017 and the third in 2020. The results of the current World Heritage Outlook 3 (in November 2020) indicate that for 63% of all sites (159), the conservation outlook is either ‘good’ or ‘good with some concerns’, while for 30% (75 sites including both Sinharaja and the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka), the outlook is of ‘significant concern’ and for 7% (18 sites) the conservation outlook is assessed as ‘critical’.

The outlook assessment makes a detailed assessment based on the evaluation of three main criteria i) Current state and trend of values of the World Heritage Property, ii) overall threats and iii) overall protection and management. The 2020 outlook assessment has placed Sinharaja WHS in the data deficient and low concern for current state and trend of values (no. i above) suggesting that since new discoveries of plants and animals are still being made, its true biodiversity value is yet to be realized, but it is of low concern. However, its assessment of overall threat (no. ii above) is in the High Threat category due to continued reporting of incidents related to i) encroachment of forest due to agricultural expansion (e.g., tea small holdings), ii) illegal gem mining, iii). deliberate fires, especially in the eastern theater, iv) human dwellings, v) mini-hydro projects, vi) poaching, vii) cardamom cultivation in the natural forest, viii) unsustainable tourism developments, ix) fragmentation due to road construction, x) spread of invasive species and illegal collection of rare and endemic species for international trade.

The Outlook Assessment 3 also states that xi) overuse of agrochemicals in tea plantations bordering the forest can lead to the pollution of streams and rivers and associated aquatic biodiversity, xii) increased visitation beyond carrying capacity during peak seasons and xiii) development of tourism infrastructure are impacting negatively on forest and freshwater ecosystems. These threats, if continued with a ‘business-as-usual’ frame of mind, could seriously compromise the conservation of Sinharaja World Heritage site in the future.

The Outlook Assessment recommends that the management authority i.e., the Forest Department of Sri Lanka needs to take immediate steps to implement a plan of action to address threats and fill management gaps. It places its well-guarded optimism that some of these concerns would be addressed through two recently initiated projects - National REDD+ Investment Framework and Action Plan (NRIFAP) and the World Bank funded Ecosystem Conservation and Management Plan (ESCAMP). The IUCN World Heritage Outlook Assessment believes that with the implementation of the ESCAMP project in accordance with its stated objectives, a 'Sinharaja Management system' has been instituted at the Ministry of Environment by the Forest Department to address all issues related to its sustainable management.

It is, indeed, the wish of conservation conscious citizenry of Sri Lanka and the world at large that when the next cycle of assessment comes round in 2023, the Sinharaja Assessment indicator would be moving towards ‘Good with Some concerns’. With the efficient implementation of the ‘Management Plan for Sinharaja Rain Forest Complex’ which is being under preparation at the present moment with financial and technical support from the ESCAMP project, it is hoped that the above threats could be minimized and consequently, the conservation outlook of the Sinharaja World Heritage Site would improve, significantly.

Potential threats to Sinharaja since Outlook Assessment 3

The IUCN World Heritage Outlook Assessment 3 was released on its website in November 2020. For Sri Lankan World Heritage properties i.e., Sinharaja and the Central Highlands, information gathering for this exercise started more than a year ago consulting a host of experts knowledgeable on the two properties both within and outside Sri Lanka. However, none of the recent events that hit the headlines of national news media such as i) Lankagama road project, ii) possible obstructions to the elephant migration patterns and iii) construction of reservoirs within the newly declared Sinharaja Rain forest Complex were included in this assessment. These, along with many other threats, their impacts and mitigatory measures adopted would be assessed in the Outlook Assessment 4 in 2023.

One of the most recent major concerns that was raised by both national and international environment-conscious public is the potential threat to the recently gazetted ‘Sinharaja Rainforest Complex’ from the proposed Gin-Nilwala Diversion Project (GNDP). The multipurpose development of Gin, Nilwala and Kalu rivers has been initiated way back in 1968, under the ‘Three Basin Development Project’ proposal made by the Engineering Consultants Inc. (ECI), Colorado, USA.

