By Dr. Y Ratnayake, former Director of Planning, Industrial Development Board (IDB)

The economic status of any country, developed, developing or underdeveloped, is determined by the contributions made to the country’s GDP by the different subsectors of the economy, among which the SMI (Small and Medium Enterprises) sector is recognised as a significant contributor due to its ability to create multidimensional advantages in contrast to the benefits generated by large industrial enterprises.

Empirical data relating to the performance of the SMI sector in different countries as well as theoretical explanations on the same provide unequivocal evidence that SMEs are capable of creating employment at low capital costs, minimising the disparity in income distribution, alleviating the magnitude of poverty, and establishing a self-regulated economic mechanism that mitigates the government's responsibility in general in its role as the source of provider to society.

Landscape of SMEs in Sri Lanka

The genesis of SMEs in Sri Lanka may be traced back to long years of evolution, and the sector existed as an informal entity operated by interested individuals who were never brought into the limelight or promoted by the administrative regimes that governed the country from time to time. However, the significant role that the SMI could perform in the economy was increasingly recognised with the changes in the political landscape, particularly commencing from 1956 and further accelerating in 1977, which resulted in the establishment of administrative and policy structures under the aegis of the Ministry of Small Industries.

A meta-analysis of time series data pertaining to SMI in Sri Lanka provides a picture of a skewed distribution of small enterprises with a heavy concentration of a large number of units in agriculture proper or further processing of agricultural products with geographical scattering in all administrative districts of the country. Apart from agriculture, the other dominant economic sub-sectors in which SMEs are actively engaged include light engineering, service sectors, fishing and animal rearing, restaurants, retailing, and groceries. According to the available data in the public domain, the enterprises falling into the pertinent sectors can again be subdivided on the basis of formal and informal enterprises based on the current status of whether they are registered with any of the government institutions coming under the three administrative hierarchies, namely central, provincial, or local.

A large number of SMEs are supposed to be operating without any formal registration and are therefore being classified as informal business entities. Informal enterprises are sometimes referred to in disparaging terms as dirty SMEs due to ubiquitous business traits possessed by them such as unethical practices, lack of business vision, unscrupulous greed for quick profits, and deceitfulness, which are general characteristics of business myopia, an infection that destroys a business from within. Furthermore, the nomenclature used by policymakers and academic writers seldom distinguishes the differences in the terminology such as SMIs, SMEs, micro-enterprises, cottage industries, family business etc. which are characterised by hereditary variations from one another in relation to management style, financing, magnitude of operation scale, production technology and business turnover.

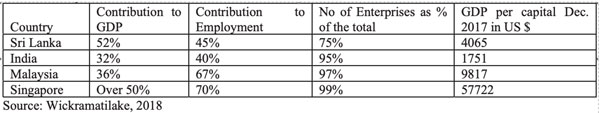

As remarked by the Asian Development Bank, SMEs are the bedrock of Sri Lanka’s economy, accounting for 75 percent of the total number of enterprises active in the country, providing 45 percent of employment, and contributing 52 percent to its gross domestic product (GDP). However, contrary to the various affirmative statements made by different sources, the performance and position of the SMEs in contrast to other neighbouring countries in Asia do not appear to be impressive in all the other major performance atmospheres except the contribution to the GDP.

Contrast with Southeast Asia

For the purpose of contrast, reference is made to the study report published by the Asian Development Bank, which reveals that MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) in Southeast Asia accounted for an average of 97.2 percent of all enterprises, 69.4 percent of the total workforce, and 41.1 percent of a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) during 2010–2019. The share of MSMEs in total enterprises slightly declined across the region, dropping at a compound annual rate of 0.3 percent. Meanwhile, the share of MSME employees in total employees rose by 0.8 percent, and MSMEs’ contribution to GDP expanded by 2.3 percent at a compound annual rate. During 2010–2018, MSMEs contributed 20.4 percent of a country’s export value on average (a compound annual decline of 0.05 percent).

Table

Comparative Data on MSMEs in Selected countries.

