By Rajan Hoole

In writing for a major anniversary of our school, we affirm its greatness, the good times we had, the eccentricities of the teachers who acted for our own good, the scenery and environment that stay etched in memory; and the achievements of fellow students who made their mark in the world. In the memory of a little boy in the age of innocence, I am awed by the beams of sunlight pouring through the foliage of tall mahoganies that seemed to reach up to the sky. It symbolised the greatness of the institution we were part of. In remembering and reaffirming this in the company of old students from all parts of the wide world, we assure ourselves of our place in it and it is no mean corner of it that is ours. I indulged in such thoughts when I wrote 25 years ago, but that seems out of place against present reality.

I now write as one of the exceptions in my class, whether at Chundikuli or St. John’s, that actually lives in Jaffna. Many people in this country, in view of the past tragic decades have decided this is not the place for their children. Being at the tail end of the Psalmist’s life span, I see very few of my old mates. A number of them came to Jaffna after the war ended to reclaim their properties, smiled, exchanged pleasantries with old friends, or thanked those who had protected their belongings and said their last goodbyes after getting the best prices for their land, often to the detriment of those left behind.

Many would claim that they had no alternative, but there should be no pretence that they left behind a healthy society and schools, and share no responsibility for the fate of a people who were their neighbours for generations. On the surface things could appear normal, but behind it lurks loneliness, absence of civic sense, coupled with a fear of going beyond personal interest and standing up for what one believes is right and decent.

It has a debilitating effect on education. Another writer in this series has referred to my mother Jeevamany Somasundaram, an old girl of Chudikuli who sat for her Cambridge Senior (O Levels) about 1934. A story that moved me deeply was related by my piano teacher Miss Abbey Hunt. She said that during lunch intervals, when the girls were amusing themselves with various pursuits, my mother sat beneath a mahogany tree, working riders in Euclidian Geometry. It was an injunction setting a standard: once you take a problem in hand, think it through to the end. It is not a story about one woman, but about a school, an atmosphere, the teachers and their personal interest that challenged students to a high level of intellectual rigor.

Until about the 1970s several schools in Jaffna had teachers who identified capable students and took a keen interest in their future. A student of my age at Hartley told me that his Mathematics teacher, R.M. Gunaratnam, once caught him in a vice-like grip in Pt. Pedro town and warned him about his absence from classes. Today that link between teachers and students has greatly diminished, and teaching has largely been sub-contracted to tutories. It has led to a marked fall in intellectual standards and the near disappearance of intellectual life in Jaffna.

Tutories are not about teaching students to think, but produce good grades in A’ Levels. My experience in university teaching too has been that few students attempt tutorial questions, but wait for answers to be given in class. It has resulted in a culture of not wanting to think through a problem. The university training amounts to teaching people to apply formulae and get results, and not bother with foundations. Many of them emigrate and get jobs abroad, which makes me suspect that we are good at producing engineer-clerks and doctor-clerks who perform their routines quite well.

Leaving behind a desert

I have referred to the ongoing sale of expatriate properties in Jaffna, which are followed by the capricious appearance of high rise buildings and the disappearance of tanks and drains. Common sense points to danger. The most damning indicator was the flooding of Jaffna Hospital during the last rains when medical staff and patients were knee-deep in water.

Coming to the issue of thinking a problem through to the end, the building spree in Jaffna has been promoted by persons in authority promising modernised water, drainage and sewage systems for Jaffna. When there is prospect of huge foreign loans, perks and contracts, basic constraints are swept under the carpet. Foreign experts are all for it and, and of our own experts who sold it, few will ultimately be rooted in Jaffna. Novel possibilities were talked about for many years and dropped; such as desalination in Vadamaratchi East, water from Iranamadu Tank for Jaffna only in flood years, or finding new sources, all of which showed that something was wrong at the root of the idea. I must digress a little.