The present Gin-Nilwala Diversion Project is proposed as a multipurpose development project to fulfill the water requirement of Greater Hambantota Development Area, meet the irrigation deficit of Muruthawela and Walawa systems and introduce commercial agriculture developments, ostensibly by diverting ‘excess’ water from the upper reaches of the Gin-Nilwala basins to SE dry zone during the SW Monsoon period.

Among the added benefit claimed by the project proponents are i) the regulation of the flooding of the downstream areas of the Gin-Nilwala basins (flood mitigation at Neluwa & Pitabeddara), especially during then SW monsoonal period and ii) road and infrastructure development from Neluwa – Lankagama road (15 km), Lankagama – Deniyaya road (14 km) and minor roads in Madugeta, Kotapola and Ampanagala areas. (http://irrigationmin.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2019/new/Project%20Details%20to%20web%20(GNDP)%20English.pdf ).

Geological investigations of the GNDP, for most part, have been completed by May 2019 and revised feasibility studies on the locations of the dams, weirs and tunnel traces have been carried out based on detailed geo-engineering investigations that involve geological and structural mapping, core drilling, geomorphological, hydrogeological, and geotechnical investigations.

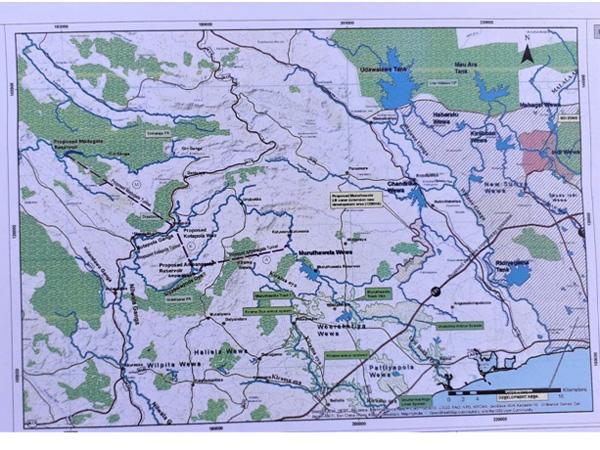

The Gin-Nilwala Diversion Project design, based on publicly available information as at present, consists of two concrete dams, a fixed weir and three trans-basin canals. The proposal of the project includes a Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC) Dam across the Gin Ganga at Madugate at the upper reaches of Gin Ganga with a diversion tunnel up to Kotapola to transfer the water from Gin basin to Nilwala basin. At Kotapola, it has proposed a concrete weir across the Nilwala Ganga with a diversion tunnel up to Ampanagala to transfer water from Kotapola to Ampanagala reservoir. At Ampanagala another RCC Dam is proposed to be built across Siyambalagoda Oya, which is a major tributary of Nilwala Ganga with a diversion tunnel up to Muruthawela to transfer water from Ampanagala to Muruthawela (Figure 1).

The project system is Madugeta Reservoir→ Madugeta Tunnel→ Kotapola Weir→ Kotapola Tunnel→ Ampanagala Reservoir→ Ampanagala Tunnel → Muruthawela Reservoir.

Figure 1. Gin-Nilwala-Diversion Project. Locations of reservoirs, weir, tunnel and canal traces. Note the proposed Madugeta reservoir inundates lands on Sinharaja and Dellawa forest areas

Water diverted from Ampanagala reservoir to Muruthawela will be used to meet the irrigation deficit of Muruthawela and Kirama Oya systems and balance will be transferred to Chandrika wewa through existing LB canal of Muruthawela scheme up to 13.8 km and a new canal of 17.0 km. After that, the water requirement of Hambanthota harbor is to be transferred to Ridiyagama tank through the Walawe river and Liyangasthota anicuit. However, due to the extreme length of the diversion through the three river basins of Nilwala, Kirama Ara and Urubokka Oya, it will lead to massive conveyance losses of the diverted water while on the way to the Walawe basin. Furthermore, enormous costs associated with its construction, a failure to fully realize the intended outcomes due to a shortage of water budget will simply be a burden that Sri Lanka cannot afford with her current economic condition, according to Eng. Prema Hettiarachchi. It may be worth recording that the water ingress into the grouted tunnel of the Uma Oya near Ella has still not been fully repaired, even though the Uma Oya project is nearing completion. An expensive lesson to be learnt on the nature of the weathered geological structure, lineaments and implementing its unexpected and costly mitigatory measures which will eventually to be paid back by this and future generations of taxpayers of this country.