Clutter of Definitions and Policy Frame Jungle:

Definitions on any subject or operational function are construed as a sin qua non in relation to any rational undertaking since such definitions help build the relevant boundary parameters of any subject. In fact, the subject of SMI has been considered, from its very inception, a weird concept due to the clutter of definitions made available not only in Sri Lanka but also internationally by different subject-specific agencies. Concerning the Sri Lankan situation, different SME promotional agencies, which are in fact proliferated in the public sector, have applied their organisation specific eligibility criteria for the selection of SMEs that are qualified to receive extension facilities such as finance, and technology, under their promotional programmes.

The governmental organisations playing dominant roles in the promotion of SMEs in Sri Lanka are, inter alia, the Industrial Development Board of Sri Lanka, the Export Development Board, the Department of Small Industries, and the Youth Council. They have carved out their own respective share of the SME sector with due emphasis on their sphere of operation as specified by the related acts of incorporation. In addition to the SME definitions given by the above organisations, the Central Bank, the Ministry of Policy Planning, and most of the commercial banks have come out with their own definitions, which creates a definition jungle that confuses the logical-minded observer due to the ambiguous conceptual frame characterised by gaping variations and blurred visionary direction.

All the Businessmen are Not Entrepreneurs

As the well-known management sage Peter Drucker states, all businessmen are not entrepreneurs since many businessmen, a large percentage for that matter, lack the entrepreneurial traits and ethos that have been associated with the successful entrepreneurs who proved their business acumen in building business empires through innovation and unwavering hard work. In the context of many SMEs in Sri Lanka, the focal driving force that propelled many investors into starting businesses is related to non-entrepreneurial goals created by the need for economic circumstances. Nonavailability of a stable income-earning source, government assistance programmes that made SMSs lucrative, or the sudden impulse to imitate the business project that they have come across have been cited as the main factors that propelled a significant percentage of investors in Sri Lanka to enter the SME sector. This phenomenon is not confined only to Sri Lanka, as information available in the public domain proves that similar trends have been reported with axiomatic evidence in many other countries in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

According to a recent report published by the US Census, approximately 2,356 Americans are becoming entrepreneurs by starting new businesses every day. Furthermore, according to a 2006 report from North-Eastern University's School of Technological Entrepreneurship, 62 percent of entrepreneurs in the US claim that innate drive is the number one motivator in starting their business, which, in other words, means that 38 percent of investors are still driven by nonentrepreneurial motives.

The rate of business failure among SMEs in Sri Lanka is 45 percent, and, according to statistics published by the Small Business Administration (SBA), at least 30 percent of new establishments fail within the first two years from their inception, while 49 percent fail within five years.

Factors Attributing to SME Failure in Sri Lanka: Non-entrepreneurial Orientation

SMEs in Sri Lanka have reported a high failure rate, though somewhat similar to that experienced by many other countries. Close scrutiny of meta-studies and diagnostic reviews of SMEs on a case-by-case basis indicate that a complex web of interconnected factors has contributed to the majority of SME failures across the board. Many SMEs in Sri Lanka are largely established due to non-entrepreneurial propulsion, which in fact affects the vibrancy of the business from negative perspectives, resembling the scenario that a living being can be deformed at birth due to weaknesses transferred through the molecular structure of chromosomes. Such enterprises started with the wrong establishment motive are doomed to experience high fatalities and premature collapse, like a building constructed on a foundation that is not well compacted and reinforced.

Entrepreneurial traits that propel a person to mobilise oneself into business investment essentially consist of a blend of special talents such as creativity, innovation, perseverance, business acumen, and craving for success that largely contribute to the vigour, vibrancy, and wholesome future growth of an enterprise in the future. As Peter Drucker correctly articulates in global terms, many SME owners in Sri Lanka have gravitated into business by the sheer compulsion arising from, inter alia, unemployment, lack of income, a sudden impulse for imitation (me too business motive) of what they have come across, and so on, which can be considered nonentrepreneurial of orientation, a sure recipe for future failure.