Iranamadu has an average inflow of 147 MCM (Mega Cubic Metres), adequate for cultivation of 95 per cent of paddy in Winter and 30 per cent in Summer (World Bank, 1984). Supplying Jaffna means pinching 10 MCM of inflow to be piped out. A very basic constraint can be worked out from variations in river flow studied by older professionals like R. Sakthivadivel. The studies which are available on the web have been ignored. I worked out in my book Palmyra Fallen (2015) commemorating Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, that the 75 per cent reliable flow into Iranamadu is 80 MCM. Nature has a cycle of about four years, and once in those four years (25 per cent of the time), you could get 80 MCM or less, even though the average is 147 MCM.

In such lean years sending 10 MCM to Jaffna would be very hard on the local farmer. There are years of severe flooding but that excess has to be allowed to run to the sea. That is the short explanation of the problem. Funds were rolled out, pipes were sunk and holding towers were built. Going by press reports the matter has been at standstill from before January 13, 2019 (Sunday Observer), against protests in Killinochchi.

Although we had some of Jaffna’s leading professionals on the job, they did not think the problem through. They simply defined the problem as water being available at Iranamadu (the average inflow) and laying the works for piping it to Jaffna. The cyclical variations of river flow (Kanagarayan Aru) were simply ignored by those who should have known best.

The problem comes down to present-day Jaffna lacking an educated critical mass with the motivation, ability and connections to look after their basic interests like a clean environment and drinking water. Those with money and power have their interests elsewhere. The problems faced by many residents in Jaffna are not dissimilar to those of civilians in Rathupaswala, Gampaha, three of whom were killed on 1st August 2013 over their protest for clean drinking water.

One Jaffna family saw a hotel and a high rise building coming up on the lands of well-to-do former neighbours, which they had looked after during the war. Prices offered from black money were what their left-behind neighbours could not match. The well water in the area remains undrinkable or murky in addition to noise pollution. In the absence of a sewage system they do not know how human waste is being disposed of. Excessive drawing of water from one urban well could cause others in the neighbourhood to run dry.

Black money came, according to the well informed grapevine, in post war years from funds connected to the departing rulers held by selected businessmen. In time this black money made connections to political and similar funds in the South and in an unhealthy way fills the present gap our once independent institutions are unable to fill, particularly in health and education.

The Church that sustained Jaffna’s premier institutions in education and health fell victim to emigration and division. There is no local vision or qualified presence in Jaffna to sustain the education up to tertiary level and the medical network it pioneered. Money-centred education and medicine have thrown up a class of nouveau riche, whose impact could be classed along with that of black money.

Absence of a civic voice for Jaffna

Dr. Rajani Thiranagama

Between Chundikuli and St. John’s, it was C.E. Anandarajah who, as principal, stood forthright as a leading voice of civil concerns in Jaffna until he was killed by the LTTE in 1985. I see the two schools as having remained timid on social concerns since. Chundikuli produced in Dr. Rajani Thiranagama a rare voice of defiance, courage and compassion, whom I was close to in the path-breaking finale of her activism ending with her assassination by the LTTE in 1989. Her civic sense as a doctor led her to treat an LTTE injured when no one else could be found. She then became involved with the LTTE. Having then become disgusted with its inhumanity, she stood up and challenged it in Jaffna itself out of compassion for those it was destroying. What she was up against is illustrated by elite politics in a society that still extols an ideology; one that in its last stand in 2009 held hostage 300,000 civilians under fire, in order to strike a deal for the safety of its leaders.

I began with the importance of educational training that urges one to spare no effort in thinking a problem through. It applies equally to the state of our politics. There was no strong resistance in Jaffna society when G.G. Ponnambalam, who was our leader in 1948, cooperated with Prime Minister Senanayake in nullifying the rights of Up Country Tamils. Ponnambalam was only following the line of several notables from the North; many of them not his supporters (A.J. Wilson, Political Biography of Chelvanayakam). The damage we did to the Up Country Tamils hurt us grievously in the long term. Since then we have been crying over spilt milk – the large numbers of dead and the exile of our brightest and best to Austroeuramerica.

Our fragmentation and growing isolation is reflected in queries about how the dowry of a bride from Jaffna would translate into real estate in Colombo or Sydney. We cannot stop at observing that we have been poorly served by most of those who left us. The present girls of Chundikuli have as much talent as there was in the time of our mothers and aunts. What they need is to rediscover the tradition that questions everything they are told and reason them out to the end. I don’t think I am wrong when I say that what made Jaffna great in the 1930s and 1940s was the strong surge of sympathy for the Indian independence struggle. That was when the influence of Gandhi and liberated women like Kamaladevi Chattopadyaya and Sarojini Naidu, all of whom came to Jaffna, made a tremendous impact on its people.