According to the Irrigation Department web site postings, Mahaweli Consultancy Bureau has initiated the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA), but due to the unavailability of concurrence of the Forest Department, revised TOR has not been issued by the CEA. Therefore, due to the unavailability of updated TOR, the EIA study has been delayed.

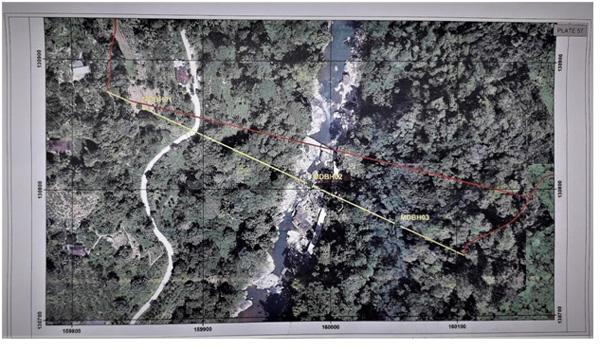

Environmentally, the most contentious issue highlighted in the news media is the proposed construction of a RCC dam at Madugeta to build a reservoir for which around 79 ha of forested (and some agricultural) lands in Sinharaja and a portion of prisine riverine forest in Dellawa would be inundated (figure 2). On the Sinharaja side of the proposed Madugeta reservoir (right abutment) at present there are home gardens and small-scale tea plantations in addition to good riverine forests. In contrast however, proportionately a larger area of luxuriant forest of Dellawa, which is a part of the new ‘Sinharaja Rain Forest Complex’ would go under the chain saw for this reservoir construction (left abutment). The Geo-engineering report of May 2019 on GNDP has revised the siting of the dam to a more favorable location with supposedly reduced impacts but they forewarn that the three core-drilling along the proposed dam axis that had to be temporarily abandoned due to protests made by the villagers, need to be completed to confirm the geological suitability of the proposed dam site.

Figure 2. A Drone image of the proposed Madugeta Reservoir site with its dam axis (in yellow), Dellawa forest -a part of the Sinharaja Rain Forest Complex (right of Gin Ganga in this image orientation). Tea gardens and villages on the Sinharaja side (left of Gin Ganga)

Are there any Environment -friendly Alternative Options?

As an alternative site for a dam on Gin Ganga, Eng. Nandasoma Atukorale (Specialist Engineer [Hydropower]) has proposed a location at the confluence of Mahadola with Gin Ganga at the village of Mederipitiya, way back in 2006. According to him, the riverbed at this site is 261 masl and have a catchment area of 132 km2. He proposes the construction of a 35 m high concrete gravity type dam that would form a reservoir with a storage capacity of 65 million cu.m and a potential discharge of 320 million cu.m of water annually which could divert 293 million cu. m of water to the SE Dry Zone. Most importantly, this region passes through a relatively narrow section of the river which is ideally suited for a dam according to him. However, geological suitability and socio-economic impacts of local communities need to be investigated, beforehand.

Quite interestingly, Eng. Athukorale claims that ‘although it is not economically very attractive, another 200 million cu.m of water could be diverted to the Nilwala basin by constructing a dam across Gin Ganga at the downstream of the confluence with Dellawa Dola at the village of Madugeta, with an 8000 m long tunnel which could be considered at a later stage provided further water shortages are experienced in the area’.

Now that the proposed Madugeta reservoir is receiving heavy criticisms from the environmental front, wonder whether Mederipitiya option proposed by Eng. Athukorale could be revisited for the diversion of Gin-Nilwala river water to the SE Dry Zone.