The wrong orientation leads to many other malaises, among which business myopia, a term introduced by T. Levitt, constructs a destructive barrier that incapacitates the investor from distinguishing the difference between his long-term goals and the operational targets of the enterprise. This situation is very frequently demonstrated by high pricing strategies, customer exploitation, unethical trading practices, zero sensitivity to quality control, high-handed attitude towards the customer etc. which are all pertinent factors that contribute to the reduced life span for many SMEs.

Incubated Entrepreneurship

Under the aegis of GOSL, a number of SME promotional agencies and commercial banks are engaged in providing financial assistance as well as numerous extension services to potential businessmen, but the pertinent issue involved is the degree of uncertainty prevailing on the capacity of such assistance programmes to identify talented entrepreneurs in the first instance and then to ensure their continuous engagement and steady growth as anticipated by the policy formulators.

The sponsored entrepreneurship development promoted under the aegis of the government may be contrasted with the forcible conscription of youths to the armed forces of a country, which does not necessarily vouch for the development of an energetic solder once his training comes to an end. As some critics point out, the incubation of entrepreneurship under the spoon-feeding programmes launched by government agencies leads to the creation of hybrid SMEs whose survival hinges upon the uninterrupted backup channelled by the promotional agencies in the forms of financial concessions, low-cost supply of raw materials, government-sponsored marketing, tariff protection, etc., which poses the question of the economic rationale for maintaining such SMEs. The exercise very often ends in futility since successful entrepreneurship springs, as local and international experience vindicates, from the internal motivation of individuals and their entrepreneurship-tailored personality traits.

Juvenile Marketing Approach

Even the preliminary precepts of marketing emphasise that marketing starts before the commencement of production so that the entrepreneur is thoroughly conversant on the needs and wants of the customer that his business intends to satisfy or fulfil. However, a review of the meta-literature on the subject indicates that SME investors very often possess scanty or inaccurate knowledge of the market segment that they intend to cater to, which subsequently produces waves of negative ripple effects in different forms, penetrating all functional areas of the SME.

Single-track strategy

The most glaring shortcoming of SMEs that accelerates their premature downfall is the lacklustre business planning performed within the enterprise due to the paucity of business acumen and talents possessed by the investors, which leads to the obvious situation of the business drifting like a rudderless ship that short circuits its survival due to shipwreck no sooner than it is launched. A large majority of SMEs, since they are driven by a quick profit motive, envision a single-track strategy that is founded on price increases while paying scant attention to the self-destructive impacts that might follow subsequentially if the demand for the related product or service is highly price sensitive. In particular, the gig business totally thrives on the opportunistic high-price strategy that leads to the ruthless exploitation of customers while offering substandard or shoddy products and services to gullible buyers.

Glaring Negligence of Cashflow

It is often believed and publicly stated that the major contributing factor to the downfall of SMEs is the shortage of financial capital; however, a close analysis of the factors attributing to the untimely decay of SMEs proves that the aforesaid popular belief cannot be vindicated in the face of empirical evidence available with the related documentation. Financial crunch and shortages are the combined outcomes that wedge the smooth flow of funds, mainly the inflow, which results from the overall mismanagement of SMEs vis-à-vis production, marketing, customer care, and cash handling. Signs of poor cash flow management very often appear in the form of large inventory, wasteful initial capital investment, poor debt collection, overdue payments, payroll delays, overdue bank loan payments, and so forth, which obviously squeeze the inflow while the outflow remains either constant or swelling and expanding. The disastrous impacts of poor cash flow management have been comprehensively explained by Richard Kiyosaki (R. T., 1917) in his publication titled “Rich Dad and Poor Dad.”

Conclusion

The high fatality rate of SMEs in Sri Lanka, according to the perception of many, is due to the arduous accessibility to finance by the SMEs, but this assumed cause-and-effect relationship is hardly ratified by the ground reality related to actual reasons that cause a high rate of SME failures. Financial constraints represent only the tip of the iceberg, which not only conceals the actual problem but also misleads the observer to reach an erroneous adjudication. Poor functional management skills possessed by the SME investors spearheaded by the non-entrepreneurial orientations are the main culprits for the untimely succumbing of SMEs in Sri Lanka.

Leave Comments