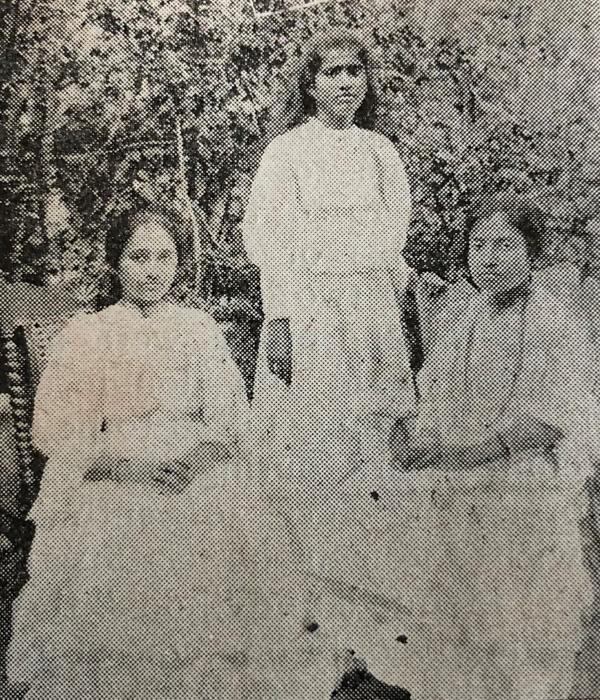

Sisters and beloved teachers: Kanaham and Yogam Muthiah

My mother spoke of her teachers with great affection. When she was on the staff of the school and was engaged in 1947, the Principal Dr. Miss. Evangeline Thilliayampalam (PhD Columbia, 1929, aged 34) counselled her that an engagement should not be prolonged. Her Jubilee message in 1946 points to a woman who was silently politicised: “The forces which retard human progress are poverty, ignorance and class rivalry.” My mother also spoke fondly of the Muthiah sisters, Kanaham and Yogam. I quote from Lorna Vandendriesen who said in a tribute to three Chundikuli teachers, ‘who really set high standards and ran the school regardless of who was the Principal. Gracious Miss. Grace Hensman, gentle Miss. Kanaham Muthiah and beautiful Miss. Yogam. They were wonderful teachers. I know. I was their pupil.’

I.P. Thurairatnam, who was later principal of Union College, said that he won the ‘Mixed Doubles Championship with Yogam Muthiah of Chundikuli. Spurred by these victories we tried our mettle at the All Ceylon Tennis Meet in Nuwara Eliya in 1932 and 1933, and met with moderate success.’ Chundikuli girls long had a reputation as trendsetters.

I may add that admitted to Chundikuli as a boy of seven I spent two golden years as a novice to the world of the fairer sex (1956/7). I too was pleasantly affected by my charming class teachers Miss. Jeevaratnam (now Mrs. Yogaratnam) and Miss. Champion (later Mrs. Ponniah).

Favourite teachers: Jeevu Champion nee Hitchcock, Nesamalar Yogaratnam nee Seevaratnam and Agnes Ponniah nee Champion

Today’s Jaffna could be a very discouraging place. In order to sharpen our analytical ability and think problems through without resting satisfied with half-baked solutions we need public discussion, friends and colleagues who would tell us bluntly when we are being asinine. When we become defensive and take offence at criticism, even a well-endowed institution like a university would fail to prepare students to think through problems and aspire to a just society, while the teachers themselves remain frogs-in-the-well.

We cannot change things overnight, but what well-wishers could do for schools like Chundikuli is to expose students to speakers who will encourage them to question everything. This we used to have in the 1950s and 1960s when visitors from India were frequent. It also means reversing swabasha isolationism.

Tennis champs 1908: Lily Ramalingam, Jeevamanie Joseph and Yogam Muthiah

Chundikuli’s Grace Hensman Memorial Hall

Leave Comments