In a research paper titled ‘Comparison of Alternative Proposals for Domestic and Industrial Water Supply for Hambantota Industrial Development Zone’ Eng. Prema Hettiarachchi makes a comparison among three irrigation projects Kukule Ganga, Gin-Nilwala and Wey Ganga to convey water from the SW wet zone to SE dry zone. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344179735_Comparison_of_Alternative_Proposals_for_Domestic_and_Industrial_Water_Supply_for_Hambantota_Industrial_Development_Zone)

She proposes yet another option that is probably still on the drawing boards to be considered which is the Wey Ganga diversion in Ratnapura District. According to her, this could meet the industrial and drinking water requirement (154 MCM + drinking water) of Hambantota metropolitan area at a significantly lower cost and with less damage to the environment. Further, there is a possibility of augmenting this scheme by diverting a part of Kalu Ganga catchment at a later stage.

Eng. Hettiarachchi further states that ‘by comparing the workload, it could be estimated to be nearly one third that of the Gin-Nilwala diversion. The Wey Ganga diversion can be carried out at a significantly lower cost by local agencies. That can also address the water scarcity of Hambantota metropolitan area including the requirements of international harbour and proposed industrial development zone with the relatively less environmental damage which is a major issue with respect to large scale projects. Construction period will also be less since the workload is less and can be carried out by the local agencies.’

What I have strived to show with this detailed irrigation engineering information available on public domain in the form of research publications, is that the Madugeta reservoir option is not the only one available for taking water from the wet zone rivers to the SE Dry Zone which is indeed a legitimate requirement for agricultural and industrial development of that region.

Pre-feasibility studies have been conducted on these options since 1968 and a considerable wealth of technical information is already available with the Irrigation Department. Apparently, according to knowledgeable irrigation engineers, there are more environmentally friendly, and cost-effective options with greater assurance of water conveyance to the SE Dry Zone available for consideration. It is often the case that during pre-feasibility studies of these large engineering projects, environmental concerns are given the least priority. Steady flow of water during extreme drought events which are becoming more frequent depends very much on the nature of the vegetation cover of the watershed area. These environmental aspects need to be critically evaluated before such costly projects are designed. As an example, although, the major engineering work of the Uma Oya project has been almost completed, its cost-effectiveness is yet to be seen with a denuded watershed, a potential of heavy soil erosion on top of the unexpected heavy expenditure on tunnel boring and other engineering works.

Biologically speaking, Dellawa Forest Reserve is an integral part of Sinharaja Rain Forest Complex representing the pristine climax forest vegetation of SE wet lowlands and provide a vital connectivity link to adjoining Diyadawa forest of equal significance via the remains of Dombagoda forest. Therefore, clearing a riverine strip of this forest for the construction of Madugeta Reservoir would lead to an irreparable and irreplaceable damage to its characteristic riverine/flood plain forest vegetation.

On the other hand, pledging a reforestation initiative of a much larger area with Hevea rubber as a compensatory measure proposed by the political administration is totally unacceptable. Preserving intact forests in protected areas has no substitutes or replacements. Furthermore, the Natural Heritage Wilderness Area act and the binding articles of the UNESCO Convention on Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage to which Sri Lanka is a signatory, clearly state that causing direct or indirect damage to a natural heritage is legally not permissible.

In summary, the Sinharaja World Heritage Site is already in a state whose biological values are threatened and/or are showing signs of deterioration and significant additional conservation measures have been recommended to restore these values over the medium and long term. Adding more threats like the construction of reservoirs inside protected areas at this stage would inevitably downgrade the values further to a ‘critical conservation outlook’ which is not what the citizenry of Sri Lanka and the world at large would acknowledge as ‘sustainable development’.

(The author of this article extends his thanks to Dr. Jagath Gunathilake of University of Peradeniya for the geo-technical information described herein. The author is a member of the National Sustainable Development Council of Sri Lanka and can be contacted at nimsavg@gmail.com.)

Leave Comments